Between April and June 1993, Vrvilo was interrogated and beaten at the Music School, which had been turned into an unofficial wartime detention centre. He lost 19 kilogrammes while in captivity.

“Any word that did not suit them made them hit you on your back straight away,” he said.

He didn’t know the names of most of the military policemen who beat him up, except for one of them.

“He gave me quite a beating down there in the dining room once. His name is Nasid Delalic from Suhi Dol, near Han Bila,” Vrvilo recalled.

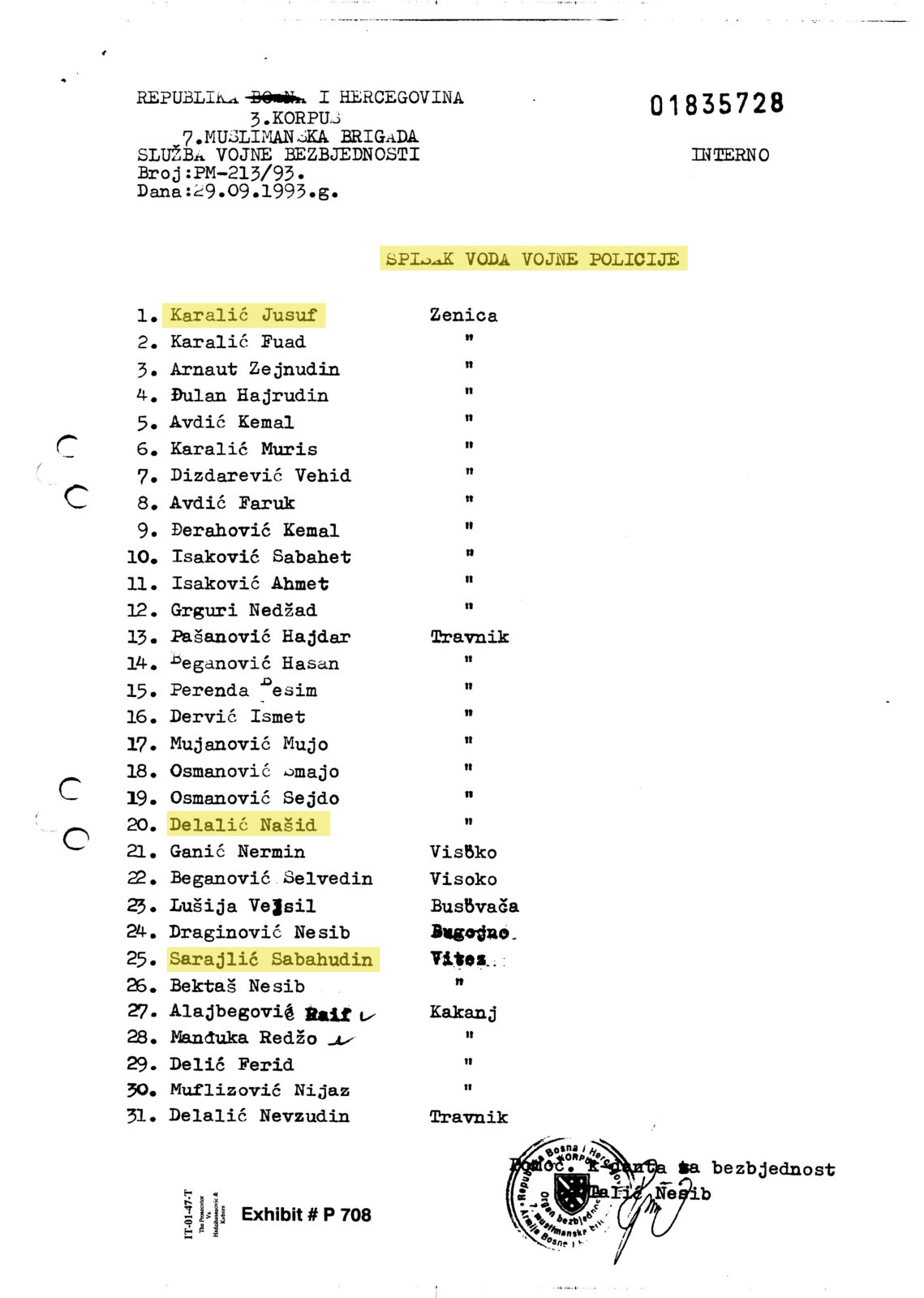

Delalic still lives in Suhi Dol, a village near the city of Travnik, with his family. He is one of at least five members of the Bosnian Army whose names are mentioned in the only verdict handed down by the Hague Tribunal that partially concerns the crimes against Croat and Serb detainees that were committed in the Music School in Zenica.

Delalic told BIRN that he never took part in interrogations of prisoners of his own free will, only “on someone’s command, if they called on me”. He said that “everyone got called upon – whoever was free”.

He said that he did not willingly participate in any violence against detainees: “I wasn’t involved in that of my own free will.” He also insisted that the detainees were not actually beaten up, although they were coerced to make statements.

However, in the detainees’ testimonies, they insisted that they were subjected to cruel treatment at the Music School.

