This post is also available in: Bosnian

In May this year, Novak Stjepanovic posted on Facebook a photo of himself in a forest, a rifle on his shoulder, in military uniform bearing the words ‘Armed Forces of Russia’.

“Destined by God to fight for justice all my life,” he wrote.

Roughly a dozen photos and posts, by 59-year-old Stjepanovic and others, place him in Russian-occupied Donetsk, eastern Ukraine, between April and June, despite a court in Belgrade having convicted Stjepanovic in December last year of war crimes against civilians near the Bosnian town of Bratunac in 1992, crimes that included complicity in murder, torture, rape, inhumane treatment and theft.

In June, the month after Stjepanovic posted his ‘fight for justice’ photo, the verdict was confirmed, and he was sentenced to 13 years in prison. Stjepanovic’s precise whereabouts are not known, but it is highly likely he is still in Ukraine, fighting with Russian forces that invaded the country in early 2022.

The Higher Court in Belgrade confirmed that, during the trial, Stjepanovic was not prohibited from leaving Serbia.

He was present when the verdict was read out in December, but Jovana Kolaric, who followed the trial as a researcher at the Belgrade-based Humanitarian Law Centre, said individuals sentenced to jail in Serbia are not usually put behind bars immediately.

“The problem is that all of them are defending themselves while at liberty; detention measures are very rarely ordered,” Kolaric told BIRN. “They are mostly reserved for persons who are not citizens of Serbia.” Stjepanovic holds both Serbian and Bosnian citizenship.

Edina Karic, one of three women held captive by Stjepanovic and other Bosnian Serb soldiers early in the 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, said she had “lost all hope”.

During the trial, Karic testified that she witnessed Stjepanovic rape a 19-year-old woman.

“It’s a disaster,” she said of Stjepanovic’s ability to evade justice. “I don’t believe in the judicial system at all.”

Neither Stjepanovic nor his Belgrade-based lawyer responded to repeated requests for comment.

Crimes against civilians

Novak Stjepanovic (right) with another soldier and a vehicle with the licence plates of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, an unrecognised Serb-run statelet within Croatia during the 1991-95 war. Stjepanovic’s caption reads: “Back in the day we were young and healthy, but time takes its toll.” Photo: Novak Stjepanovic/Facebook

Stjepanovic was first indicted for war crimes by a court in Bosnia in 2009, two years after Bosnian authorities issued a warrant for his arrest. The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina charged him with the capture, abuse and murder of civilians in Bratunac.

It was only nine years later, however, that Bosnia managed to serve him with a new indictment, this time for sexual violence, while he was living in the Serbian town of Ljubovija, just over the border from Bratunac.

The two indictments were then merged and the case transferred to Serbia; Stjepanovic’s trial began in January 2021 at the Higher Court in Belgrade.

In December 2024, in a first instance ruling, Stjepanovic was found guilty and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The court found that, as a member of the Bosnian Serb army, Stjepanovic participated in capturing 14 Bosniak civilians in the village of Borkovac, near Bratunac, in May 1992, during a wave of brutal ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs in eastern Bosnia. The civilians were assaulted, robbed and forced to a nearby stream, where eight were killed. The court also found that Stjepanovic raped a 19-year-old Bosniak woman early the following month.

The Belgrade Court of Appeal confirmed the verdict in June this year but increased his sentence to 13 years.

Stjepanovic, however, was long gone. The last record of him appearing in court was on December 24 last year, when the first instance verdict was pronounced.

In a meantime, prosecutors in Bosnia opened a new investigation into Stjepanovic concerning the murder of six civilians in Bratunac during the war. The case was sent to Serbia, but prosecutors in Belgrade sent it back, saying certain documents were missing.

“After reviewing the files in the case, it was sent yet again to the Serbian judiciary on October 16, 2025, with the note that the allegedly missing documentation was already contained in the case file that had previously been handed over,” the Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina told BIRN.

‘Playing war’

