This post is also available in: Bosnian

Savchenko was among the first United Nations peacekeepers to deploy to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the summer of 1992, months into a war that would drag on for the next three years and leave 100,000 people dead. More than 40 of them were killed when mortars struck Markale market on August 28, 1995. The Ukrainian contingent was tasked with investigating; they found that the mortars were fired from positions held by Serb forces in the hills around the city.

“I was in Serb positions once,” Savchenko tells BIRN. “You could see everything from those positions. A soldier was able to fire a grenade and see exactly where it exploded. That was terrible. People were just being killed.”

Savchenko also visited the UN safe haven of Srebrenica, in 1993, where he remembered people “crying from happiness to get food”. Two years later, Srebrenica would fall to Bosnian Serb forces and 8,000 Bosniak men and boys would be massacred in the worst mass killing on European soil since World War Two.

After the war, Savchenko returned to Kyiv and worked as a civil servant. He visited Bosnia again just before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Now Savchenko is once more in uniform, clean-shaven, tall and imposing, a veteran of fighting in the cities of Irpin and Bucha, where Russian forces carried out a massacre of civilians early in the invasion. Tetiana Popovych’s son was among those who went missing during the Russian occupation.

Small and slight, Popovych lives in Bucha and works as a nurse in an outpatient clinic. She was elsewhere when the war began, and only returned to Bucha when it was liberated. Her son, Vlad, was gone. Popovych went door to door, pinned up flyers and got in touch with her son’s friends on social media.

Finally, in April 2022, when Russian and Ukrainian forces began exchanging prisoners, a young man contacted her, saying he had seen Vlad in captivity in Russia. Six months later, she received the first letter:

“Hello dear mom. I’m OK. I eat three times a day and they provide me with medical care. How are you? I hope to see you soon. I love you so much. Don’t worry about me and take care of yourself.”

Two years later, Popovych is still waiting for her son’s return. “Why was he taken away from me?” she asks. “Why can’t I see him?”

In the three decades since the end of the 1992-95 war in Bosnia, scores of people have been convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, both in local courts and at the UN tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ICTY. It was the ICTY that ruled the Srebrenica massacre constituted genocide.

The process has been painstaking and traumatic, and some families are still searching for their loved ones.

Popovych’s 29-year-old son is still alive, but he too is potentially the victim of crimes against humanity – deportation and forcible transfer, for example, or imprisonment, or forced disappearance.

Experts argue that Ukraine should learn from the experience of implementing post-war justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to emulate its successes and avoid its failures.

Concern over trials in absentia

Photographs of Tetiana Popovych’s son, who went missing when Russian forces seized the city of Bucha in 2022. Photo: Detektor

Photographs of Tetiana Popovych’s son, who went missing when Russian forces seized the city of Bucha in 2022. Photo: Detektor

Since the start of the invasion, human rights organisations in Ukraine have been mapping war crimes and prosecutors have opened more than 130,000 cases. It is a mammoth task, not least given the difficulty of actually getting the alleged perpetrators to court.

“If we talk about numbers, as of this morning we have 133,000 incidents,” said Yuriy Belousov, Ukraine’s chief war crimes prosecutor. “Every day there are 300 or 400 new crimes. It’s really on an unimaginable scale.”

Fluent in English, dressed in a black T-shirt and tracksuit trousers, Belousov heads a team of more than 240 prosecutors. They are divided into teams, each tasked with investigating a different set of crimes: genocide, sexual violence, collaborating with the enemy, attacks on civilian infrastructure…

The prosecution has charged 634 people, but only 17 are physically present. Everyone else is being tried in absentia.

Belousov conceded that trial in absentia “has more negative than positive aspects”, but he says it is vital that the victims are given the opportunity to speak and that the crimes committed against them are identified and registered. “Victims want to know that they are not forgotten,” he said.

But the strategy is coming in for criticism.

“The state creates great expectations because it keeps saying that we will have verdicts for all crimes. But this is not true,” said Alena Lunova, an advocacy coordinator at the prominent Kyiv-based rights group ZMINA.

