This post is also available in: Bosnian

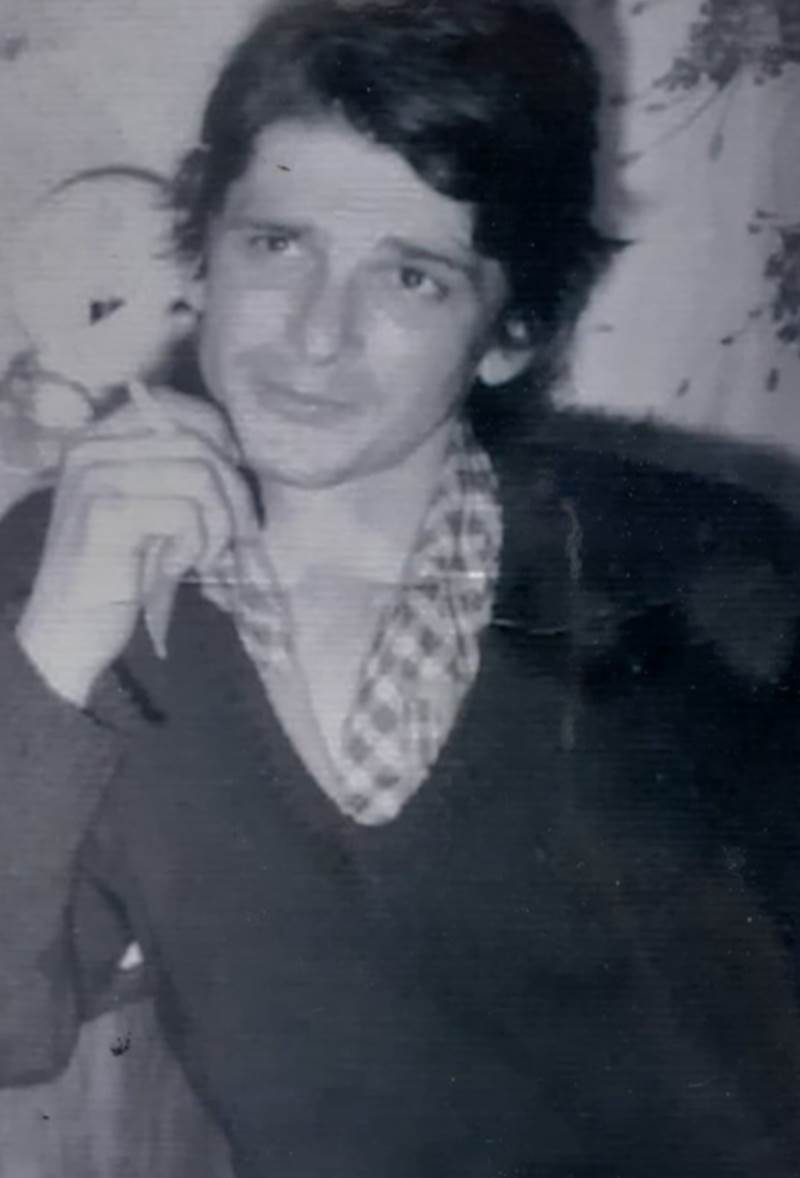

Dzenana Salihovic. Photos courtesy of Dzenana Salihovic.

