This post is also available in: Bosnian

Samir ‘Bowie’ Mehic wrote the lyrics of this song, entitled ‘Absurd’, in Srebrenica during the war. At that point, the town was being besieged by Bosnian Serb forces; its residents were suffering from food and water shortages, and they had no idea what would happen next.

During the siege, guitarist Mehic, who was nicknamed Bowie for his love of the iconic British singer, worked on his guitar skills. He also fell in love, got married and found out that he was going to be a father.

In the end, however, he was destined to share the tragic fate of thousands of others from Srebrenica. When Bosnian Serb troops and police overran the town in July 1995, he joined the exodus of desperate men and boys who tried to escape death by fleeing through the woods to safety.

He handed over his notebook with his lyrics and some photographs to his wife Nermina when they parted, and then she never saw him alive again.

‘Music was always playing’

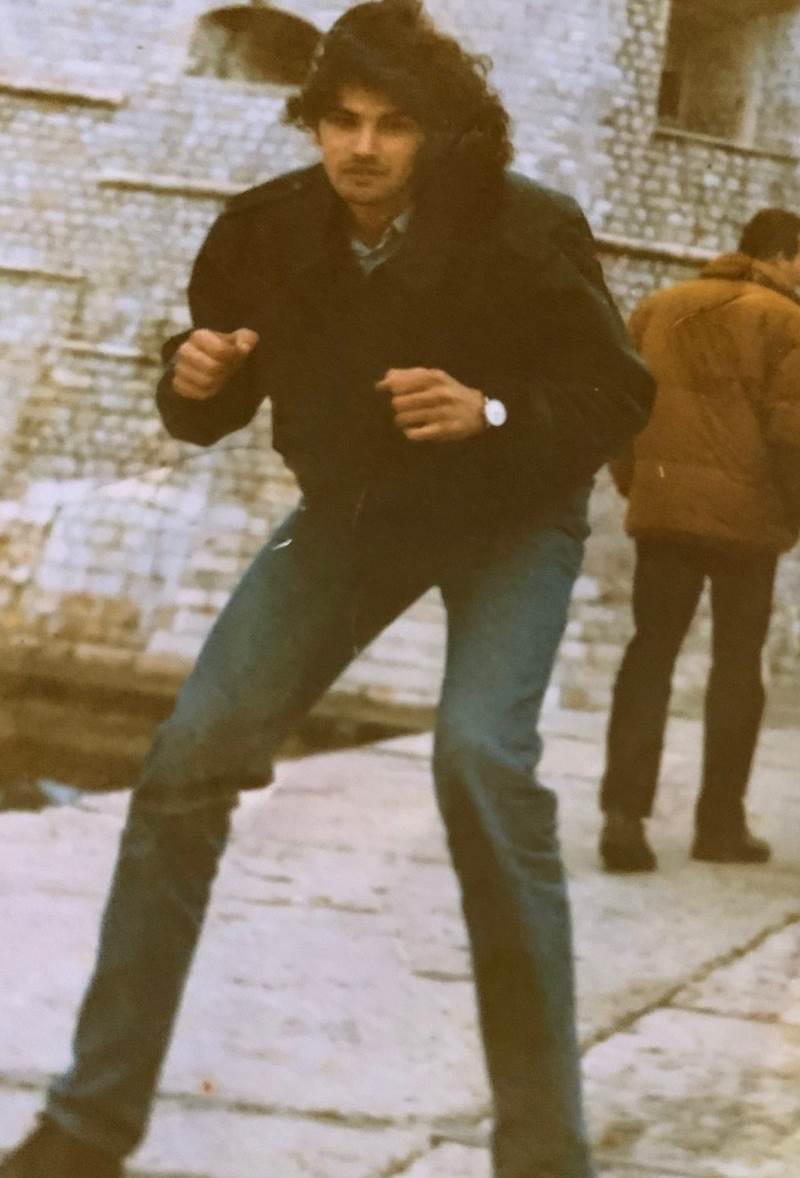

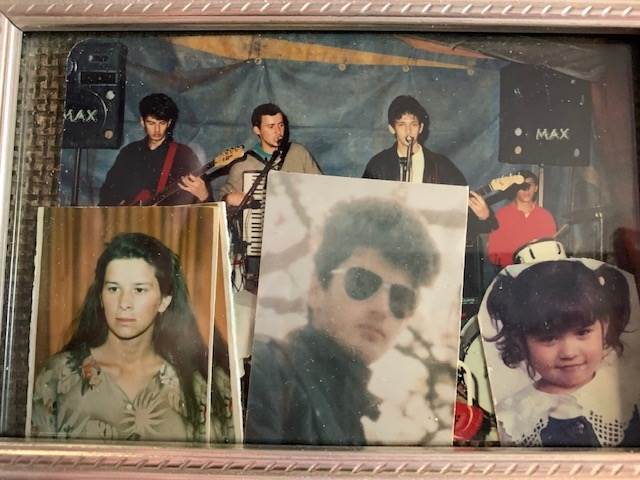

Samir Mehic. Photo: Family album

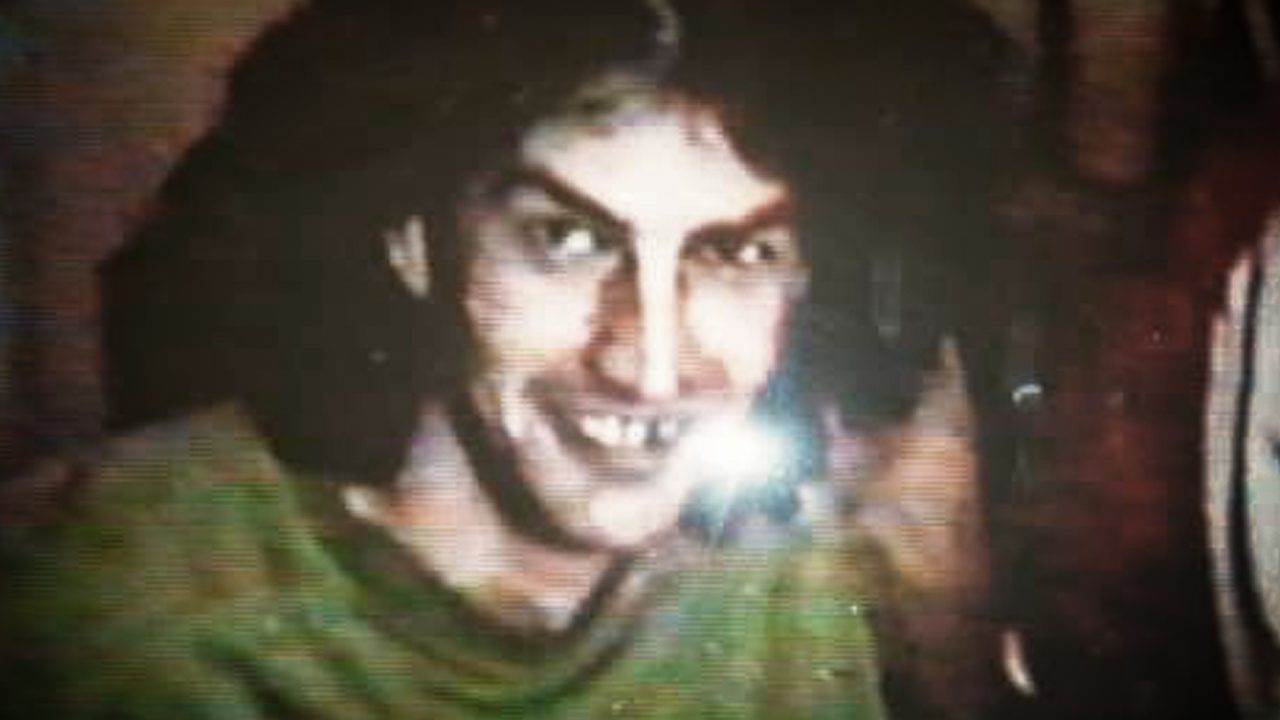

Samir ‘Bowie’ Mehic. Photo courtesy of Faruk Smajlovic.

Twenty-five years later, as the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide is marked this week, Mehic’s friends and relatives still remember him fondly – as a dedicated musician and a good man.

