This post is also available in: Bosnian

Students attend lectures in the former camp buildings, which now belong to the University of Mostar.

Former camp inmates like him have no access to the site of the former camp, where they experienced much suffering years ago.

Batlak remembers the brutality he witnessed from the window of the pavilion where he was held, including when people were beaten after an inmate had managed to escape.

“I remember very well when one man begged them to kill him and end his suffering; they literally hit him on the head with buckets full of water,” he said.

“When I saw them a few days later, I couldn’t believe the scene; that a man could swell up so much and his head could get so big. People were completely distorted ,” Batlak added.

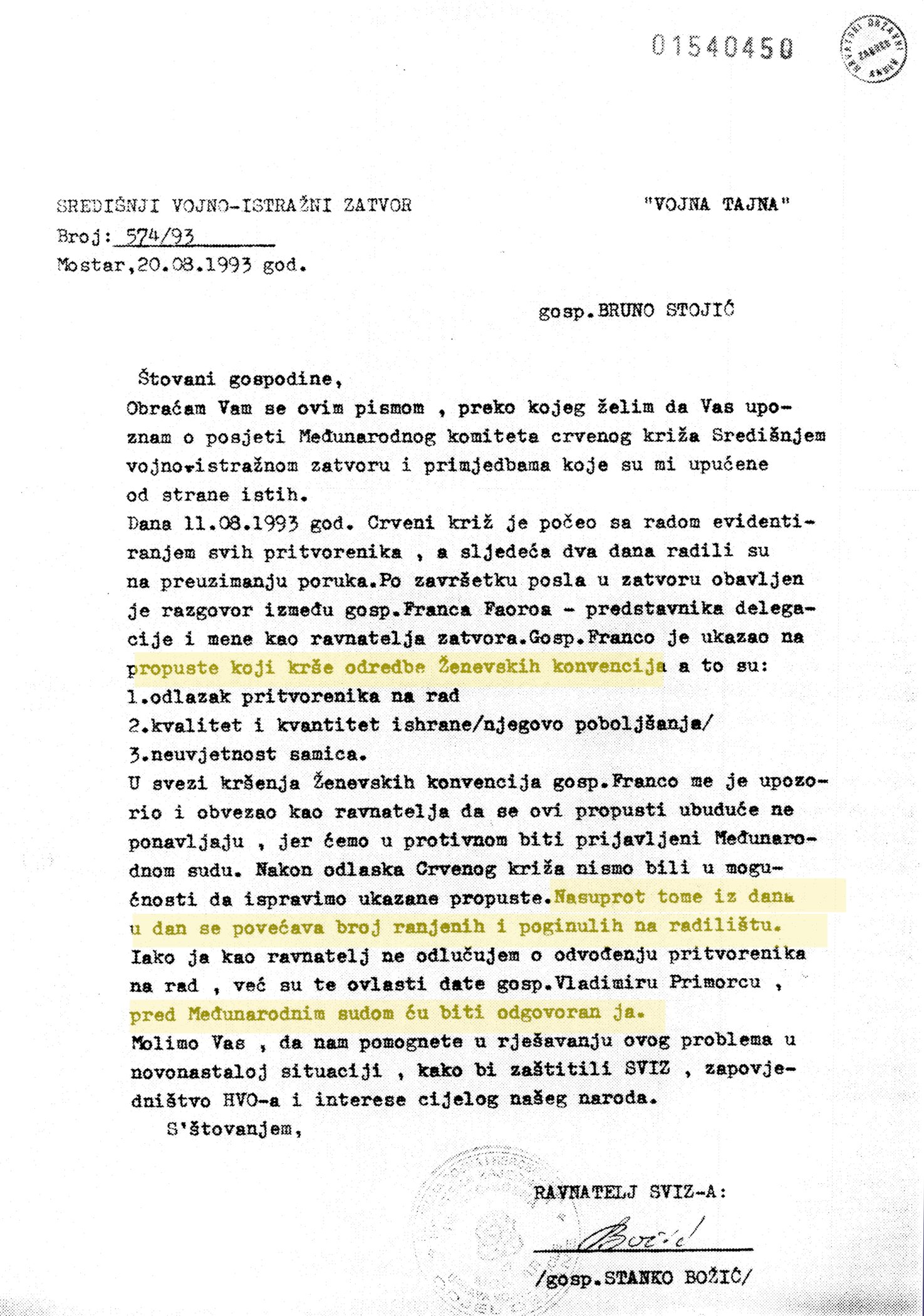

A month after his detention began, on August 11, 1993, the International Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC, visited the camp and concluded that the Geneva Convention on the Protection of Prisoners of War was not being respected.

It said the conditions, hygiene and food were poor and detainees were being taken to do forced labour on front lines.

The chief warden, Stanko Bozic, conveyed their remarks to Bruno Stojic, defence minister of Herzeg-Bosnia, in a letter a few days later.

He stated that, as a warden, he was obliged not to repeat such failures “because otherwise we will be reported to the international court”. But Bozic later admitted the mistakes were not corrected.

“On the contrary, the number of those wounded and killed at the workplace is increasing by the day,” he wrote on August 20, 1993, asking Stojic to help solve problems.

Earlier Bozic had warned that he would stop taking prisoners to work if they were going to be beaten. In a report to Valentin Coric, Zvonko Vidovic and Berislav Pusic, he noted that two prisoners, Sead Ramic and Ibro Cilic, had been wounded during forced labour and been transferred to Mostar.

BIRN analyzed this correspondence and other documents from the first-instance verdict of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ICTY, by which Jadranko Prlic and other leaders of the so-called Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosna were sentenced to a total of 111 years in prison under the second-instance verdict in November 2017.

We found the names of four people whose responsibility was never determined in court proceedings.

In the final verdict, the former Prime Minister of Herzeg-Bosna, Prlic, was sentenced to 25 years in prison. The statelet’s former Minister of Defence, Bruno Stojic, and two former Chiefs of Staff of the Croatian Defence Council, HVO, Slobodan Praljak and Milivoj Petkovic, were sentenced to 20 years each.

