This post is also available in: Bosnian

In a recent international operation staged by Interpol to break up a ring of people involved with child sexual abuse material created using artificial intelligence, 25 people

In a recent international operation staged by Interpol to break up a ring of people involved with child sexual abuse material created using artificial intelligence, 25 people were arrested in several countries – one of them in Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The suspect is believed to be one of several hundred people worldwide who had subscribed to receive images produced by a Danish citizen with the help of artificial intelligence tools.

There are no real children in the videos, but the European police agency Europol is clear that possessing or sharing such recordings represents a criminal offence.

In a video released by Europol, investigator Danny van Althuis explained that selling child abuse material on social media was a genuine crime.

“We know that the artificial intelligence models are trained on real child abuse material, so AI generated images always have a link to real children being abused,” Althuis said.

The police in the Republika Srpska entity confirmed to Detektor that photo and video material was found in the possession of the person arrested in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that some of it was generated with the help of tools based on artificial intelligence. However, the police said that they still have work to do to uncover the real-life victims.

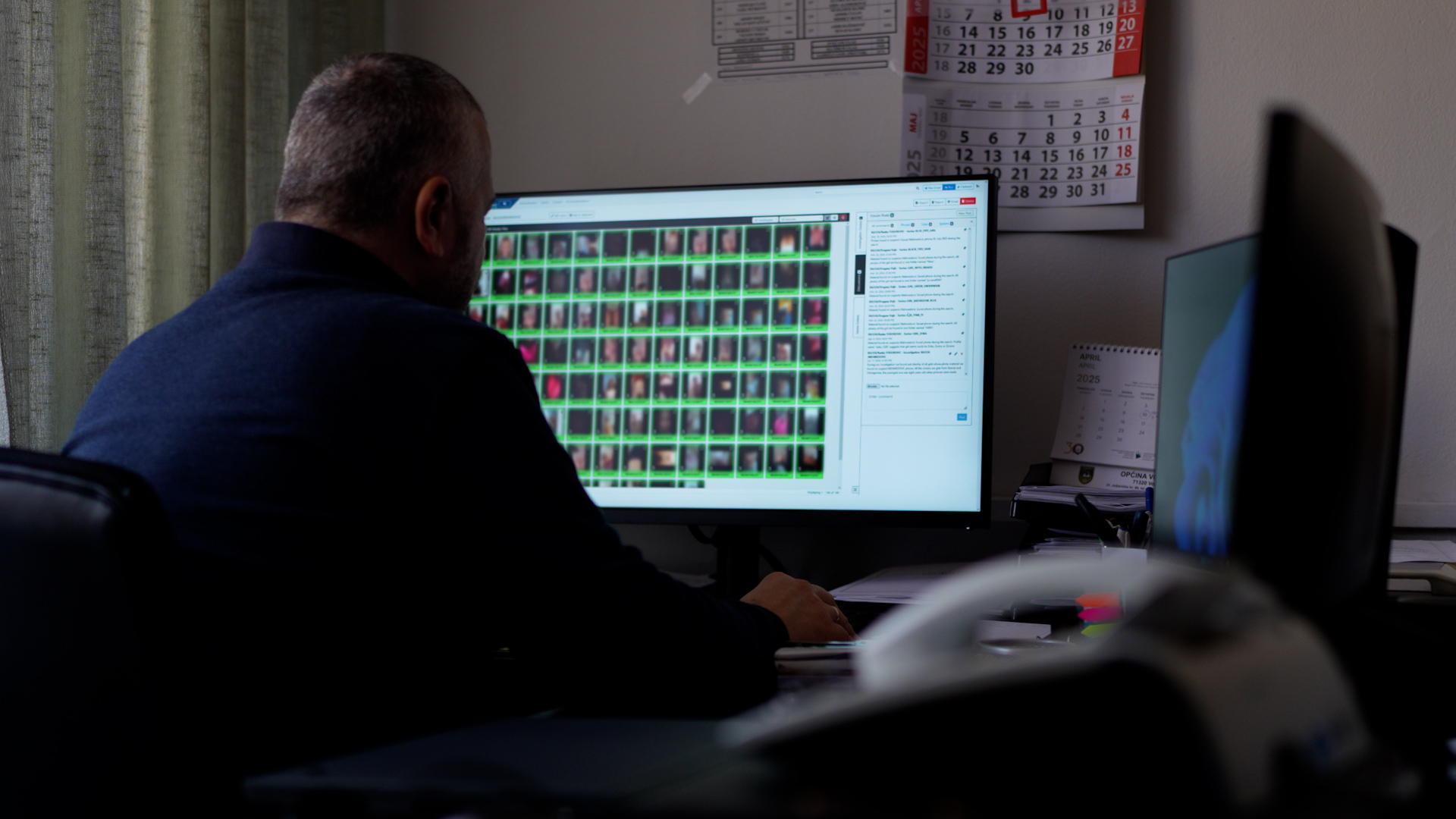

Olivije Zimonja, the head of the entity police’s High-Tech Crime Unit, considers this one of the priorities of the investigation. The force is making use of the databases of international police agencies Interpol and Europol.

Zimonja said that the tools available to the police to detect AI-generated content are still in development, and their accuracy and applicability have still not been fully developed.

People who make such recordings use images of children taken from parents’ posts on social media, which they publish in ignorance of possible risks, he explained – “not having a clue that a photo of their child could be abused”.

The police agency in the Federation entity also says that it has encountered videos created with the help of artificial intelligence in which children are abused.

Eneid Hasanovic, head of the team for combatting child abuse on the internet at the Federal Police Directorate, explained that body parts from photographs that were publicly available were used to create the material.

“Usually, they use the face of the person being depicted to generate the material showing sexual abuse,” Hasanovic said.