He was well-known in Srebrenica – the town’s favourite rocker, born in 1967, with strong features and thick, long hair who was always listening to or playing music.

“When you didn’t hear music, it means he was either not at home or sleeping. There was no other possibility,” said his sister Selma Rajkic.

“The first thing he did when he got up in the morning wasn’t to wash his face, but to turn the music on, the cassette player or the stereo, and then wash his face and have breakfast. Music was always playing while he was awake.”

Samir ‘Bowie’ Mehic. Photo courtesy of Faruk Smajlovic.

She remembers her brother as a sociable person, whose small room was always full of friends. Music had been his passion since his childhood, she said.

She also remembers Bowie babysitting her son Semir when he was a baby.

“He would play and Semir would keep calm, listening. He would play for an hour, and the child would fall asleep like that,” Selma said, adding that her son now looks very much like her brother, and also plays guitar.

Her husband Suad Rajkic remembers meeting Bowie after he had married Selma.

“I grew up in a big family. My father and mother were very strict and we had to obey, while they seemed unreal to me, Samir particularly so,” he recalled.

“I would come and he would put some loud music on. It was their family house, and the walls were falling down,” he said, laughing.

He pauses to wipe away tears before going on to say that Bowie of course had a David Bowie poster on the wall of his room.

‘He was special in every way’