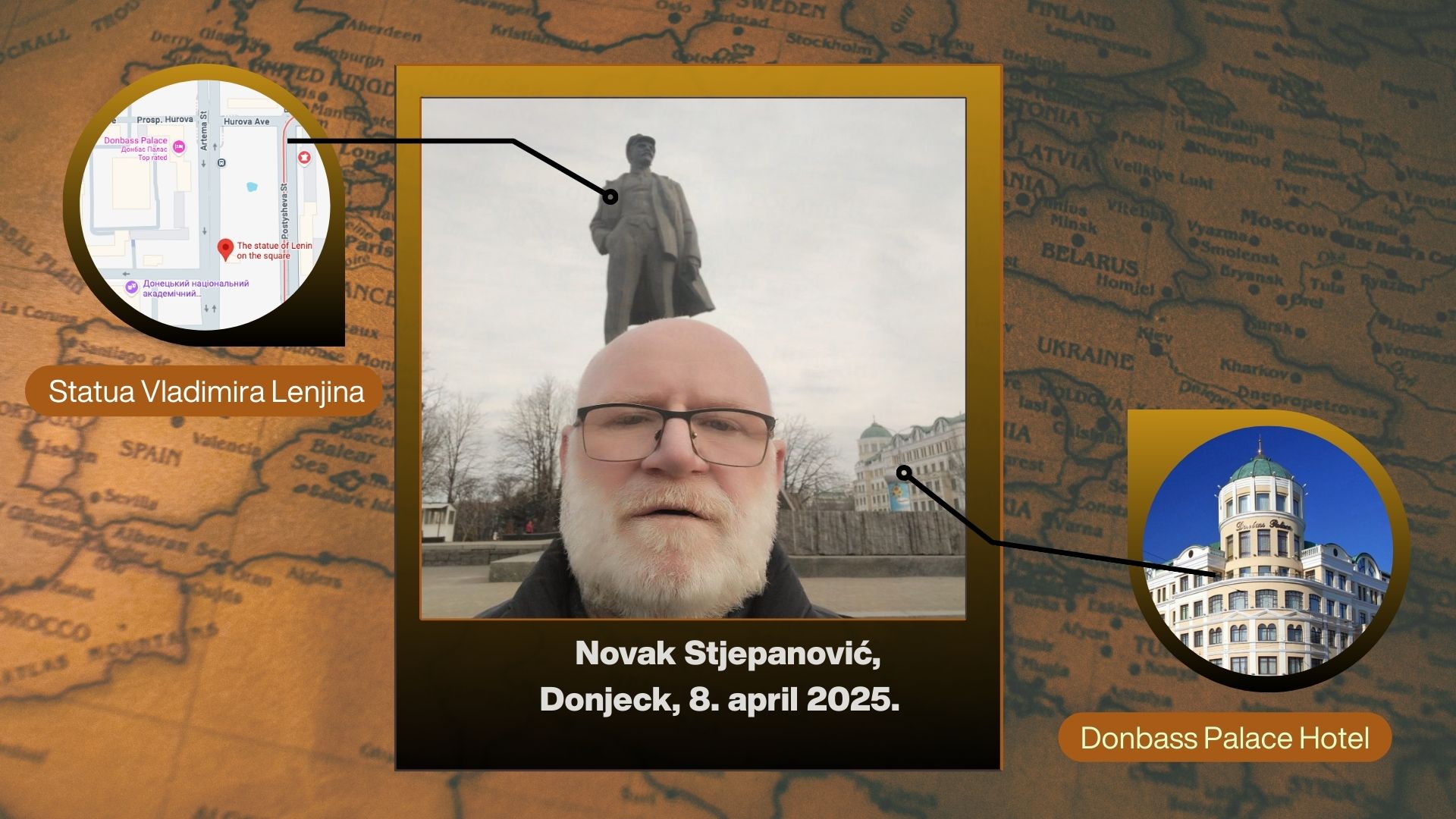

Stjepanovic’s location in the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk was identifiable from a photo he posted on Facebook. Photo: Novak Stjepanovic/Facebook. Illustration: Detektor

Stjepanovic first posted about travelling to Ukraine in early April, when he uploaded to Facebook a selfie in front of a statue of Vladimir Lenin near the Donbas Palace Hotel in Donetsk.

During April and May, he published 10 photos from Ukraine; one showed his military identification tags, commonly known as ‘dog tags’, engraved with a number and ‘ВС Россия’ – Armed Forces of Russia.

“I’m playing war a little bit in Russia,” he wrote in May in response to a question below a photo of him with an apparent wound to his right arm.

In May, a Bosnian Serb association of war veterans from Bijeljina, eastern Bosnia, published a photo of Stjepanovic during what it said was fighting around the village of Pokrovske, Donetsk region. The village was mentioned the same month by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who said the situation there was very difficult; Reuters news agency reported that elderly and sick residents were being evacuated.

The association told BIRN that the photo was taken from another Facebook page but did not name the profile.

Both Serbia and Stjepanovic’s native Bosnia revised their criminal codes in 2014 to prohibit participation in foreign conflicts, punishable by up to 10 years in prison in Serbia and eight years in Bosnia.

Nevertheless, media have regularly reported on mercenaries from the Balkans enlisting with Russian forces ever since Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and fomenting of rebellion in the eastern Ukrainian Donbas region, which Donetsk is part of.

Last year, the Ukrainian State Prosecutor’s Office requested information from Bosnia regarding 12 Bosnian citizens suspected of war crimes in Ukraine. The Prosecutor’s Office told BIRN it has yet to receive a response.