Valentin Coric, former chief of the HVO Military Police Administration, was sentenced to 16 years and Berislav Pusic, president of the Commission for the Exchange of Prisoners, to ten years.

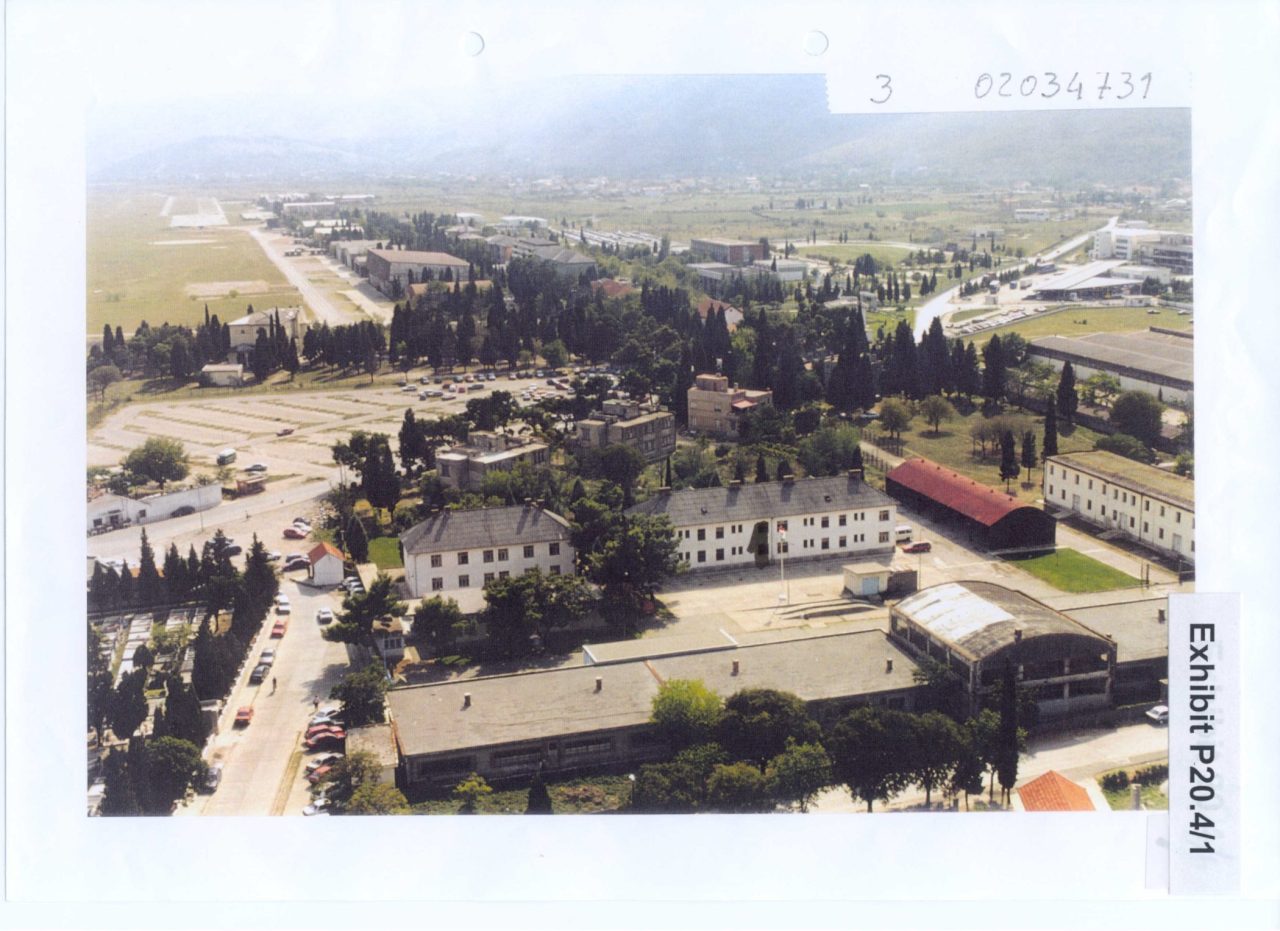

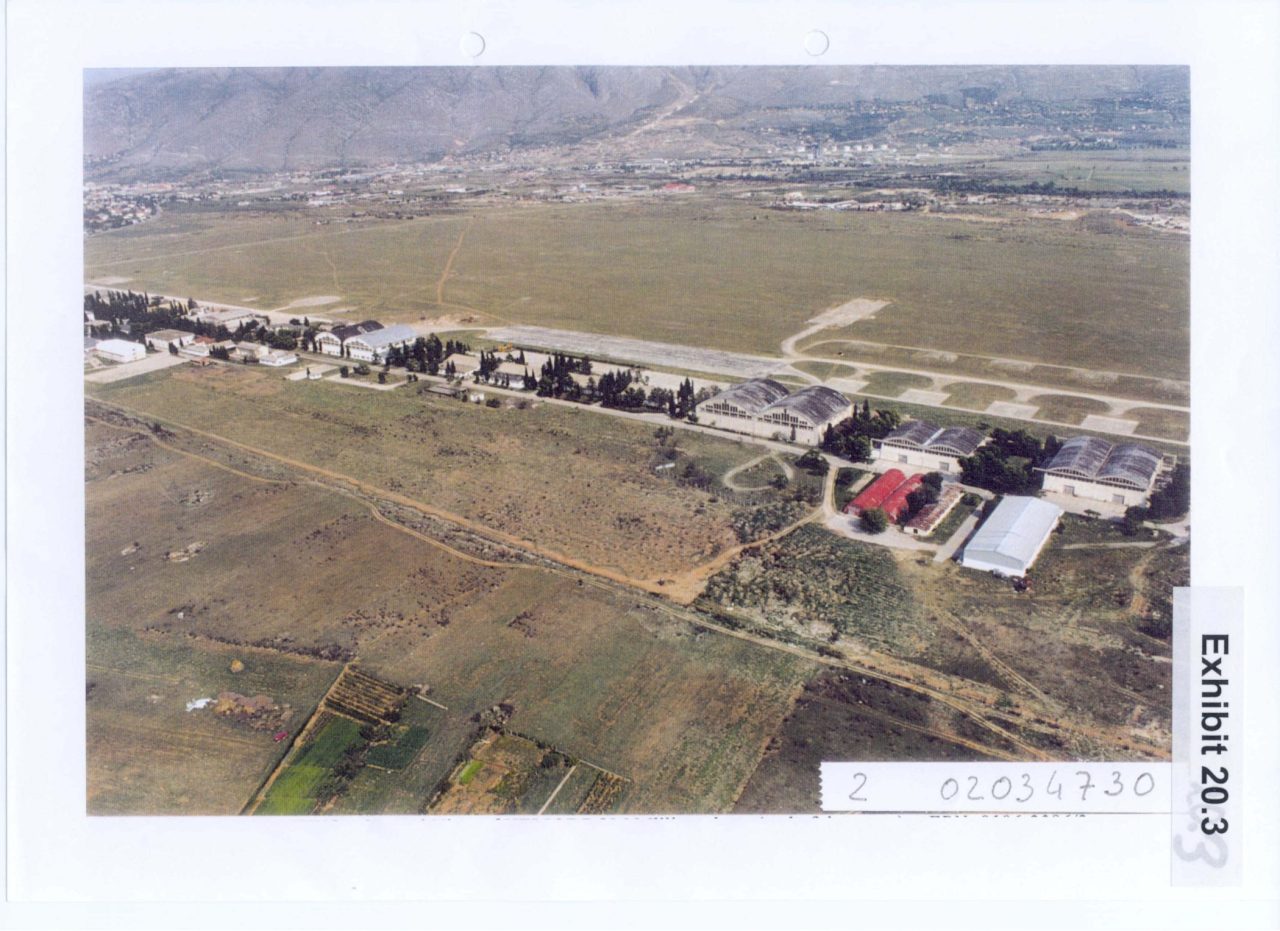

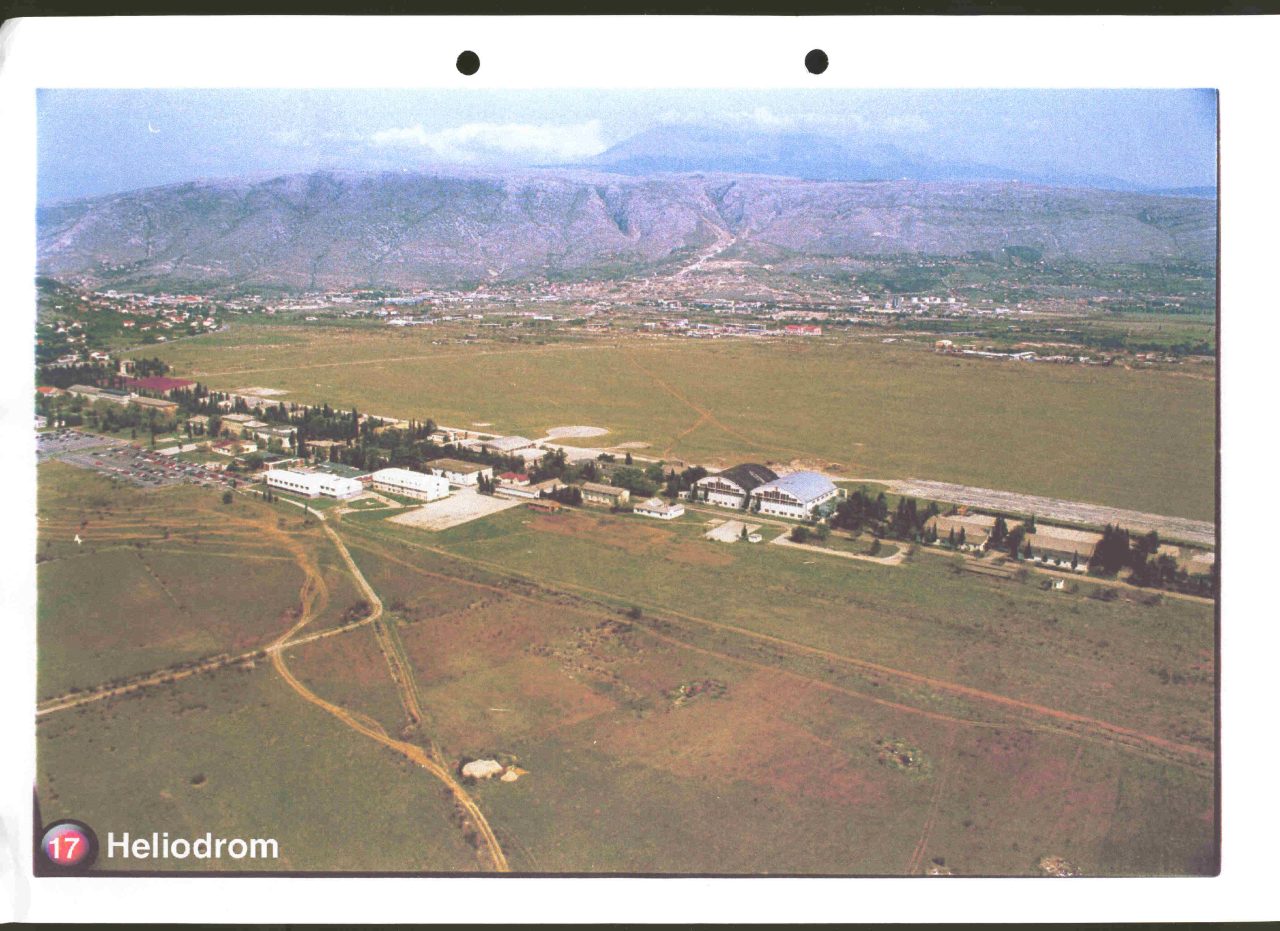

Photograpy of “Heliodrom” presented at the trial in ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Photograpy of “Heliodrom” presented at the trial in ICTY. Photo: ICTY

The ICTY judges determined that the HVO took over the former military complex of the Yugoslav People’s Army JNA near Mostar in June or July 1992, to use as a barracks.