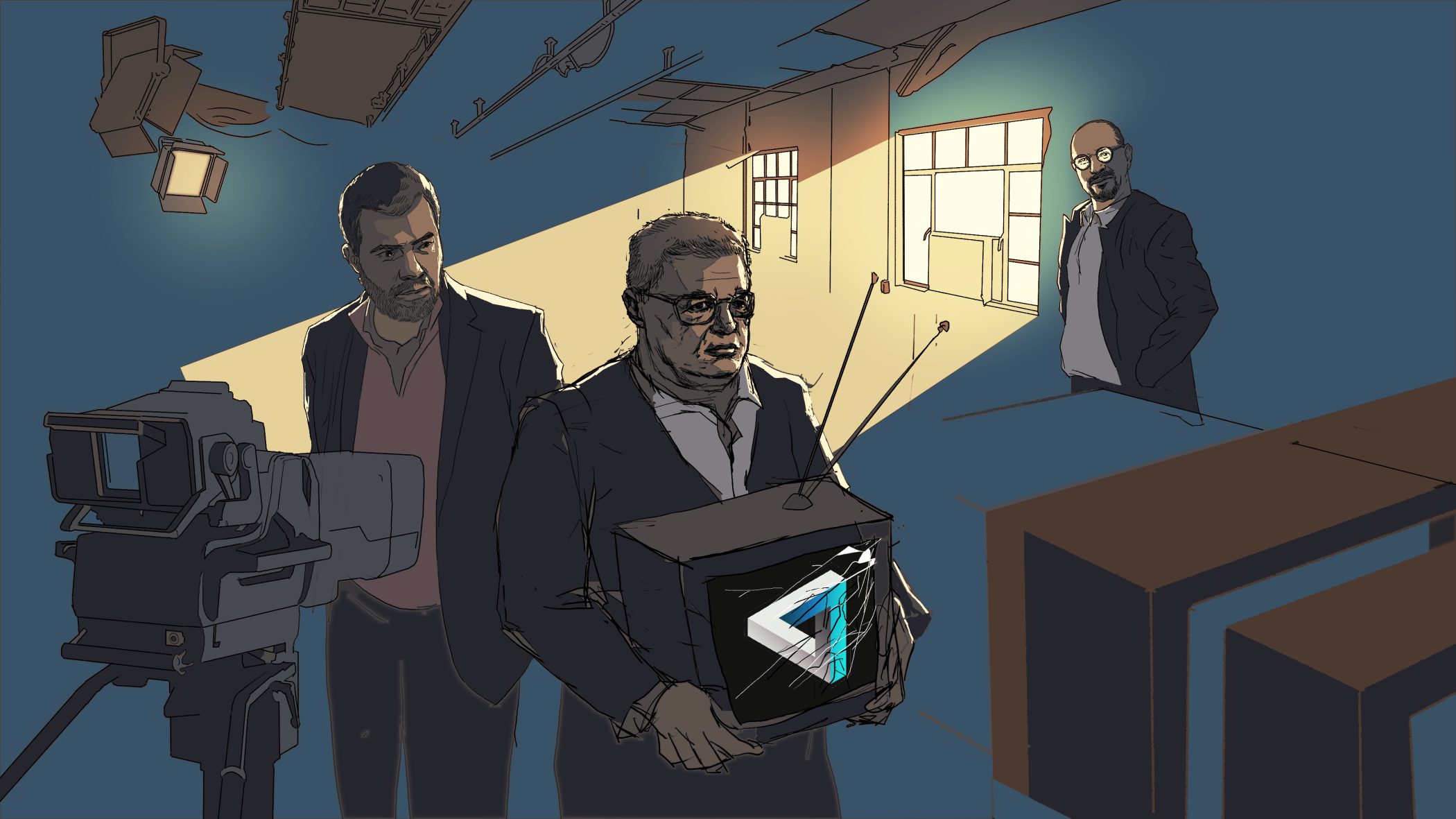

Illustration: Nerma Sofic for BIRN BiH

Faruk Smajlovic met Samir Mehic in the late 1980s when he went to an audition as a drummer. They formed an intense friendship and a band called Inat (Spite), so named because of their dislike of “various people and injustices”, he said.

“We got gigs at some hotels, where we played slow, nice folk songs, but rock’n’roll was in our blood. But we used to sell up to 700 tickets per night for rock concerts at our discotheque in Srebrenica, where we played every weekend,” Smajlovic recalled.

“There are not so many residents in the town of Srebrenica now,” he added.

Smajlovic also shed some tears as he talked about his friend and what he represented in pre-war Srebrenica.

“Samir Mehic Bowie was a special person, particularly in my life,” he said.

“He was special in every way, in the way he behaved. He was out of the time we lived in.”

He got the nickname Bowie because he was one of the first people in Srebrenica who listened to David Bowie, Smajlovic continued.

“He was the first one from that generation who inculcated good music in us – psychedelia, good-quality rock,” he said.

“I think he should not have been born in Srebrenica. He should not have been born in Bosnia. I am sure he would have made a great career had he lived somewhere else.”

Smajlovic left Srebrenica in April 1992 after attacks by Bosnian Serb forces started in the area and the war began to intensify. Many of his other friends moved away from Srebrenica too, but not Bowie. He stayed.

“I have to say I’m sorry that we left him here in the lurch. He was the only one from our crew who stayed here,” Smajlovic said.

“I can imagine how he felt, how he went through that, and then, amidst all the misery and suffering, he started practicing guitar-playing intensively. He started playing classical music. They say he improved so much that it was unbelievable.”

During the war, he formed a new band in Srebrenica, called Absurd like his song, and cut his hair short. In the third year of the conflict, he also fell in love.

He married in 1995, and he and his wife Nermina Mehic soon discovered that they were going to have a child.

“He was very excited to learn that he would become a father. He used to say that he could hardly wait to become a father. Unfortunately, he did not live to see it,” said Nermina, who now lives in the United States.

‘See you, God willing’