According to testimonies at the trial of former Bosnian Army commanders Enver Hadzihasanovic and Amir Kubura in The Hague, soldiers and policemen used to play loud music in the building in order to muffle the cries and moans of prisoners who were being beaten.

Three decades have now passed since the crimes were committed at the Music School. Hadzihasanovic’s conviction established that he was guilty of having command responsibility for the crimes, but the direct perpetrators have never been prosecuted.

To find the names of potential suspects, BIRN analysed transcripts of witness testimonies, court documents and the verdict delivered by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, ICTY in the trial of Hadzihasanovic and Kubura, who were sentenced to three-and-a-half and two years in prison respectively.

All the prosecution witnesses’ testimonies in the trial concurred that they were cruelly treated on a regular basis and lived in an atmosphere of constant fear. Soldiers and guards would kick detainees and hit them with rubber cables and shovel handles immediately upon their arrival, and only then would they take them to the basement cell, covered in blood and bruises.

“We used to lie on pallets. There were three or four school desks, so some people also lay on them,” said Vrvilo. “We were not allowed to go to the toilet, but instead they would bring a five-litre plastic bucket, so we would use it and then someone had to take it upstairs. When it was my turn, I would be beaten up.”

‘I was black and blue’

One of the witnesses at the ICTY’s trial of Hadzihasanovic and Kubura was Kruno Rajic, who said that members of the 7th Muslim Brigade of the Bosnian Army brought him to the Zenica Music School on April 23, 1993.

Hadzihasanovic was the commander the Third Corps of the Bosnian Army Hadzihasanovic and Kubura was the commander of the 7th Muslim Brigade, which was part of the Third Corps.