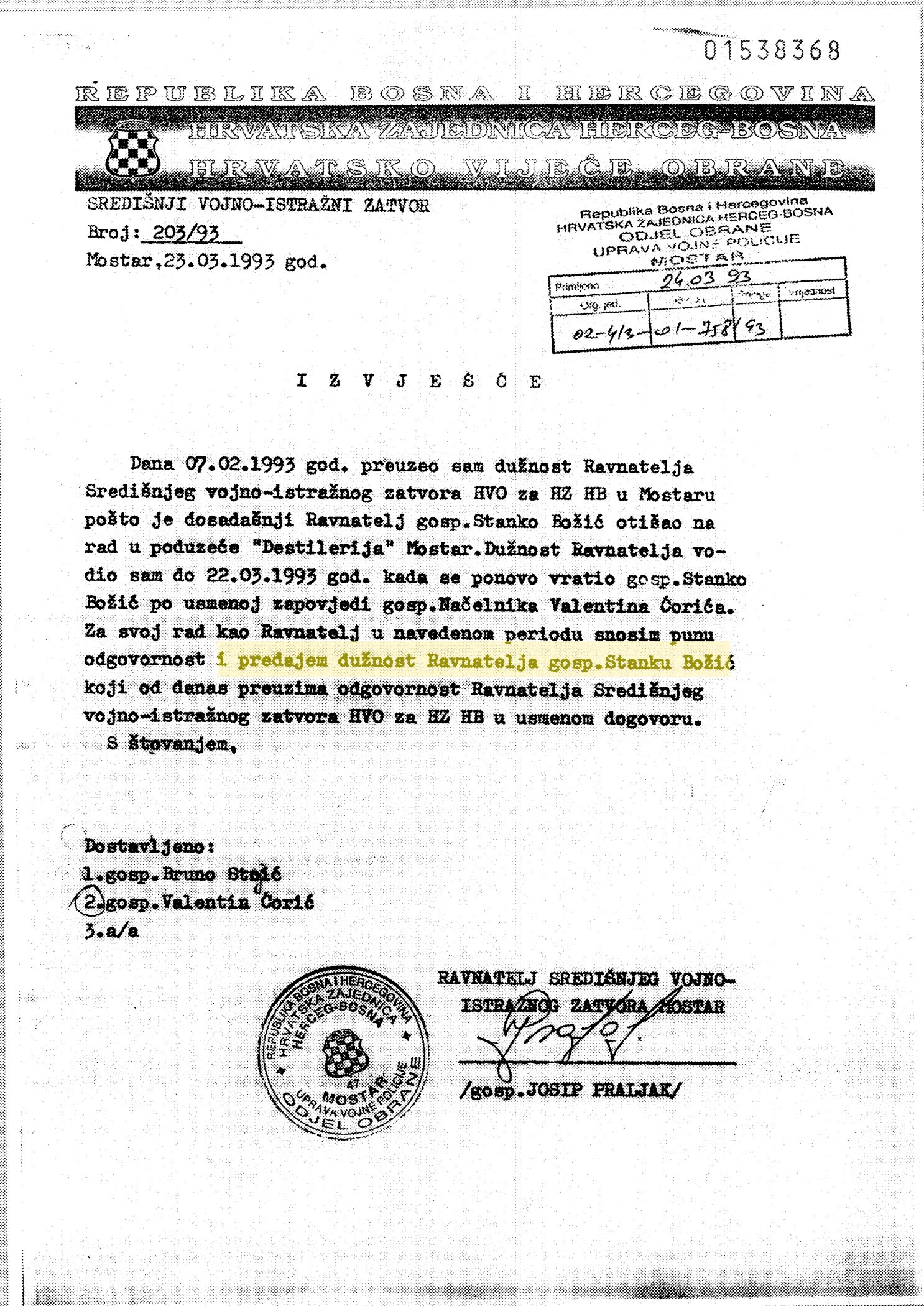

Judges concluded that Coric had ordered the establishment of the camp at Heliodrom, and that on December 21, 1992, he had appointed Bozic as the warden.

According to the verdict, Bozic left his post with the approval of Coric on February 7, 1993, to return to the company where he had worked before the war but had returned on March 22. He remained warden until April 1994.

In September 1993, Bozic forbade prisoners from Heliodrom being taken to work on front lines. But, as the Chamber concluded in the verdict against Prilic and others, the practice continued.

Bozic has also testified about this in trials held before Bosnia’s State Court.

Batlak recalled that Bozic was warden of the camp during the whole 253 days he was imprisoned at Heliodrom.

“A man without whose knowledge no one could be taken to forced labour or mistreated after all found out he had to do something,” commented Batlak. He recalled Bozic “a man who did nothing”.

“That official, because he was appointed to that position, must be held accountable for the crimes committed against innocent people,” Batlak added.

But Bozic has never been held accountable in a court.

Asked by journalists, he declined to talk about his role in the 1992-5 war in Bosnia. “I don’t want to talk and don’t call me anymore,” Bozic told a BIRN reporter, hanging up. Later, he also did not respond to a message sent to him by journalists.

The Hague judges concluded that no one responsible at Heliodrom, or any other member of the HVO, was ever punished for sending detainees from the camp to work on front lines.

