This post is also available in: Bosnian

Kateryna’s house is like a greenhouse. There are violets everywhere. She knows everything about how to care for her flowers, the varieties and the best conditions for flowering. This hobby has become her way to cope with her husband’s disappearance in the war.

Kateryna and Andriy were a young couple who lived in one of the small villages in the north of Ukraine’s Chernihiv province. Together they raised their son, who is now a sixth-grade student.

Kateryna, whose full identity we are protecting, says that her husband had previously not served in the army due to his state of health. Nevertheless he joined up after Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

“He was patriotic. He noticed that many men in the military committee were close to retirement, so he felt an urge to protect the country,” she recalls.

Andriy was first sent for training to the city of Konotop in the neighboring region. Around six weeks later he was on the frontline in the Bakhmut region, where he stayed until the autumn of 2022.

“We talked every day. If my husband went on an assignment, he would warn me that he was going to ‘work’ and there would be no communication for a while,” says Kateryna.

Over time, the unit in which he served was disbanded, and Andriy ended up Zaporozhye, where a counter-offensive started. Later, in 2023, he underwent two-weeks army training in Germany and ended up fighting as a member of a mechanised brigade.

“In July last year, as always, Andriy warned me that he would not be in touch. He said he would call, but he did not call. A few days later, a friend contacted me and asked me if my husband had contacted me. He informed me later that he and his comrades were considered missing,” she says.

Kateryna remembers feeling confused and not knowing what to do. Eventually, she received an official notification from the military commissariat that her husband had disappeared.

She reported that he was missing to the police. Andriy’s son and parents provided DNA samples, and an investigator was appointed for the region where he had disappeared. So far there have been three different investigators assigned to Andriy’s case in less than a year, and Kateryna has spoken to each of them on the phone only once.

She says she has been contacted by representatives of the Red Cross and by the coordination headquarters working with families of the missing. “Wives whose husbands disappeared have even created a group on messenger and that is where we get most of the news,” she says. The group exchanges information about prisoners and prisoner exchanges. The family have not received any psychological support. Only once was there an offer to receive medicall treat of her son abroad, but she turned it down because the boy had never traveled alone.

In searching for clues to her husband’s fate, no one has yet seen Andriy alive or dead. For a year and three months, her family has been living in hope that he is in Russian captivity.

Kateryina believes Andriy’s brothers are in captivity, and that some of them have already been exchanged.

According to Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets, about 40 percent of those returned from captivity are people who had the status of the disappeared under special circumstances and who have not been confirmed by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

A lack of information

Families whose members have gone missing during the war face a variety of problems. Pravna Stotinu, an NGO, is an association of lawyers whose mission is to protect human rights in the context of military service and create legal mechanisms for the reintegration of soldiers.

The organization notes that since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has received more than 22,000 complaints, 3,000 of which are from the families of the missing. The total number of soldiers and civilians who went missing during the war is unknown.

According to results of a study by Čedoš Analytical Center, one of the problems faced by families of missing soldiers is bureaucracy and having to communicate with multiple institutions at the same time.

“The lack of a single body to turn to, and of a single contact person to follow up with the families at all stages, has significantly burdened the experience of families of the missing,” Cedos wrote in its analytical report.

Two of the key problems are a lack of information and confusion. Most families do not understand the process of searching for soldiers and the role of various institutions and organisations.

There have also been cases of unethical conduct by Teritorail center for recruitment representatives. For example, reports about missing persons have been handed over to children or even neighbours. As a result, families have often carried out their own search activities, arguing that the work of organisations searching for the missing is not effective enough.

Families of missing soldiers have faced a shortage of lawyers specialising in military law, resources to obtain legal aid, and a lack of information about the possibilities of obtaining free legal aid and reimbursement of legal services. In addition, psychological help is a pressing need for many families, as they are facing difficult emotional experiences.

New ways of communicating with missing persons’ relatives

Several institutions officially deal with the issues of missing persons in Ukraine. These are the National Information Bureau, the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, and the United Center for the Coordination of Search and Release of Prisoners of War at the Ukrainian secret service. They officially receive information relating to Ukrainian prisoners from Russia through the International Committee of the Red Cross.