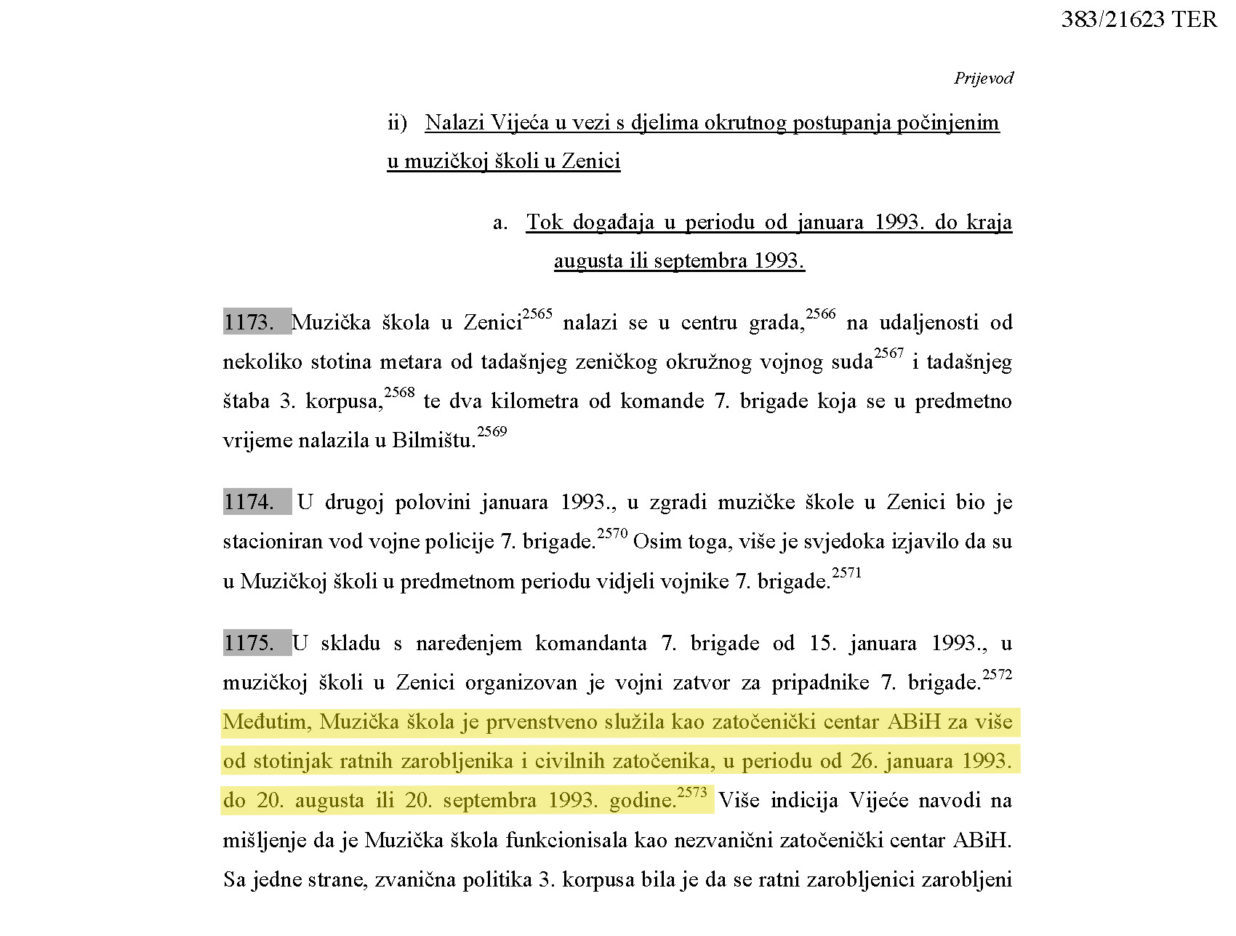

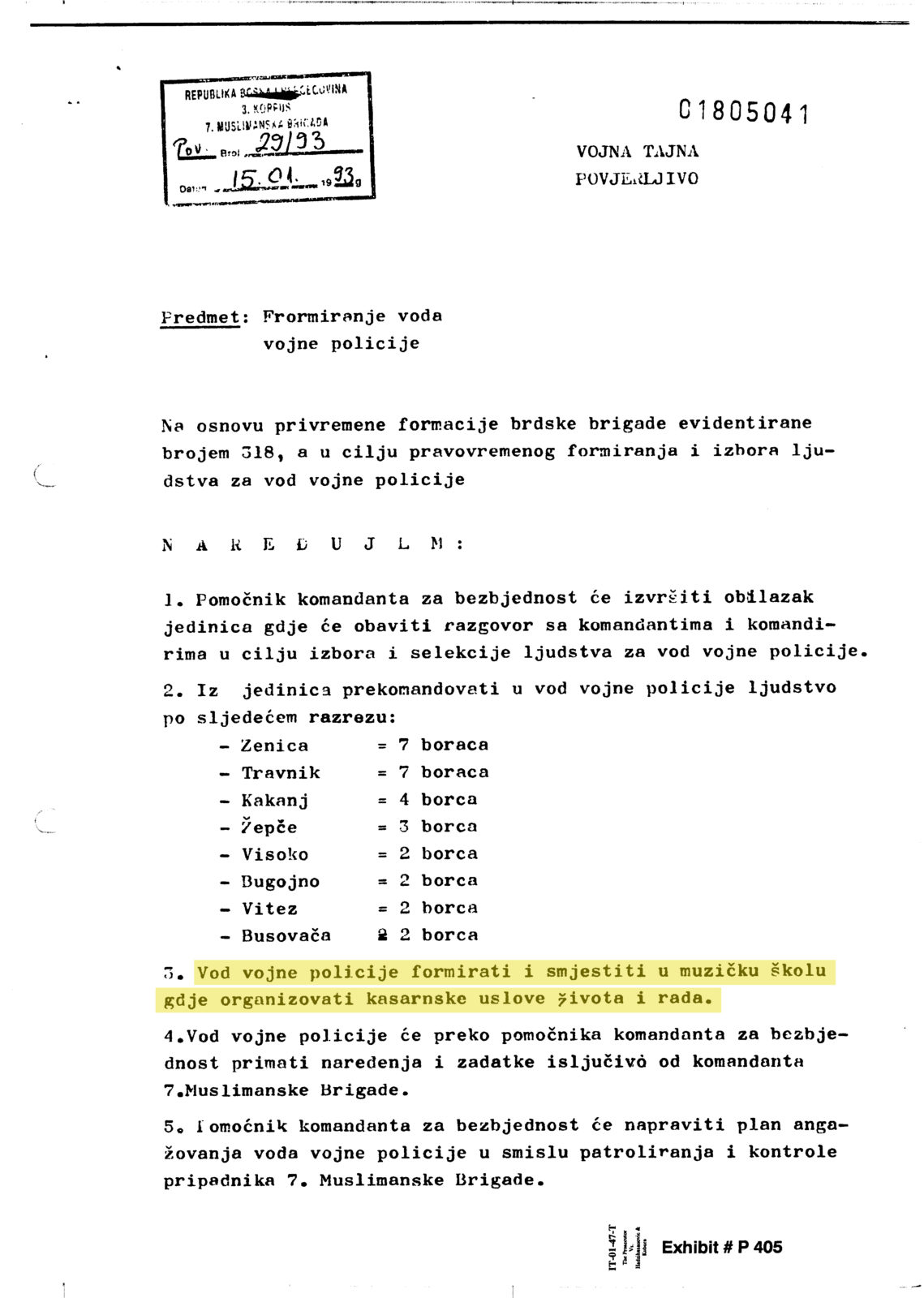

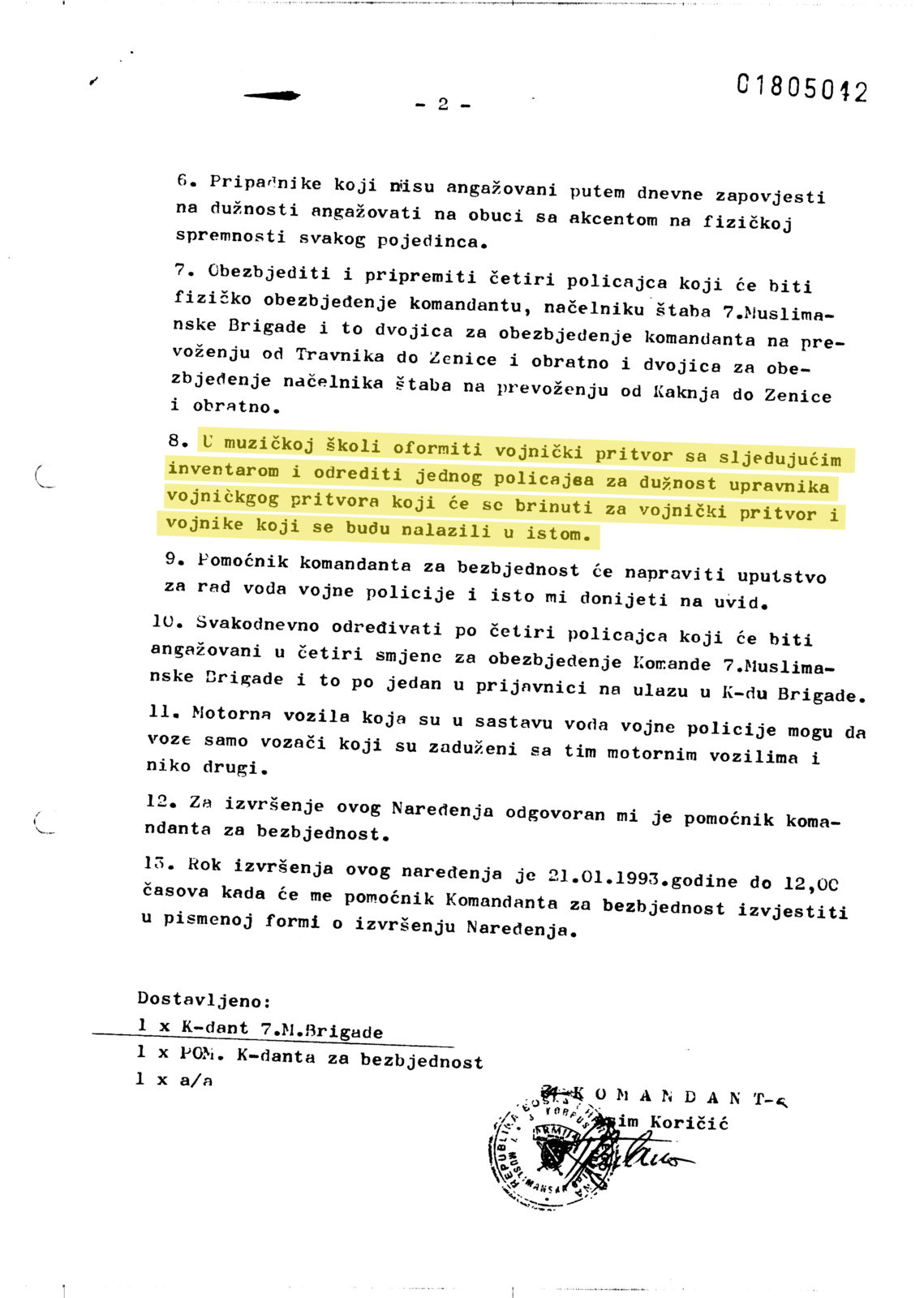

The verdict in their trial determined that the Zenica Music School was used as an unofficial detention centre by the Bosnian Army that held than 100 Croat and Serb prisoners of war and civilian prisoners in the period between January 26, 1993 and August 20 or September 20, 1993.

The verdict stated that in January 1993, around ten people were detained in the basement, and subsequently the number of detainees held there ranged from 15 to 46 in the period between the second half of April and August 1993.

Rajic said in his testimony that while he was detained at the Music School, both his arms were broken during the beatings he received, and he lost 30 kilogrammes in weight.

He told the Hague Tribunal that at one point he was taken from the basement where the prisoners were to a room on the second floor, where he saw Jasmin Isic, a guard who was a member of the 7th Muslim Brigade and who he knew from before the war.

When Rajic asked Isic what he was doing there, Isic told him they didn’t know each other, and the person standing behind Rajic hit him.

“He interrogated me. He asked me about a person known as Tarabica. I didn’t know what to say about that person. Each time he asked me something, I would say ‘I don’t know’, and the guy standing behind me would hit me,” said Rajic.

On his return to the basement, he was beaten by about ten policemen with cables and shovel handles.

“I was black and blue. My nose was broken. I was bleeding. I protected my head, I kept my hands on my head to protect my head while they were hitting me on my face and back,” he said. He added that he was interrogated and then beaten several more times.