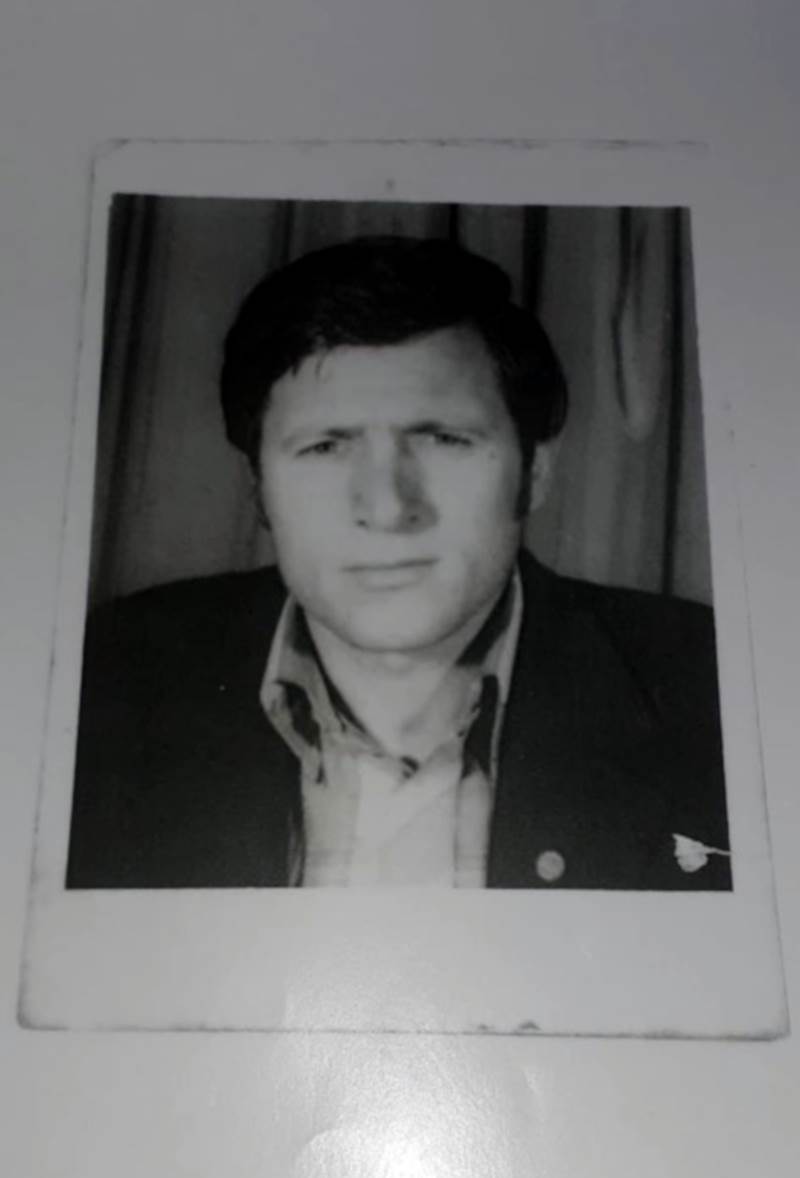

Dzevad Salihovic. Photos courtesy of Dzenana Salihovic.

“In July 1995, my mother managed to get me and my sisters Nevzeta, Nihada and Dzevada out of Srebrenica, but nothing else, not even a picture of my father. It was not until I was five that I saw him for the first time. I was too little to understand why he was gone,” Salihovic said.

According to Srebrenica victims’ associations, Salihovic is one of 205 children from the eastern Bosnian town who were born in the days before the genocide or after their fathers were killed by Bosnian Serb forces who seized Srebrenica 25 years ago this week.

Salihovic’s family left Bosnia and Herzegovina but she returned to live in Srebrenica with her mother Ramiza and her sisters in 2002. She has a master’s degree in sociology and now works with the Srebrenica Memorial Centre, investigating the genocide and collecting items and archive documents that relate to the mass killings of more than 7,000 Bosniak men and boys in July 1995.

She said her mother and other relatives have told her about her father’s last words before he joined thousands of other men from Srebrenica who tried to escape from the Bosnian Serb Army and police by fleeing through the woods towards Bosniak-controlled territory in Tuzla.

“My mother told me he gave her cookies and told her and my sisters to take good care of me. I was just over a month old,” she said.

‘I hoped he would appear from somewhere’

Salihovic’s father was captured and then killed along with hundreds of other men at an agricultural warehouse in Kravica, one of a series of massacres of Bosniaks that international courts have classified as genocide.

His body was found near Zvornik in 2005. Salihovic said she remembers the day the news arrived well.

“I came back home from school. Everybody was crying. Up until then I had hoped, as a little girl, that he would appear from somewhere. I hoped I would see my father alive, like lots of other children,” she recalled.

“It was only then that I realised that I would never even hear his voice. As a child, I remember that everybody was crying in our house all the time. I did not realise why he was gone. I do not remember his physical appearance, his voice…”

She said that people who used to know her father say that she resembles him.

“Apart from physical appearance, they say that we have the same personality. I get angry quickly, but it all passes quickly too,” she explained.

Her father, like other Srebrenica victims whose remains have been found and identified, is buried at the Memorial Centre.

“I visit his grave at least once a week. I say a prayer and I feel some kind of consolation. I feel it is easier for both me and him,” she said.

Apart from the pain caused by growing up without her father, she is also saddened by the fact that 25 years on, the Srebrenica genocide, the worst atrocity in Europe since World War II, is still being denied.

“This town has no future until everyone has faced up to the past. An honest confrontation is the only way forward,” she said.

The authorities in Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Republika Srpska entity, where Srebrenica is located, do not accept that the 1995 massacres constituted genocide – a stance that is shared by the authorities in Serbia. Glorification of war criminals and genocide defendants like Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic remains commonplace.

“Unfortunately, in Srebrenica we often see posters and murals dedicated to our fathers’ murderers… I often wonder what kind of a person would glorify the murderer of someone’s father,” Salihovic said.

As well as her father, she also lost her grandfather, four uncles, four nephews, an aunt, a grandmother and many distant relatives in the genocide.