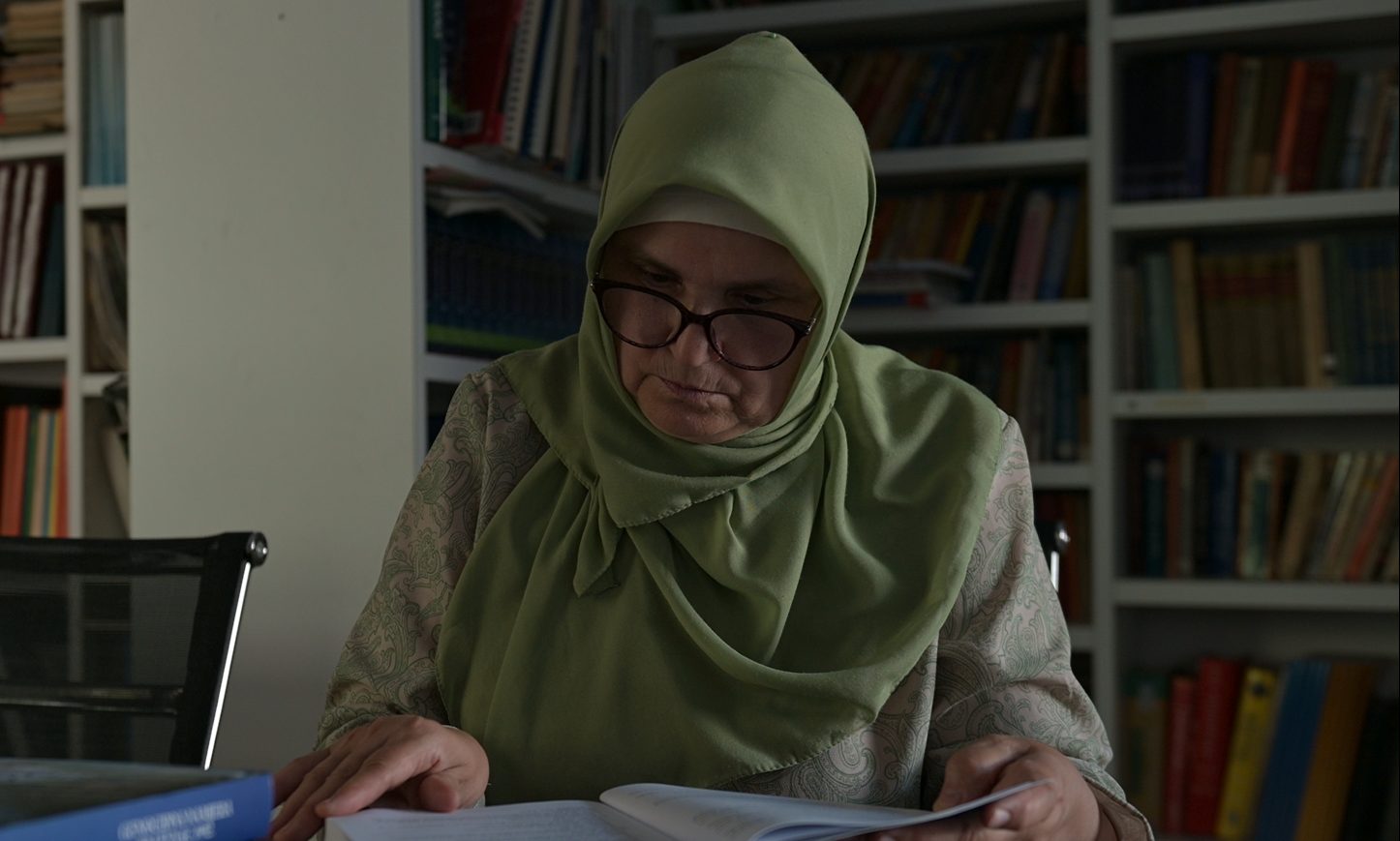

The Network of Regional Representatives of the Interior Ministry’s Commissioners deals with matters concerning persons who went missing under special circumstances. In the Chernihiv region, the regional representative is Kateryna Smurygina, a lawyer with over 15 years of experience in the public and private sectors.