Podrum Muzičke škole u Zenici. Foto: MKSJ

Podrum Muzičke škole u Zenici. Foto: MKSJ

Podrum Muzičke škole u Zenici. Foto: MKSJ

Podrum Muzičke škole u Zenici. Foto: MKSJ

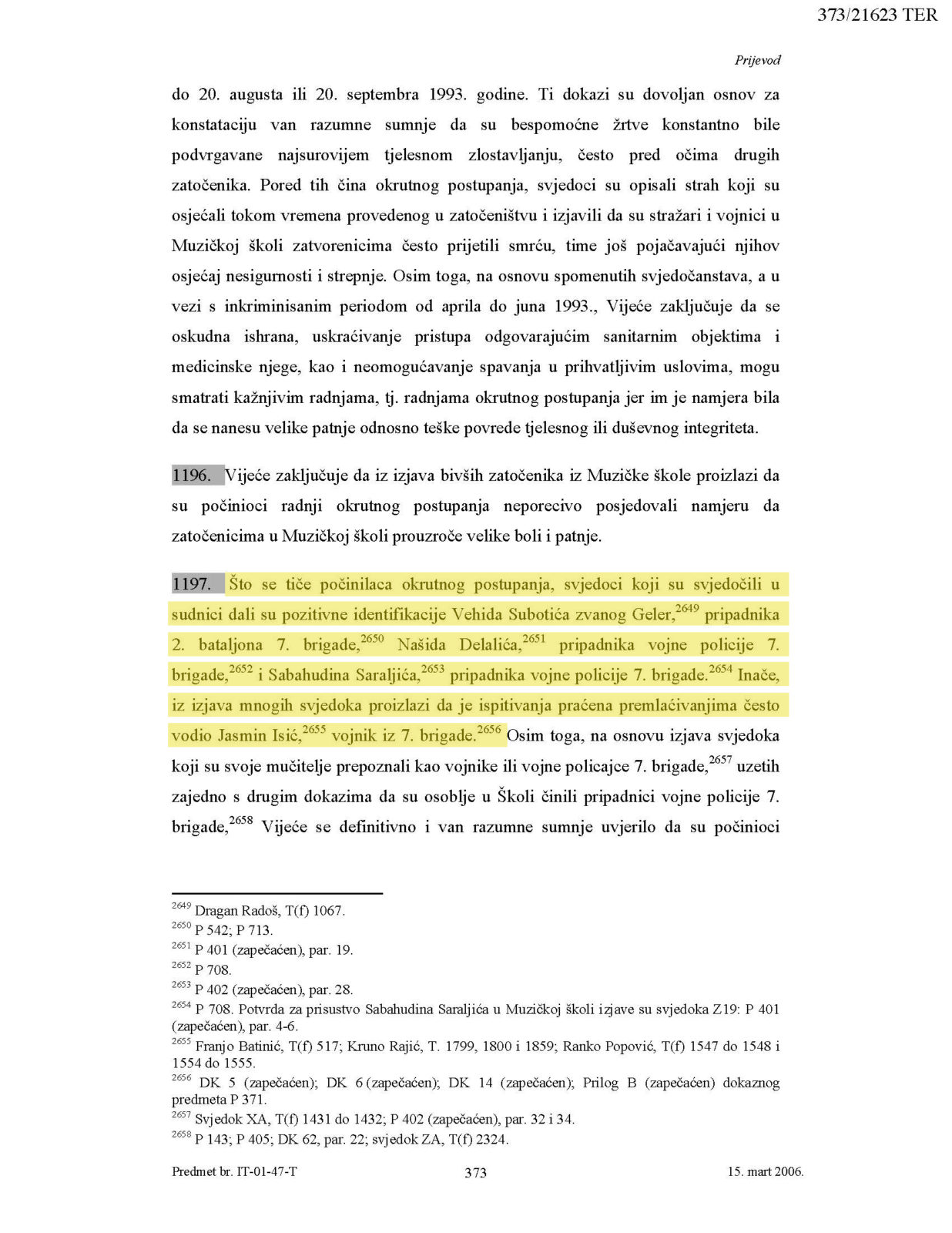

Jasmin Isic is one of the people mentioned in the ICTY’s verdict in the trial of Hadzihasanovic and Kubura. The Tribunal determined that he was at the Music School at the time of the crimes, and many witnesses said he was present during beatings.

“The interrogations, often conducted by Jasmin Isic during the night, were regularly accompanied by beatings of ten minutes or so administered by shovel handles,” the verdict said.

“The blows rained down on the detainee under interrogation whenever his answers did not satisfy the interrogator or interrogators or even whenever a prisoner opened his mouth to answer. The detainees were also regularly hit by the guards in the basement cell,” it added.

BIRN was unable to reach Isic for a comment. Vrvilo, who said that Isic was one of the main interrogators at the Music School, said he had heard that the former guard had died. BIRN was unable to confirm this independently.

The ICTY’s verdict in the Hadzihasanovic and Kubura trial also said that witnesses also identified several others as “perpetrators of the mistreatment”. It named Vehid Subotic, alias Geler, a member of the 7th Brigade 2nd Battalion, Nasid Delalic, a member of the 7th Brigade Special Military Police, and Sabahudin Sarajlic, also a member of the 7th Brigade Special Military Police.

In a separate case, the Bosnian state court sentenced Subotic to 11 years in prison for participating in the murders of six civilians and the mistreatment of another in the village of Dusina, near Zenica, in January 1993. He is currently serving his sentence. BIRN was unable to get in contact with Sarajlic.

‘If they told us to use force, we did’

The evidence that the ICTY relied upon when citing the accusations against Delalic and Sarajlic is sealed, according to the Hadzihasanovic and Kubura trial verdict, so BIRN was unable to see it.

But in December 2022, Delalic gave an interview to BIRN by telephone and agreed to be interviewed again at his house near Travnik.