Munira Subasic, the head of the Mothers of Srebrenica and Zepa Enclaves war victims’ association, said the hardest thing for her is when people like Salihovic, children of Srebrenica who lost a parent in July 1995, come and ask her for a photo of their father.

“That really is unbelievable. Imagine a child coming to the association’s premises and asking you just to give them their father’s photo to look at,” Subasic said.

“They do not even have that as a memory of their fathers. It breaks your heart.”

‘My father and brother were killed together’

Salko Malagic. Photos courtesy of Amela Malagic.

Amela Malagic. Photos courtesy of Amela Malagic.

It was 2008 when Amela Malagic lost all hope that her father Salko would appear at her door and that she would run into his arms.

“I was in the sixth or seventh grade. I remember we had guests. A phone rang and my mother told me to answer it. The call came from Tuzla or Visoko, I do not remember. I was told that they had found the bones of my father Salko and my brother Elvir, who were killed together,” Malagic recalled.

“As a child, up until then I had hoped they would appear from somewhere. My brother Admir was also killed, but his remains had been found and buried earlier. Then I realised I would never see them. Up until then, I had hoped to hug my father.”

Malagic was born in Tuzla in January 1996. Her mother Mirsada, arrived there while pregnant after having managed to flee Srebrenica in July 1995 with her then nine-year-old son Adnan.

Malagic said the pain caused by her father’s death is so great that she has never enquired where and how he was killed. His bones were discovered in six so-called ‘secondary graves’, where some Srebrenica victims’ bodies were moved after their initial burial as part of attempts to cover up the massacres. Many bodies were broken up in the process.

“He was found in Kamenica in Zvornik. The cause of death is unknown, because his body was dismembered and put into six graves,” Malagic said.

“My brother Admir was shot dead. He was also found in Kamenica, while Elvir, who was 22, was found in four secondary graves in Kamenica.”

She has never stopped missing all of them.

“All the things I should have had as a girl and now as a woman are missing because someone brutalised my father and brothers,” she said.

“I have painful memories of Srebrenica. I go there as often as I can. At least I know where they are, they have a grave… I go there and cry it all out.”

The first time she realised that her upbringing was different from that of other children of her age was when her mother Mirsada, who was injured in Srebrenica in July 1995, went to the Hague Tribunal to appear as a witness. She testified at the UN war crime court four times.

“Mum was one of the key witnesses at the trials of Ratko Mladic, Radislav Krstic and Zdravko Tolimir. Her testimony was one of the key testimonies for proving what kind of crimes they committed, for which they have been sentenced,” she said.

Malagic herself went to see one of the hearings in Mladic’s trial at the Hague court.

“I was a high school kid and already aware of all that. I know he provoked the witnesses, he was arrogant and made himself a victim,” she recalled.

“Honestly, I do not hate him or those like him. All of them will answer for their crimes and get what they deserve from the God. They changed my life completely, even before my birth.”

‘I miss him all the time’

Amir Secic. Photo: BIRN BiH

“All kids have a dream. I had one too. I dreamed I would get to meet my father one day. My father, about whom I have heard so many stories, but have never seen or heard his voice. His name was Ibrahim…”

These are lines from a book entitled ‘I Was Hardly a Child’ by Amir Secic, dedicated to his father, who was killed in the Srebrenica genocide.

Secic was born in Tuzla in October 1995. Three days after his birth, his mother abandoned him at a children’s home, where he spent the next 20 years.

After his book was published, he began to receive calls from relatives of his father who he did not know before.

He recently met one of them, a cousin who lives in the United States and who confirmed that one of his dreams about his father Ibrahim being a fan of a German football club was true.

“I dreamed that my father was a Borussia Dortmund supporter. He often comes to me in my dreams and that’s how I’ve created an image of him. The cousin from America, who I asked what Ibrahim was like and whether he liked football, told me a couple of days ago that my father really was a Borussia supporter,” Secic said.

His father’s remains were found in a mass grave in Zeleni Jadar, not far from Srebrenica, in 2010. But Secic did not attend the collective funeral at the Srebrenica Memorial Centre, where his father was buried in 2013.

“The educators did not want to upset me. They wanted me to avoid any more suffering,” he said.

Like Amela Malagic, Secic often visits Srebrenica.

“I go there whenever I can, but I have to prepare myself mentally, because each visit to Srebrenica means confronting what I keep deep inside of me again,” he said.

He misses his father all the time, he continued, but most of all on his birthday and on the Muslim festival of Eid.

“I missed him seeing all my successes in school,” he said. “There was no one I could show my school report card with ‘A’s in it. No one was there to stand behind me and have a photo taken together with me holding the report card.”