A cafe in Kiev. Photo: Detektor

A cafe in Kiev. Photo: Detektor

“We need to change that, the communication with victims and survivors,” said Lunova, a native of Russian-annexed Crimea. “We must tell them: ‘Yes, we’re going to try to take all action required to bring these criminals to justice. But we can’t promise you that every single one of them will be in court.’”

Sarajevo lawyer Sabina Mehic, who has trained Ukrainian lawyers on the principle of a defendant’s right to defence in war crimes trials, said the convictions risked being overturned.

“They are currently conducting a great number of trials in absentia and according to the information I have, all such verdicts have been convictions,” Mehic told BIRN.

“There is no question that someone can be tried in absentia, but such trials have their own rules. It is necessary to respect those rules and rights, the rights of the accused, so that they don’t end up like some cases in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where all those people were tried again.”

Justice a prerequisite for peace

Oleksandra Matviichuk in her office in Kyiv. Photo: Detektor

Oleksandra Matviichuk in her office in Kyiv. Photo: Detektor

Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Centre for Civil Liberties, which won the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize for its work in promoting democracy and documenting war crimes, said it is crucial that Ukraine – unlike Bosnia – perceive justice as about more than simply trying those guilty of war crimes.

“For some people, justice means seeing perpetrators behind bars. For others, justice means getting compensation, and without compensation, they will feel dissatisfied,” Matviichuk, 41, told BIRN.

“For some people, justice also means a possibility to find out the truth about what happened to their loved ones. For others, justice means a possibility to hear and get a public recognition that something that happened to them and their loved ones is not just immoral, but also illegal.”

What Ukraine needs, she said, is a “comprehensive justice strategy in order to meet all these needs”.

“For me, justice means giving people back their names because the war has turned people into numbers, and only justice has the power to give people back their names.”

According to Matviichuk, only a strategic approach to transitional justice in which all segments of society take part can ensure “a just peace – which is the only sustainable peace”.

“I’m not a specialist on the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” she said,” but what seems clear to me is that, at least partially, the problem with justice is caused by the attitude of the international community which says that we need peace, but not justice. They think that peace is much more important than justice. And still, after two world wars and colonial wars and all that horror, they don’t realise that justice is a prerequisite for peace”.

Belousov, the chief war crimes prosecutor, agreed that Ukraine should study the experiences of the countries that emerged from socialist Yugoslavia, so as not to “repeat the same mistakes”.

“What I’ve heard from colleagues in the Balkans is that no one has the right to forgive on behalf of victims,” he said. “Only victims can do that. And I believe that Ukraine will not be in a situation and be forced to forgive the enemy on behalf of victims, because that would be a ticking bomb for many years.”

Ever since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukrainian authorities have been working on a strategic approach to transitional justice.

Bosnia never adopted such a document, which would set out a systemic approach to issues of truth, missing persons, reparations and memorialisation.

This year, Ukraine abandoned work on its own Transitional Justice Strategy and fed elements of it into the Strategy for Reintegration of Occupied Territories.

Lunova worked on the reintegration strategy. She said it is still only a framework, and specific needs are yet to be elaborated.

Matviichuk said it was vital that Ukrainian authorities and society do everything they can to avoid a frozen conflict.

“I think our generation is now fighting for our future children,” she said.

Savchenko, the former peacekeeper in Bosnia, said he too wants peace, but a just one, for his daughter.

“I want mothers to welcome their children home and children to welcome their parents.”