Sanctioning a perpetrator in Bosnia and Herzegovina may be more difficult than finding them because of differences in legislation between countries, but also because this is a relatively new and unknown challenge.

The Criminal Code of Republika Srpska recognises the exploitation of children for sexual abuse images and introducing children to pornography as a criminal offence. Zimonja said that the way the law is written conforms with international standards.

“The emphasis is on protection even in cases where a ‘non-existent child’ is shown,” Zimonja explained.

In Brcko, the Criminal Code also provides for a possibility of prosecuting child abuse through content modification, explained Sarajevo Cantonal Prosecutor Darko Soldat, who holds a master’s degree in digital forensics and high-tech crime.

“There is an urgent need to invest in programmes for police authorities that will have investigative and forensic functions,” Soldat said.

In the Federation, legislation has not been properly updated to punish child abuse on the internet, said several experts interviewed by Detektor.

Nineta Popovic, head of the communications section at the UN child protection organization UNICEF’s office in Bosnia and Herzegovina, believes that it should make no difference whether a child’s rights are violated in the real or online world.

“A crime is a crime, regardless of whether it happens online or offline. These are the key messages from UNICEF as well. If we talk about online violence, we must not treat any of its aspects differently from violence happening in real life,” she says.

Popovic argues that legislation must be updated to follow developing trends in criminal activity.

Helping children protect themselves

Since the Banja Luka-based Nova Generacija Association launched its Blue Phone counselling line, it has received nearly 70,000 calls.

Maja Kovacevic is a counsellor for Blue Phone, which has registered cases of children and young people sharing their intimate photos with people they met on the internet.

“After a while, harassment starts – threats and blackmail – and then the children come to us to get help and support, because they are not sure how to act in such situations, how to protect themselves,” Kovacevic says.

Tatjana Makric works with children at the Day Centre for Children at Risk. Lately, she has noticed the growing abuse of artificial intelligence to create fake information that was posted by young people in chat groups in primary schools in Banja Luka.

“They shared information that was completely incorrect,” says Makric.

The Blue Phone service was set up to provide support to children, but also to parents.

Kovacevic says that it is important for children to know that they are not alone when facing violence.