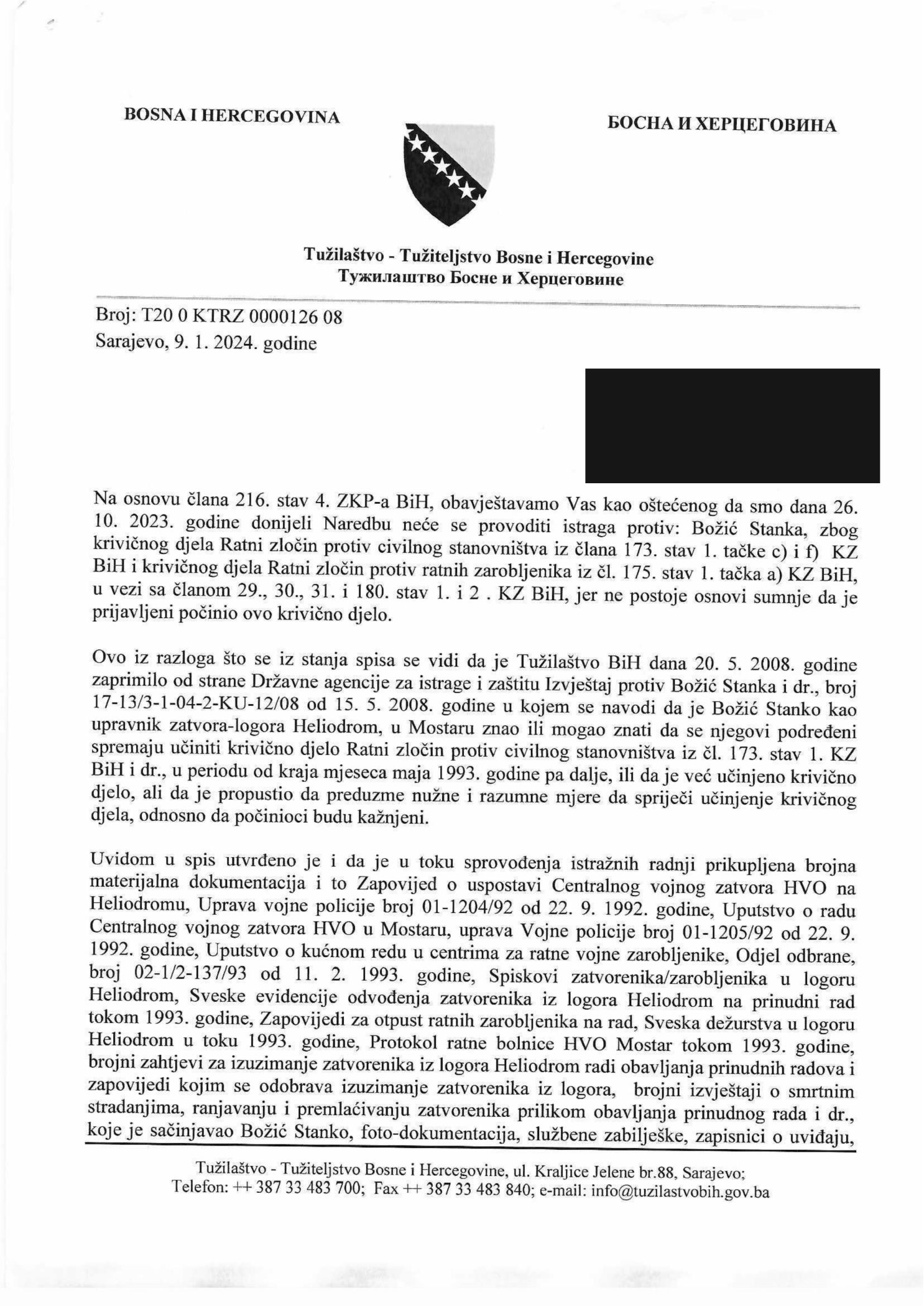

BIRN has also had access to a Bosnian State Prosecution document, which informs the former Mostar camp inmates’ association that it will not conduct an investigation into Bozic “because there are no grounds for suspecting that the reported person committed a criminal act”.

It notes that a review of the file had determined that an analytical report, “Bozic Stanko: taking prisoners to forced labour from the Heliodrom camp”, was created on July 19, 2022.

According to the prosecution, from the database of open war crimes cases from February 28, 2022, it can be seen that Bozic was not named in any other cases handled by this prosecution. Bozic was also never registered in the criminal records of the Mostar Police Adminstration.

Prosecution couldn’t establish what warden knew

In its decision not to investigate Bozic, the Prosecution states that a military expert reached an opinion that the Helidrome functioned mostly under the authority of the Military Police Administration.

According to the expert, the warden had under his control the entire security service and was responsible for their work and treatment of prisoners and was obliged to take measures preventing abuse of detainees.

“Based on the available documentation, it is not possible to determine whether the warden of the … prison was really aware of the abuse of detainees by guards-military policemen,” the prosecution document states.

.

The expert further stated that, according to the available documentation, the warden did not send any prisoner to forced labour without first receiving an order, and he could not prevent abuses during forced labour.

The expert could not determine whether the warden knew about abuses in the camp itself but noted that he sent a series of reports in which he talked about the abuse of prisoners when they were taken to work, and also demanded punishment of the perpetrator in some cases.

The expert concluded that the warden cannot be held responsible for forced labour on the lines where combat operations were carried out

Emir Hajdarovic, another former inmate at Heliodrom and president of the Mostar camp inmates’ association, says they are disappointed by the prosecution decision not to investigate Bozic.

“This means insulting not only the inmates of Heliodrom but also those in all the other camps … by acquitting one of the most responsible persons in one of the camps,” he said.

Witnesses have lost trust in the State Prosecution and in cooperation with it, Hajdarevic added.

He says former camp inmates do not even trust the Cantonal Prosecution in Mostar.

Bosnia’s State Prosecution confirmed to BIRN that Bozic was warden of the Heliodrom and that an order not to conduct an investigation against him was issued.

But it also stated that a new case opened for the same criminal actions in Heliodrom is now in progress, and that a proposal has been submitted to the State Court to transfer the proceedings to the Cantonal Prosecution in Mostar.