During the first interview over the phone, Delalic confirmed that he was a military policeman deployed at the Music School in Zenica, which the Hadzihasanovic and Kubura trial verdict said the Bosnian Army used as a detention centre.

Asked if he participated in the coercion of prisoners who were being questioned, he said they “only acted on orders” to find out information about the movements and intentions of those who had been detained.

Asked who gave the orders, Delalic said: “You couldn’t just work unilaterally. Jusuf Karalic was there, Jasmin Isic was there, Edin Arnautovic was there, and Nesib Talic, he was the chief of security.”

In the subsequent face-to-face interview, Delalic told BIRN that he arrived at the Music School in January 1993 and, after armed conflict between the Bosnian Army and the Croatian Defence Council, HVO broke out in April, there were “mass arrests”.

He recalled that “about nine Croat soldiers” were brought to the Music School from Podbrijezje, near Zenica, and locked up in the basement.

“When the interrogations began upstairs, the commander was there – I know that Jusuf Karalic, chief Nesib Talic, officer Jasmin Isic were there,” he said.

He added that the prisoners were mostly interrogated by Talic and Isic in the presence of military policemen.

During the interrogations, prisoners were told to “confess, or else you know what the procedure is”, he explained.

“The procedure was – everyone had batons… If they whacked him once or twice for example and if the man confessed, he would go back down and it was finished. He wouldn’t be interrogated anymore,” Delalic said.

He added that no one was allowed to hit a detainee unless ordered to do so.

“If our superiors, be it the commander or deputy or chief, told us to use force, we had to use it. Or else you know what would happen to you – a court martial or even worse,” he explained. He added that they were not allowed to hit prisoners on their heads.

He said he was present during interrogations two or three times, and admitted that sometimes had to carry out these orders to assault detainees, but insisted that he usually volunteered to be deployed elsewhere in order to “escape from that”.

Delalic said that anyone was allowed enter the premises where the prisoners were being held, and that they were beaten by Arabs, Iranians and Turks who were being accommodated in one room at the Music School. He said he didn’t know why the foreigners were there and what their mission was.

The ICTY’s trial chamber discussed the presence of ‘mujahideen’, Islamic fighters from Middle Eastern countries who fought for the Bosnian Army. But in the verdict, it observed that not a single piece of evidence was presented to the prosecution’s allegation that mujahideen who were subordinate to the 7th Muslim Brigade had participated in the cruel treatment of prisoners held at the Music School. The verdict said the perpetrators of the cruel treatment were members of the 7th Muslim Brigade, mostly military policeman.

