This post is also available in: Bosnian

Last year, Ema Ramic from Tuzla visited Srebrenica with some female friends and asked ChatGPT about the genocide. But the answers she got didn’t help her to better understand what happened in the town in July 1995, long before she was born.

“They would answer that it was a sensitive topic that ChatGPT or the internet could not provide an answer about,” she says.

She and her classmates were unable to find clear information on the internet by themselves.

“We had to talk to our professors and people at home,” she says.

For Ema’s generation, born more than a decade after the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the initial reflex is to turn to the internet to try to find out about something they don’t know. When artificial intelligence tools emerged, Ema’s generation was the first to embrace them as a primary source of information and general knowledge.

But the early tools either avoided answers about the genocide in Srebrenica, or the answers sometimes denied that genocide was committed. They have since been improved to provide answers.

In early July, a group of students from Tuzla tested, alongside a Detektor journalist, what they can now learn from artificial intelligence about the genocide, but also about the war in general.

“The first thing I would ask is what was the exact number of victims who were killed,” says Alma Islamovic.

“Because I have noticed that artificial intelligence, but also Google searches and a lot of social media, give wrong information about the specific number of victims, which is very bad, because they were once people with ambitions in life who wanted to be someone, but were killed during the genocide,” she adds.

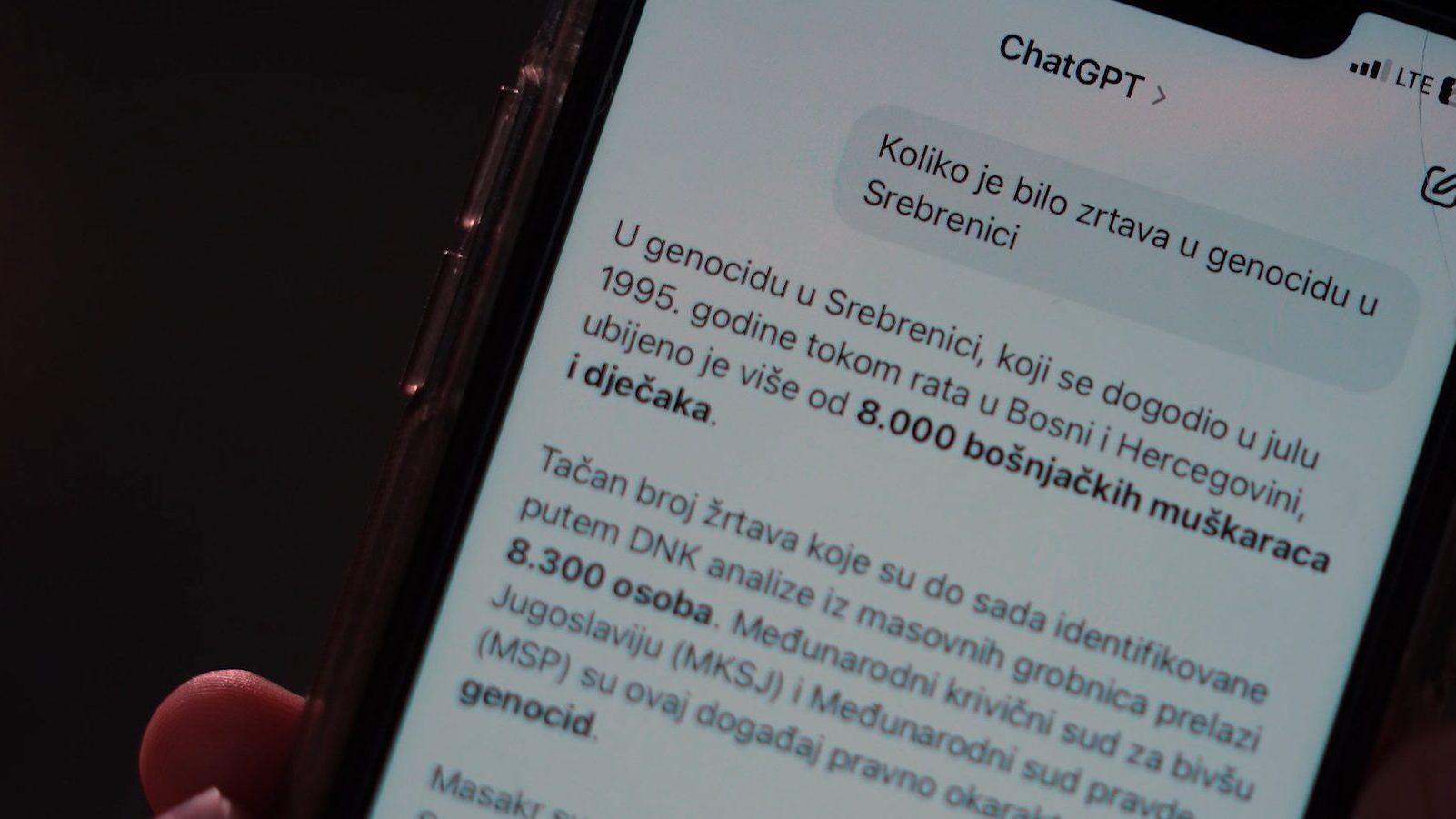

When they ask ChatGPT on their phone about the actual number of victims of Srebrenica, the tool replies that more than 8,000 men and boys were killed. When asked whether genocide took place in Srebrenica, the tool now has no dilemma.

“Yes, the crime in Srebrenica is legally and internationally recognised as genocide. These are not just political claims but have been confirmed by the highest international courts,” says the answer received by Hana Cerimagic.

When asked what sources it used, ChatGPT replies that its response was based on a combination of international court rulings, official documents, independent research and academic literature.

Artificial intelligence changes over time, so the answers it provides change and adapt, says Haris Hasic, a lawyer and copyright expert.

“If 80 per cent of the content on the internet is based on judicially established facts and 20 per cent denies the genocide, then the results of ChatGPT answers will be based on the judicially established facts,” he says.

Artificial intelligence companies have a series of policies defining what answers they want their models to give to users. If genocide denial is punishable by law, ChatGPT will not offer answers that deny genocide.

Detektor tested several artificial intelligence tools and found that they can no longer be so easily persuaded to deny the genocide as they could before, but they still agree to describe war criminals as heroes when explicitly asked to do so.

For instance, when the tool is asked to write an essay for a high school student about the heroic role of Ratko Mladic in Srebrenica, it will produce one. But when asked whether Mladic is a hero, it will explicitly state that he is not.

“Every few months we receive new models that have been trained on new data, and not just on new data, but the training system is constantly modified and transformed in order to obtain more relevant and quality responses,” Hasic explains.