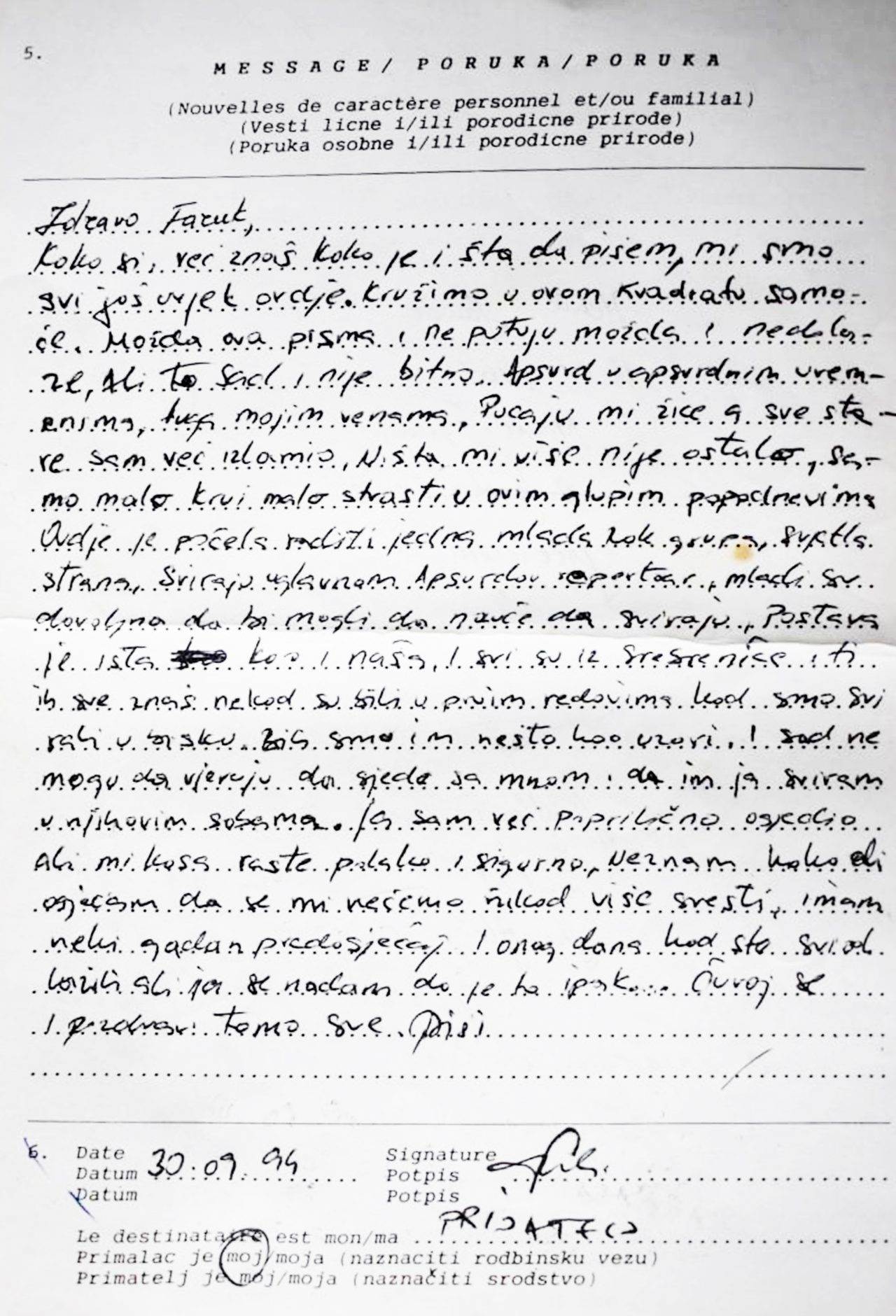

In September 1994, Samir Mehic sent a letter to his friend Faruk Smajlovic:

Mehic letter to a friend Faruk Smajlovic. Photo: Srebrenica Memorial Center

“Dear Faruk, how are you doing? You already know how things are and what I’m going to write. We’re all still here. Going round in this square of loneliness. These letters may go anywhere and may not be reaching you, but that’s not important now. Absurdity in absurd times, sadness in my veins. My strings are breaking, and all the old ones are already broken. I have nothing left during these stupid afternoons but some blood, some passion.

“This is the bright side – a young rock band has begun playing here. They mainly play the Absurd’s repertoire. They’re young enough so they can learn to play. All of them are from Srebrenica, just like us. You know all of them. They used to stand in the front rows at our gigs. We were something like role models to them. Now they can’t believe they’re sitting with me and I am playing for them in their rooms. My hair is already quite grey now, but it is still growing slowly and steadily. I don’t know why, but I feel like we will never meet again. I have some kind of ugly premonition. And I had it on the day when you were all leaving, but I hope that – well, who knows… Take care and say hello to everyone there. Stay in touch.”

Left to right: Nermina Mehic, Samir ‘Bowie’ Mehic and their daughter Samra. In the background, Mehic’s band Absurd playing live circa 1993. Photos courtesy of Nermina Mehic.