The prosecution refused to show BIRN the order not to conduct an investigation, saying it was not in the public interest.

If the order was delivered to journalists, the investigation in cases related to the case of Bozic being conducted now by the Prosecutor’s Office and by the Republic of Croatia, could be called into question, it stated.

Warden told superiors: ‘I don’t know what to do’

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Apart from Bozic and those convicted in the case Prlic et al. – Milivoj Petkovic and Slobodan Praljak, authority to grant permission to take detainees from Heliodrom to work from June 1993 to March 1994 belonged to the commander of the Defence Zone of Mostar, Zlatan Mijo Jelic, according to the verdict He is on the run in Croatia.

Approvals could also be given by the commander of the “Convicts Battalion”, Mladen Naletilic, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for his role in the ethnic cleansing of Bosniak civilians from the Mostar area by expulsions, killings, illegal imprisonment and forced labour.

Among other names listed in the verdict, BIRN identified two more people who, according to the Hague judges, could have issued permission to take prisoners from Heliodrom to work.

These two are the assistant chief of the Military Police Administration in the summer of 1993, Radoslav Lavric, whose family now lives in Ljubuski, southwest Bosnia, and an official in the Department for Criminal Investigations of the Military Police Administration, Zvonko Vidovic, from Mostar.

Bosnia’s State Prosecution could not confirm to BIRN whether they are included in the now ongoing Heliodrom investigation.

“Several cases in which the Heliodrom camp is mentioned have been registered in the Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina and a case is in the reporting phase related to events at that location in 1993 and 1994,” the answer stated.

BIRN could not get a comment from Lavric, after leaving a phone number with a request for an interview. He did not respond by time of publication.

Vidovic meanwhile told journalists in Mostar he could not have had any authority to take prisoners to work, especially before July 1, 1993.

“I don’t know of any order signed by me that … that taking people to work is allowed,” he said.

“Battalion company commanders would come with a paper: ‘Give me 10, 20, 50 ’ – and poor Bozic allowed it,” Vidovic added.

According to Vidovic, after July 1, Bozic started informing him about what was happening at Heliodrom.

“It can be seen from these documents that over 2,000 people were indiscriminately brought in who were not interesting for us, and, as head of the department, I was asking to create a section within Heliodrom only for military persons,” he said.

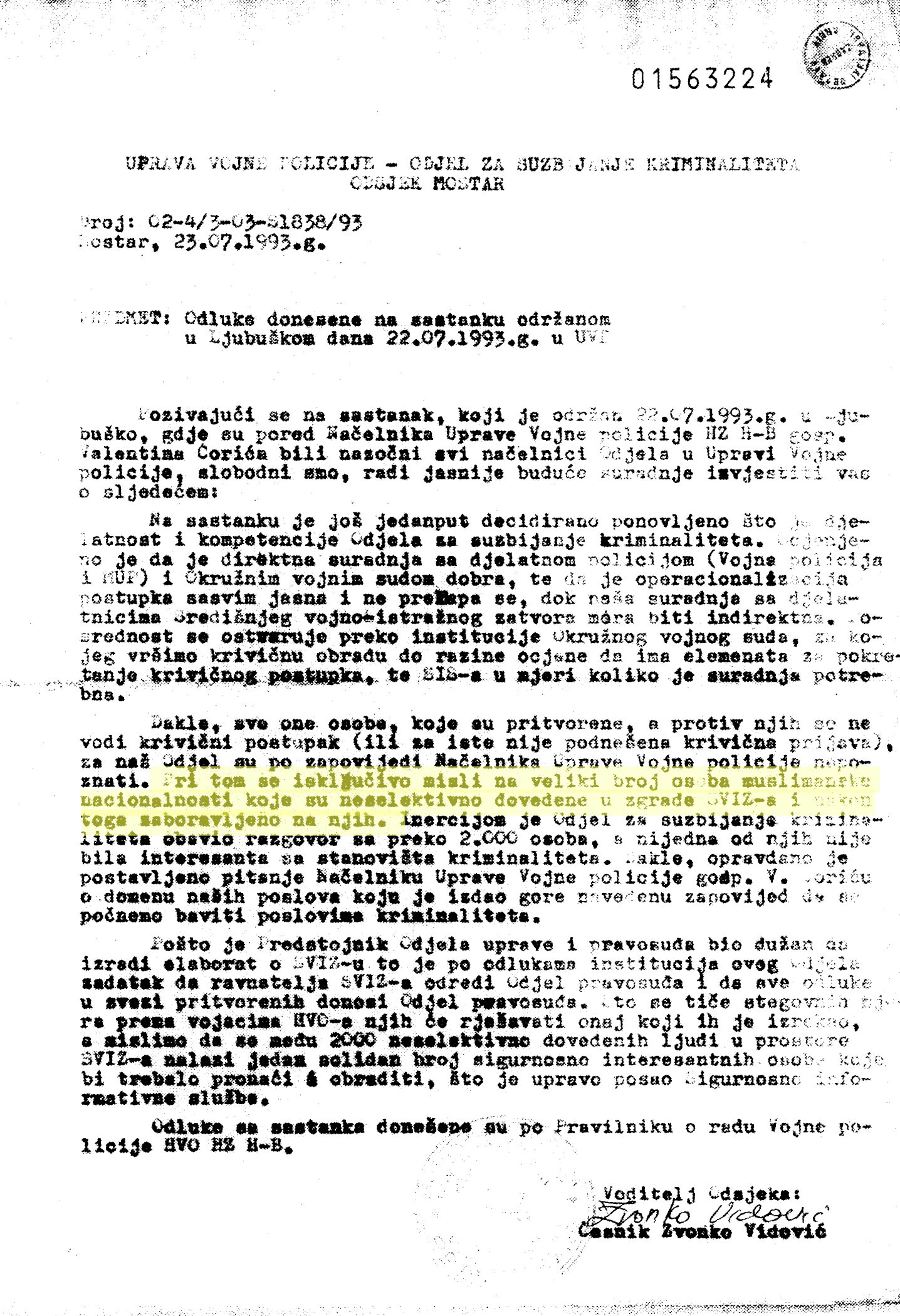

In a document dated July 23, 1993, on decisions made at the meeting the day before in Ljubuski, Vidovic states that all those people who had been detained – against whom no criminal proceedings were being conducted or filed by the Department for the Suppression of Crime – are by order of the Military Police Administration unknown to the criminal investigations department.