Smurygina says that she wants to help families of the missing as much as possible, and that is why she holds field meetings in communities in the region almost every week and communicates directly with families. The Chernihiv region has become a pilot region in the country where this format of work has begun to be implemented.

According to Smurygina, in early November, 1,502 people who went missing under special circumstances were registered in the Chernihiv region. She says her database is formed on the basis of relatives’ reports to the police, although it does not separate soldiers from civilians. Information about the military is labeled ‘restricted access’.

The case of a person’s disappearance is handled by an investigator in the location where the disappearance happened. The task of searching for missing persons in Ukraine is entrusted to the police.

Smurygina says area police departments have special ‘search centres’ that are in contact with relatives of missing persons. “This has reduced the number of questions for investigators. My families have complained about the frequent replacement of investigators, but someone quits, someone moves to another job, someone is mobilised, and someone, unfortunately, dies – this is the reality of our life,” says Smurygina.

Families of the missing are subjected to scams

Obtaining an extract from the Single Records of the Missing under Special Circumstances, in order to confirm the status of a missing relative, is an important issue for families. The request can be filed electronically, but the extract itself can only be obtained with documentation provided by a relative. For civilians, it is necessary to prove joint residence in court and for ex-wives, they will be able to obtain a copy of the extract if they are legal representatives of children they have together with the missing person.

On the basis of information from the registers, families can receive an allowance for children, after losing ‘the breadwinner’ of the family.

Smurygina says that one of the things families of the missing need more is psychological support. “We partially perform this function. Often, in order to answer a question, you first need to listen to the person and their feelings, and calm them down a bit,” she said.

They are currently creating ‘sustainability centres’ in the region, which include a social worker who is in contact with families of the dead, prisoners and missing persons. But so far, these centres have not been avalaible in all communities.

“Sometimes I ask families more substantial psychological support. And if the person agrees, then I give them contacts of public organisations working in that area,” Smurygina says. She adds that all services related to examinations and legal aid to families of missing persons are free of charge.

Fraudsters who target families of the missing are another problem they face. When families share detailed information about their relatives – such as a photo, date of birth, rank, military unit, or indicate the exact location of their disappearance – scammers can take advantage of this. Most often, families receive calls asking for payment for services that are normally free, or are offered the chance to communicate with missing loved-ones for a fee. Sometimes such calls come from Russia, which seem genuine, and encourage relatives to trust the scammers.

A search that will never end

Ukraine can benefit from the experience of countries that have survived modern wars, such as Kosovo and Bosnia & Herzegovina.

Kosovo forensic expert and professor Arsim Gerjaliu believes that Ukraine needs to learn from others so as not to repeat their mistakes.

Gerjaliu says that 13,553 people went missing before the end of the war in Kosovo, and 1,600 are still being searched for. Most of the people who disappeared in Kosovo during the war have been identified in mass graves.

As he explains, two commissions from Serbia and Kosovo that worked on the return and identification of bodies of the dead continued to hold regular meetings. He says around 1,000 dead people have been returned from the territory of Serbia, and that some Albanians who were considered missing were imprisoned and returned home alive.

According to Gerjaliu, in the search for missing persons, all information is important – appearance, special marks, clothing, who saw them last and where. He believes that after the war in Ukraine, it will be useful and necessary to collect detailed information in all settlements that were under occupation in order to establish a complete list of the missing.

In addition, he points out that the country in which there was a war should lead and coordinate this process.

“A lot has been done in Kosovo thanks to the support of partners, but you (Ukraine), not someone else, should control the whole process. It is important to be the leader of this process and not skimp on the training of domestic specialists,” he says.

Gerjaliu thinks that working on preserving the memory of the past is equally important. Commemoration is an integral part of post-war life, because if the dead and missing are not remembered, the war crimes committed are more likely to be repeated.

However, despite searching, sometimes the information, or the missing person, is never found. “The hardest part is at the end of the search, when the fate of most of the missing has already been determined. After all, over time, witnesses can die, and evidence can be lost. Unfortunately, it will not be possible to find all of them and find out all the circumstances of their disappearance.”