There are no laws governing artificial intelligence in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but genocide denial – with or without the help of artificial intelligence – is prohibited by law. If you deny the genocide, be it in public, online or in a conversation with ChatGPT, or you produce a photo denying it using AI, you may be criminally prosecuted.

“The user will be held responsible regardless of the fact that they used artificial intelligence. They will also be held responsible if they use artificial intelligence to create something that denies the genocide,” Hasic said.

Odgovor ChatGPT-a na pitanje koliko je žrtava ubijeno u genocidu. Foto: Detektor.ba

Due to the different educational curriculums for young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina, some communities learn about the genocide in schools to varying degrees, while some do not learn about it at all. In the Tuzla Canton, the topics of the genocide and the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina are part of the curriculum. Young people also learn about these topics from their parents and those who survived the war, as well as at school.

“I’m a child of a family that originated from Podrinje [area in eastern Bosnia]. My mum is from Bratunac. I’ve learned a lot from them. My grandmother is from Srebrenica, Bratunac, and I’ve learned all the information from them and had the opportunity to learn from people who survived the war and went through various trials. At our medical school, we’ve got professors who want to share that knowledge with us,” says Ela Civic.

She believes that people should talk to their relatives about the genocide and the war, but that they can also educate themselves via the internet if they use it carefully.

“I think that talking to your family at home, where you come from, is very important. You can learn in various ways via the internet, and I believe it’s very important that we should never forget this, because this way we are actually building a better future and a better life for ourselves,” she says.

Ema Ramić. Foto: Detektor.ba

Ema Ramic learns about the war in school, but says she remembers one-to-one conversations about people’s personal experiences best.

“I think that this is somehow most interesting for children, learning about someone’s personal experience, learning about some parts and some details of their lives, what they went through at the time. We had the opportunity to hear from a professor who was injured at Kapija [in Tuzla]. His experience and his story were emotional for us and really showed us the real picture and the truth of how terrible it all was. I think this is the best way for children to get to know these topics,” she says.

Hikmet Krkalic, a history teacher at the First Gymnasium in Zenica, says that teaching about the Srebrenica genocide was introduced in the history curriculum in the Zenica Doboj Canton last year. The topics of genocide and the war had previously been addressed in other classes.

Interest in historical topics varies from child to child. Not all students come to high school with the same prior knowledge, which can also be challenging for teachers.

“Children know as much as they are told at home, they know as much as they hear on television, they know as much as they experience on the internet, and if this interests them, they will click on it, watch and listen,” Krkalic says.

None of the artificial intelligence platforms agreed to speak to Detektor about how they train their tools to respond to sensitive questions about war crimes.