“If they’re suffering in some way, or have mental health issues, they should know that it’s OK to seek help and support; that it doesn’t mean that they’re weak, but on the contrary, that they’re brave and that there is really someone who cares about how they’re feeling and what they’re going through,” she says.

were arrested in several countries – one of them in Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The suspect is believed to be one of several hundred people worldwide who had subscribed to receive images produced by a Danish citizen with the help of artificial intelligence tools.

There are no real children in the videos, but the European police agency Europol is clear that possessing or sharing such recordings represents a criminal offence.

In a video released by Europol, investigator Danny van Althuis explained that selling child abuse material on social media was a genuine crime.

“We know that the artificial intelligence models are trained on real child abuse material, so AI generated images always have a link to real children being abused,” Althuis said.

The police in the Republika Srpska entity confirmed to Detektor that photo and video material was found in the possession of the person arrested in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that some of it was generated with the help of tools based on artificial intelligence. However, the police said that they still have work to do to uncover the real-life victims.

Olivije Zimonja, the head of the entity police’s High-Tech Crime Unit, considers this one of the priorities of the investigation. The force is making use of the databases of international police agencies Interpol and Europol.

Zimonja said that the tools available to the police to detect AI-generated content are still in development, and their accuracy and applicability have still not been fully developed.

People who make such recordings use images of children taken from parents’ posts on social media, which they publish in ignorance of possible risks, he explained – “not having a clue that a photo of their child could be abused”.

The police agency in the Federation entity also says that it has encountered videos created with the help of artificial intelligence in which children are abused.

Eneid Hasanovic, head of the team for combatting child abuse on the internet at the Federal Police Directorate, explained that body parts from photographs that were publicly available were used to create the material.

“Usually, they use the face of the person being depicted to generate the material showing sexual abuse,” Hasanovic said.

Sanctioning a perpetrator in Bosnia and Herzegovina may be more difficult than finding them because of differences in legislation between countries, but also because this is a relatively new and unknown challenge.

The Criminal Code of Republika Srpska recognises the exploitation of children for sexual abuse images and introducing children to pornography as a criminal offence. Zimonja said that the way the law is written conforms with international standards.

“The emphasis is on protection even in cases where a ‘non-existent child’ is shown,” Zimonja explained.

In Brcko, the Criminal Code also provides for a possibility of prosecuting child abuse through content modification, explained Sarajevo Cantonal Prosecutor Darko Soldat, who holds a master’s degree in digital forensics and high-tech crime.

“There is an urgent need to invest in programmes for police authorities that will have investigative and forensic functions,” Soldat said.

In the Federation, legislation has not been properly updated to punish child abuse on the internet, said several experts interviewed by Detektor.

Nineta Popovic, head of the communications section at the UN child protection organization UNICEF’s office in Bosnia and Herzegovina, believes that it should make no difference whether a child’s rights are violated in the real or online world.

“A crime is a crime, regardless of whether it happens online or offline. These are the key messages from UNICEF as well. If we talk about online violence, we must not treat any of its aspects differently from violence happening in real life,” she says.

Popovic argues that legislation must be updated to follow developing trends in criminal activity.

Helping children protect themselves

Since the Banja Luka-based Nova Generacija Association launched its Blue Phone counselling line, it has received nearly 70,000 calls.

Maja Kovacevic is a counsellor for Blue Phone, which has registered cases of children and young people sharing their intimate photos with people they met on the internet.

“After a while, harassment starts – threats and blackmail – and then the children come to us to get help and support, because they are not sure how to act in such situations, how to protect themselves,” Kovacevic says.

Tatjana Makric works with children at the Day Centre for Children at Risk. Lately, she has noticed the growing abuse of artificial intelligence to create fake information that was posted by young people in chat groups in primary schools in Banja Luka.

“They shared information that was completely incorrect,” says Makric.

The Blue Phone service was set up to provide support to children, but also to parents.

Kovacevic says that it is important for children to know that they are not alone when facing violence.

“If they’re suffering in some way, or have mental health issues, they should know that it’s OK to seek help and support; that it doesn’t mean that they’re weak, but on the contrary, that they’re brave and that there is really someone who cares about how they’re feeling and what they’re going through,” she says.