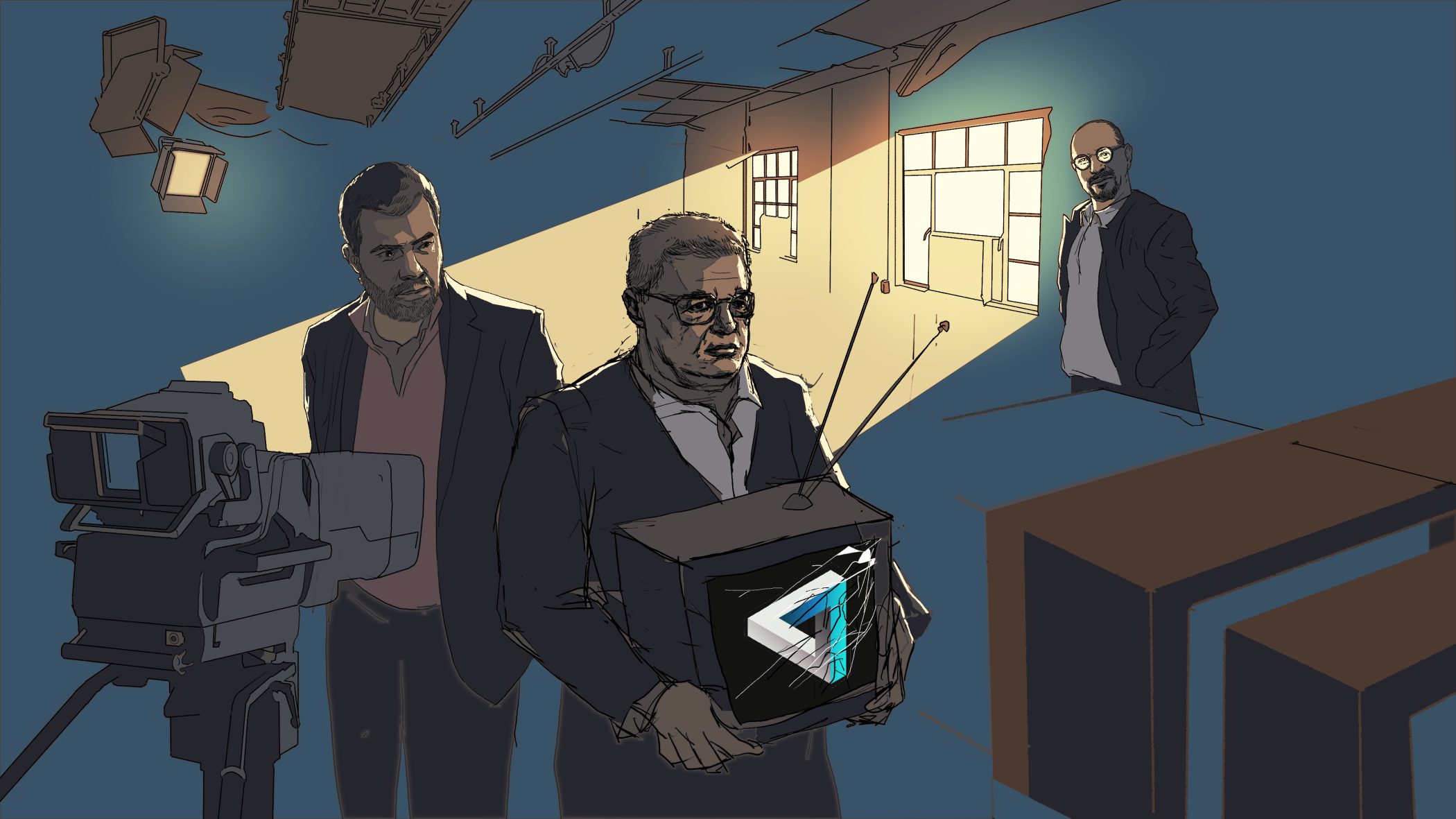

This article was compiled from material from the documentary ‘Pravda and Правда’, the title of which is a combination of the words ‘pravda’ (justice) in Bosnian and ‘правда’ (truth) in Ukrainian, which was released on the 20th anniversary of the founding of BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina on November 5.

The film was directed by Denis Dzidic and shot by BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina journalists Nino Bilajac and Enes Hodzic with Dzidic in Ukraine in the summer of 2024. Mirza Mokrovic was the film editor, Adnan Musanovic composed the music; Serhii Klymenko and Sergii Rozov were the camera operators in Ukraine, and Mirza Mrso and Anes Asotic in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The documentary is part of a project supported by the Federal Public Service for Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Belgium. As part of the project, BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Detektor team has compiled an overview of the most significant successes and failures in the transitional justice process in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the lessons that Ukraine can draw from them.

You can see all the content of this project on the subpage tranzicijskapravda.detektor.ba.