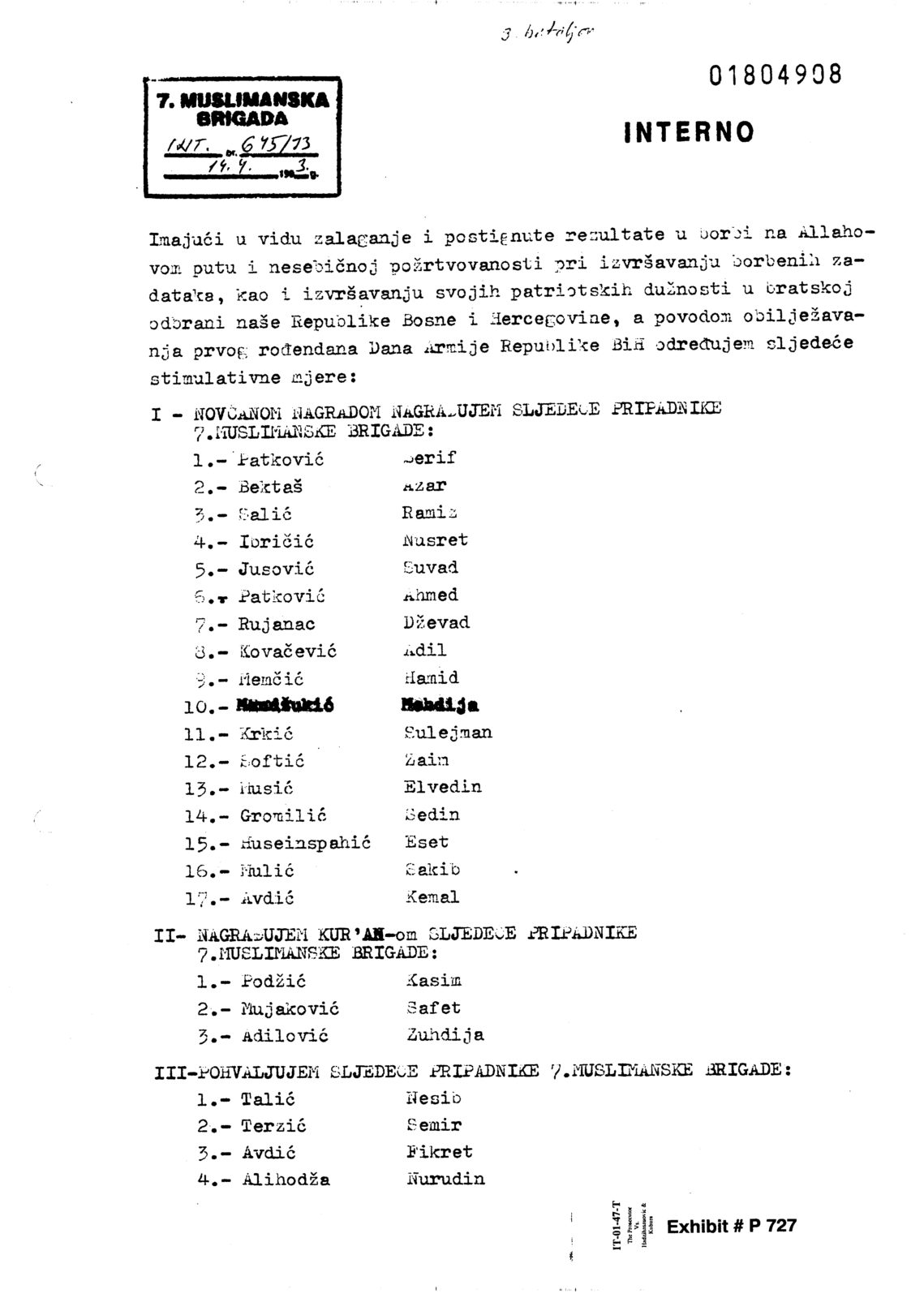

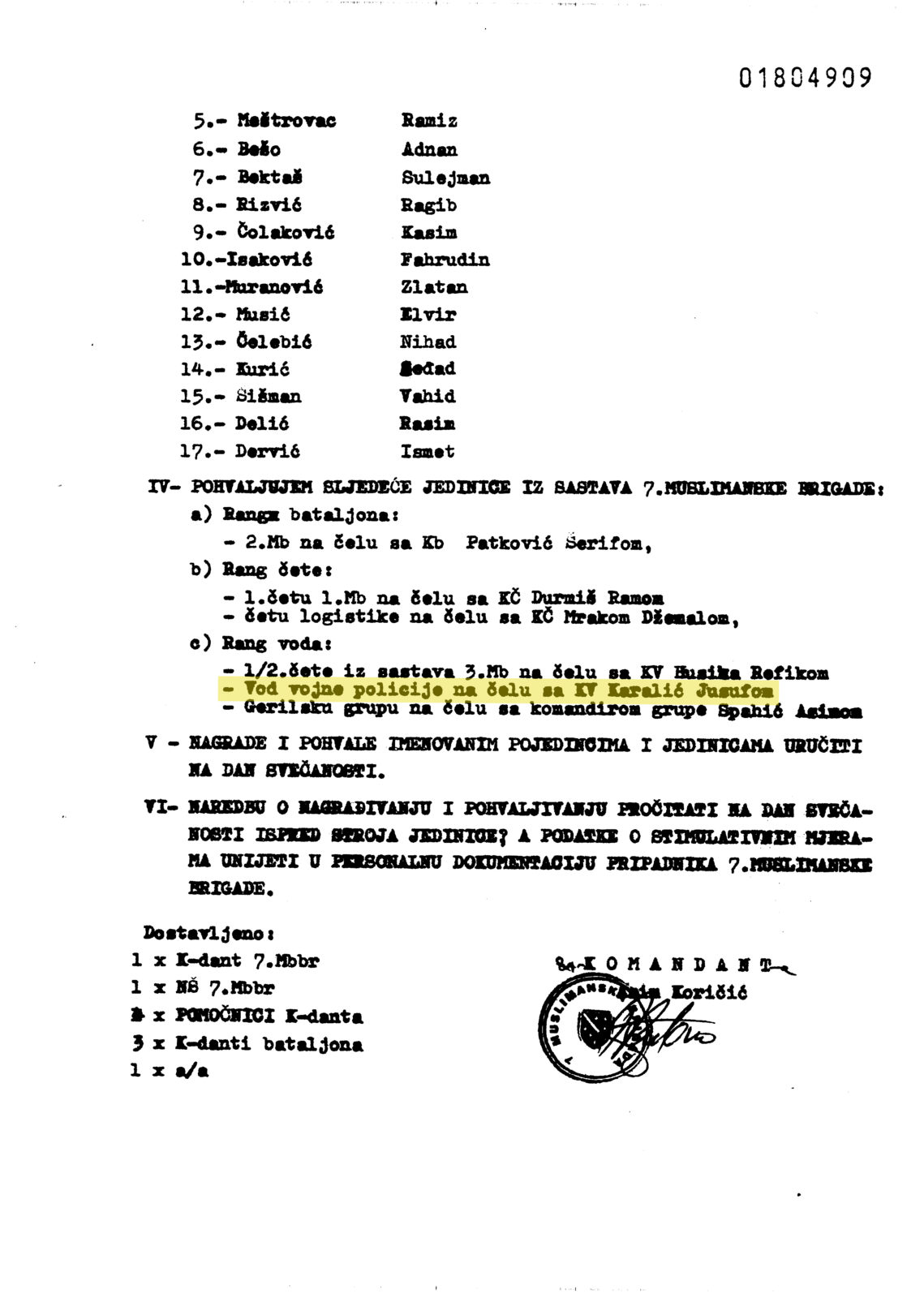

In the verdict convicting Hadzihasanovic and Kubura, the court mentioned as evidence a list of members of the 7th Muslim Brigade’s military police squad, dated September 29, 1993. The list included Sarajlic and Delalic, amongst others.