Apart from Coric, all the chiefs of departments in the Military Police Administration attended the meeting.

“This refers solely to the large number of Muslims who have been brought unselectively to the SVIZ (Central Military Remand Prison) buildings and who have since been forgotten. By inertia, the Department for Suppression of Crime interviewed over 2,000 people, and none of them were interesting from the standpoint of crime,” the document states.

Vidovic said these civilians should have been dealt with by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and captured members of the Bosnian Army by the Security and Information Service, SIS.

On September 29, 1993, Vidovic informed Stojic “about the events that have harmed and are harming the development of … the military and civilian structures of the Croatian Defence Council of the Croatian Republic of Herceg-Bosna, regarding the hierarchical structure and the impossibility of implementing that structure.”

While noting the problems of taking detainees from Heliodrom by order, Vidovic asked for a unified position to be taken on the non-interference of HVO unit commanders in the affairs of the military and civilian police and the judiciary, and to resolve the problem of Heliodrom.

“It is more than evident that, in that facility, they do not work according to the procedural rules of the HVO; people are brought in and taken away without anyone’s knowledge, the hierarchy and orders of superiors are not respected. It seems anyone can order the release of certain types of detainees, without consulting the police or the judiciary. I will not even talk about detained people of Muslim nationality,” Vidovic wrote.

“I’m doing this because Stanko Bozic directly addressed me several times on our arrival at Heliodrom and said: ‘I don’t know what to do,’” explained Vidovic.

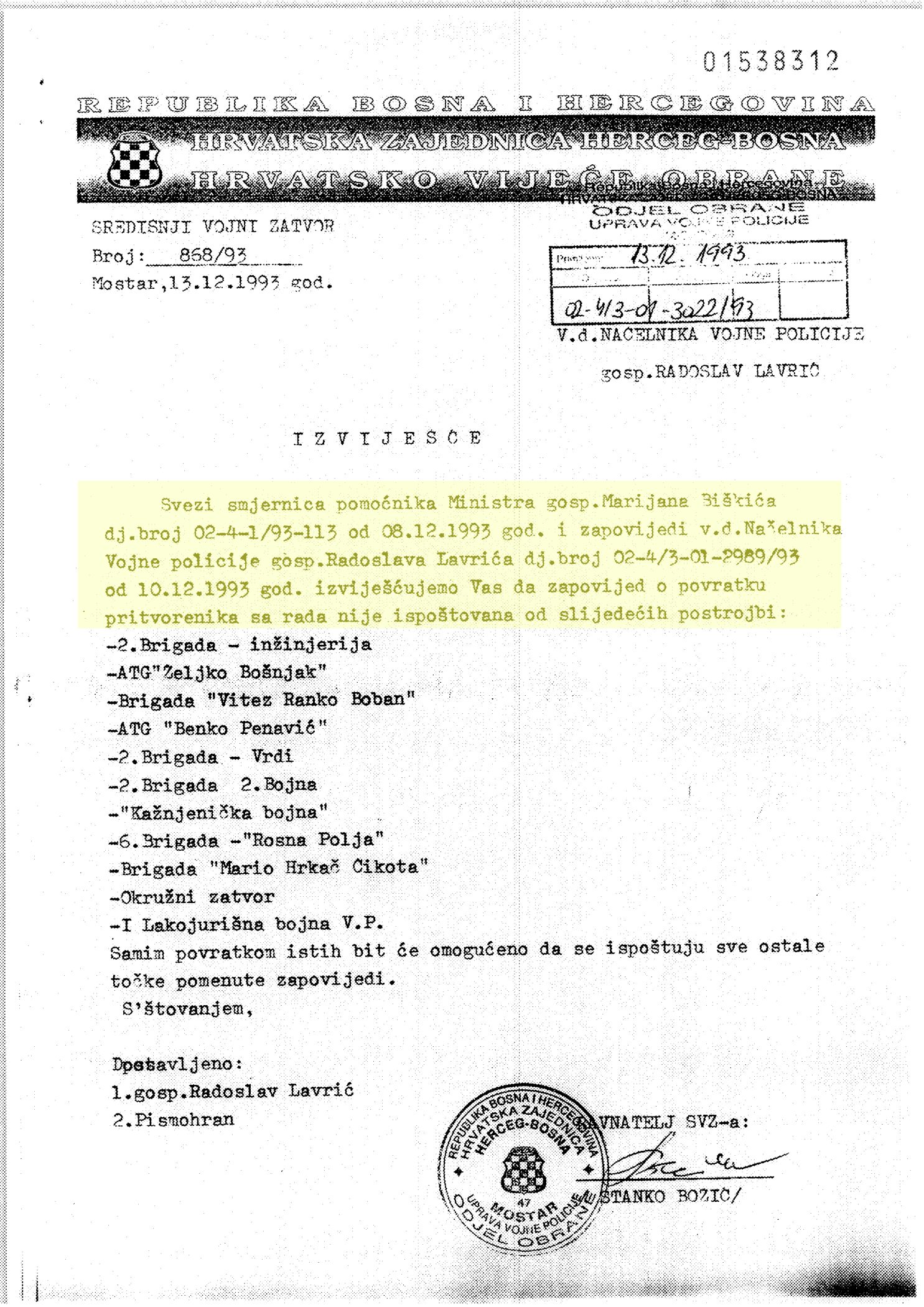

He said the reports he had sent to higher-ranking officials were acknowledged – but that was all. He believed that the hands of Bozic, who had sent the letters, were also tied. In a report to Lavric dated December 13, 1993, Bozic mentioned units that did not return prisoners from work.