When Bosnian Serb forces finally decided to seize Srebrenica in July 1995, Samir and Nermina Mehic, along with her brother Selim Selimovic, fled the town with the other local Bosniaks on July 11, 1995.

“Because I was pregnant, I got sick at the first bend in the road, I was anaemic. Samir took me back. He just grabbed me by my shoulders and said: ‘Nermina, you must go,’” she recalled.

“So, I decided, against my will, to listen to him and leave. As we parted, he just gave me his notebook and a couple of photos and said: ‘Take these, you’ll look after them better than me. See you, God willing.’ That was the last thing he said.”

She returned to Potocari near Srebrenica, and the following day she was put on a bus by Serb forces transporting Bosniak women and children to Tuzla, which was under the control of the Bosniak-led Bosnian Army.

She recalled that on the road between Bratunac and Konjevic Polje, when the buses stopped, she heard shooting in a place called Kravica, and got up from her seat to see what was happening.

“I saw so many people on the right-hand side…. I stood up with the intention of getting out and not going any further if I saw either of them,” she said, sighing deeply.

She still finds it hard to talk about what happened to her husband and brother.

“It is distressing, but I’m trying to say as much as I can. It is hard even though 25 years have passed; it is always hard, not only today,” she said.

Bowie’s family and friends have heard various stories about what happened to him. They were told that he was injured along the way and had to stop walking. His sister Selma said that she heard that he told some friends who were also fleeing to keep going while he sat down to rest because his legs hurt.

Nišani Samira Mehića i njegovog oca Fuada. Izvor: Faruk Smajlović

What is clear is that he was captured and killed, like more than 7,000 other Bosniaks from Srebrenica who were murdered by Bosnian Serb forces in a series of massacres in July 1995 that have been classified as genocide by international courts.

His remains had been broken up and were found in two different graves – the same graves in which his father Fuad’s remains were also found.

Smajlovic said that Bowie’s coffin had the number 501 – a symbolic number, he said approvingly, because his friend liked Levi’s 501 jeans.

“These are strange things – sometimes you are happy to bury someone, because it simply means they have found peace, and you know where they are, where you can go to say a prayer for the dead,” Smajlovic said.

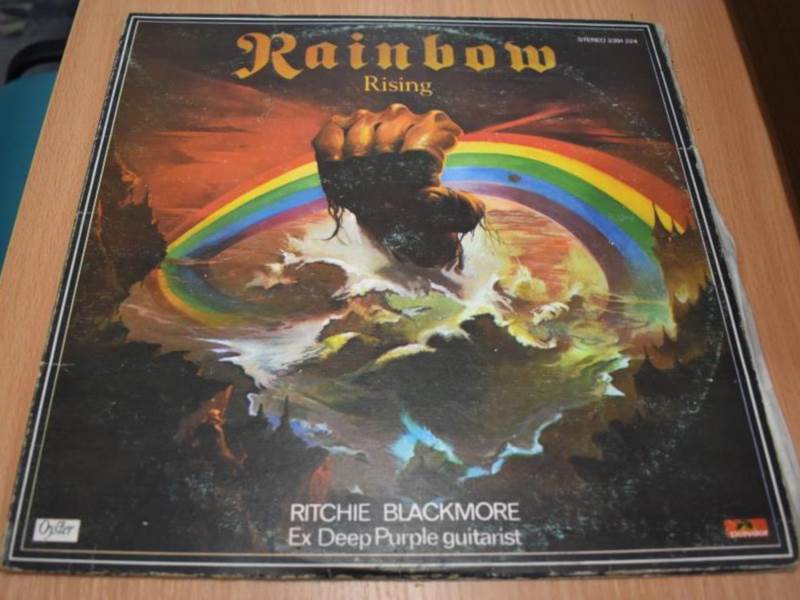

Mehic record. Photo: Srebrenica Memorial Center

Mehic record player. Photo: Srebrenica Memorial Center

He kept Bowie’s stereo and the records that were found in his house after the genocide for years, alongside a letter that his friend sent him back in 1994. He recently donated them to the Srebrenica Memorial Centre so they could be put on display.

“My mission is to make sure he will not be forgotten,” he explained. “I always say that through Samir, we can see all the other victims.”