BIRN contacted one of the people on the list by phone, Vejsil Lusija, who said that he was chief of security Nesib Talic’s driver.

Lusija said he only went down to the basement where the prisoners were held a few times.

“I saw them downstairs sitting and smoking, but I didn’t approach them, nor did I have contact with any of them,” he said, adding that he didn’t notice that any of the detainees had injuries.

‘Nothing should be done to the prisoners’

The Hadzihasanovic and Kubura verdict stated that Jusuf Karalic, commander of the 7th Muslim Brigade’s military police squad, was at the Music School while it was being used as a detention facility.

According to the ICTY’s trial chamber, Karalic introduced himself to the detainees at the Music School as the 7th Muslim Brigade’s military police commander in late May 1993, when Ante Viskovic, who had been the head of the security services in Zenica and Sarajevo, was being released.

Karalic assured the detainees that from then on they no longer had any reason to be fearful. He punished a guard who had entered the basement to beat up prisoners, and posted other guards to protect them, according to the ICTY’s trial chamber.

He also carried out an investigation into thefts of property from detainees. After their property was found, it was returned to them, the Hague court said.

Karalic confirmed to BIRN in a telephone interview that he was the commander of the 7th Muslim Brigade’s military police squad and that he was at the Music School when prisoners from the town of Kakanj were being held there.

“I asked the commander to let those people take a bath during those days, to let them receive visits – they had visitors from Kakanj and in a couple of days all of them left,” Karalic said.

He explained that he was not at the Music School all the time because he was deployed in the field. He said that when he left, he gave an order to his deputy that “nothing should be done to the prisoners”. Their families were also allowed to bring clothing and food to them, Karalic said.

Karalic was also at the Music School before Ante Viskovic’s release in May 1993, according to detainee Kruno Rajic, who told the ICTY that he saw Karalic often. Rajic said Karalic was able to see the injuries sustained by the detainees from the beatings that happened at night.

But the ICTY’s trial chamber also cast doubt over Rajic’s testimony, saying it was contradictory because he also stated that he thought that Karalic was not aware of any cruel mistreatment of detainees before Viskovic’s release.

Karalic denied that he saw injured detainees: “I did not see injures as far as the people from Kakanj are concerned… While I was there, they never lacked anything, I considered them to be my brothers, irrespective of who they were, whether they were Serbs or Croats, although there were very few Serbs,” he said.

He acknowledged that he did see one person who had injuries, but he didn’t know who had hit him.

“While I was staying there, I never saw anyone . But those were soldiers, you know what can happen while you are not there, for instance… but while I was there, I never ordered anyone and always demanded that none of them should be even touched, no matter who they were,” he said.

The Hague Tribunal acknowledge that Karalic took action to improve the conditions for the detainees, but questioned why he did this.

“It is possible that Jusuf Karalic decided to punish the excesses previously committed by his subordinates on his own initiative. Alternatively, the chamber concludes that the steps taken by Jusuf Karalic to improve the lot of the detainees immediately followed the release of Ante Viskovic, and was made possible by the intervention of the accused, Hadzihasanovic,” the verdict said.

Karalic said that after the war, people thanked him for treating them well while they were detained at the Music School.

“Just put yourself in my shoes to see how it was. Many perhaps think that what I did was wrong, but I think, as a man, that I did the right thing,” he said.

‘We should tell the truth’

The cantonal prosecution in the Zenica-Doboj Canton was working on a case against Karalic, as well as Jasmin Isic, Sabahudin Sarajlic and Nasid Delalic and others. The case was transferred to the state-level prosecution for further processing in December 2011.

The state prosecution said it has several cases that are at different stages related to what happened at the Music School in Zenica and crimes reported to have been committed by members of the 7th Muslim Brigade’s military police squad in 1993.

“This concerns crimes against several dozen captives. Several civilians died as a result of the abuse,” the prosecution told BIRN.

“The victims were mostly individuals who were captured in the wider Zenica area. The information that’s available suggests that the Music School building was under the management of the 7th Muslim Brigade military police of the Bosnian Army,” the prosecution added. It said it could not provide more details about the cases.

Nasid Delalic said he was speaking openly to BIRN about what happened at the Music School so that in the future, no one can say that “Nasid committed all the crimes” in 1993.

“We shouldn’t turn our back on this and we should tell the truth, if we want the truth. I could have said: ‘I don’t know, I don’t remember, I wasn’t there.’” Delalic said.

Three decades after the crimes at the Music School, Anto Vrvilo, who was detained and beaten for two months there, said he has now lost all hope that the direct perpetrators will ever be prosecuted.

“It’s over,” he concluded. “If it was supposed to happen, it would have happened by now.”

You can browse them with Windows > Photo Viewer or Mac > Preview.