“Poor Bozic at one point even wanted to give up. He wrote non-stop … Then, he had these kind of guards that were like this and like that. There were those who were OK, but there were also those who behaved sadistically,” Vidovic said.

Military Police regularly beat detainees

Batlak said he was detained first at the high school for seven days. “I made a little joke that I had passed the intermediate level, and that, as a university-educated person, I was transferred to the Central Prison. It was a slightly more cramped space with bars on the windows,” he told BIRN in March 2024, on the anniversary of the closure of the Heliodrom.

He was held in Heliodrom from July 10, 1993 to March 19, 1994.

Batlak said there were differences in conditions; the worst were in the sports hall, while the most comfortable, relatively, were in the former high school.

In the central prison area, there were solitary cells in the basement rooms, where people were exposed to torture, he explained. Male prisoners were on two floors while women were in the basement. He said some children were also imprisoned there for a while.

The chamber that sentenced Prlic and others to a total of 111 years in prison for war crimes against Bosniaks analyzed the evidence related to the bringing of Bosniaks to Heliodrom during the wave of arrests on May 9 and 10, 1993 in western Mostar, then in the second half of May 1993 and after June 30, 1993. It also referred to detainees brought to Heliodrom from other detention centres.

“The overall testimonies presented to the chamber indicate that women, Muslim members of the HVO, members of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as men who were not members of any armed forces, were among the detainees there. Among the detainees were persons younger than 15 and older than 60,” the verdict read.

The verdict concluded that, from May 1993 to mid-April 1994, members of the Military Police in charge of guarding detainees regularly and severely beat the detainees with various objects, sometimes for hours, until victims lost consciousness, and insulted, threatened and humiliated them.

As stated, members of the HVO, specifically the professional units of the Convicts Battalion” and the Bruno Busic Regiment, as well as other persons whose identity cannot be determined, severely and regularly beat prisoners.

The first-instance verdict concluded that the conditions of detention in solitary confinement were extremely bad. The hygienic conditions from May 1993 to mid-April 1994 were generally poor and overcrowded.

“The chamber established that some detainees who were imprisoned at Heliodrom from May 9 or 11, 1993 to April 19, 1994, received very little food, which was also of poor quality. That is why these people, during their imprisonment at the Heliodrom, suffered from hunger and lost weight, some of them drastically,” the verdict said.

Prisoners died working as ‘human shields’

The first-instance verdict also considered prisoners taken from the Heliodrom to carry out work outside the camp.

The verdict was that it appears that the HVO from May 1993 to March 1994 took detainees from Heliodrom to work in Mostar’s Santiceva Street and Boulevard, where the front line between the HVO and Bosnian Army lay.

“Those works consisted in strengthening or erecting fortifications, that is, collecting the corpses of HVO soldiers or Muslims who’d died while working on the conflict line,” read the verdict, which stated that they were also taken to other locations.

According to the chamber, the HVO Military Police took the detainees out of Heliodrom to assign them to various HVO units for work. Among them was the unit of Vinko Martinovic, alias “Stela”, who was sentenced, together with Naletilic, to 18 years in prison.

Because they were exposed to the crossfire of the warring sides, dozens of detainees were killed or wounded while performing forced labour on front lines. According to the verdict, some of these were killed or wounded by HVO forces.

Some detainees from Heliodrom died, according to the chamber, working as “human shields”.

In its verdict, the chamber explained that units that wanted to use detainees from the Heliodrom for work had to submit a written request.

The chamber stated that, from the instructions issued in August 1993 by the de facto deputy warden of the Heliodrom, Josip Praljak, no unit could take detainees if they had not previously submitted a written request, although it does not say who this request should have been submitted to.

The verdict also stated that, in his testimony, Praljak hsd explained that a member of the HVO unit who wanted to get detainees would submit the request to the “security shift commander” who then chose the detainees to be used for work.

“However, the chamber noted that sometimes the member of the unit that was looking for detainees was the one who chose the detainees,” the verdict said.

BIRN did not manage to contact Praljak, who testified in The Hague.

The report of the acting chief of the Military Police Administration, Radoslav Lavric, from November 22, 1993, explained that a request must be signed by the Military Police battalion or brigade commander in order to use “prisoners of war” for work.

In the Operating Instructions of the HVO Central Military Prison in Mostar dated September 22, 1992, Valentin Coric defined, among other things, the role and function of the warden at Heliodrom.

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

Photography of “Heliodrom” presented at the ICTY. Photo: ICTY

“Specifically, he was responsible for ensuring that ‘prisoners of war’ were treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions; he had to supervise the work of security personnel on a daily basis; he had to have a personal insight into the state of facilities and ‘premises’, ‘war prisoners’, as well as ‘military prisoners’, his task was to receive representatives of the ICRC,” the instruction said. The warden also had to submit daily reports to the Military Police Administration.

The chamber further stated that, between January and November 1993, a meeting was held every morning in the office of warden Bozic, where reports about everything that had happened in the prison between 4pm the previous day and 8am the current day were submitted to him.

“Under the supervision of the warden of the prison and the security commander, the ‘security shift commanders’ supervised the work of the military policemen in charge of security and provided 24-hour duty,” the chamber stated.

Talking about the time he was imprisoned in the camp, Batlak emphasizes that he was taken to work in several locations, such as Santiceva Street in Mostar, where he was exposed to harassment by HVO soldiers.

“The whole treatment when you are in a concentration camp – first, you are absolutely humiliated. If they call you a number, a thing, slave, your dignity is systematically killed,” he said.

“And when you were on the front line, you were exposed to all kinds of possible adversity … They could do whatever they wanted. And they did in many cases,” he concluded, noting that 77 people were killed while doing forced labour on the front line.

Možete ih pregledati sa Windows > Photo Viewer ili Mac > Preview.