This post is also available in: Bosnian

It’s the T-shirt worn by one of the supporters captured in the picture giving a Nazi salute, printed with the slogan SH-MO, or Skinheads Mostar.

The rise of the Skinheads since 2012 reflects the tightening grip of far-right extremism on Mostar, a river town scarred by war and more recently by far-right, white supremacist and neo-Nazi graffiti.

Photo published in media and fan forums after the game between BiH and Ukraine.

In 2014 and 2015, as Russia fomented a separatist rebellion in the Donbass after annexing Crimea, between 20 and 30 Croatians are believed to have joined Azov, a battalion notorious for its neo-Nazi politics as much as its prowess on the battlefield against the pro-Russian rebels.

From the Balkans, Serb fighters sided with the rebels out of loyalty to Serbia’s fellow Orthodox ally Russia, while Croatian nationalists found common cause with the far-right elements of Ukraine’s resistance against Moscow.

Croatia, a country where conservative currents are strong and WWII revisionism is part of the political mainstream, has emerged as a key staging ground for the Ukrainian far-right’s international ambitions, according to the findings of a 2018 BIRN investigation.

And the links extend to Bosnia too, where a little over half a million ethnic Croats live. In Mostar, a town of some 100,000 people, they are the majority.

Devastated by the 1992-95 war, reconciliation and recovery in Mostar has been hampered by deep mistrust between Croats and Bosniaks.

Over recent years, the town has been blighted anew, this time by far-right graffiti, often accompanied by symbols and slogans of the HSK Zrinjski football fans.

Some of these fans have also made their way to Ukraine.

Post from a trip in Ukraine. Photo: Screenshot, Facebook

Logo “SH-MO”. Photo: Screenshot, Facebook

In 2017, on the eve of a World Cup qualifier between Ukraine and Croatia in Kyiv, Zrinjski fan and former player Ivan Ferenc posted a photo on social media, writing beneath it “The trip to white Croatia” and tagging himself as being in Ukraine.

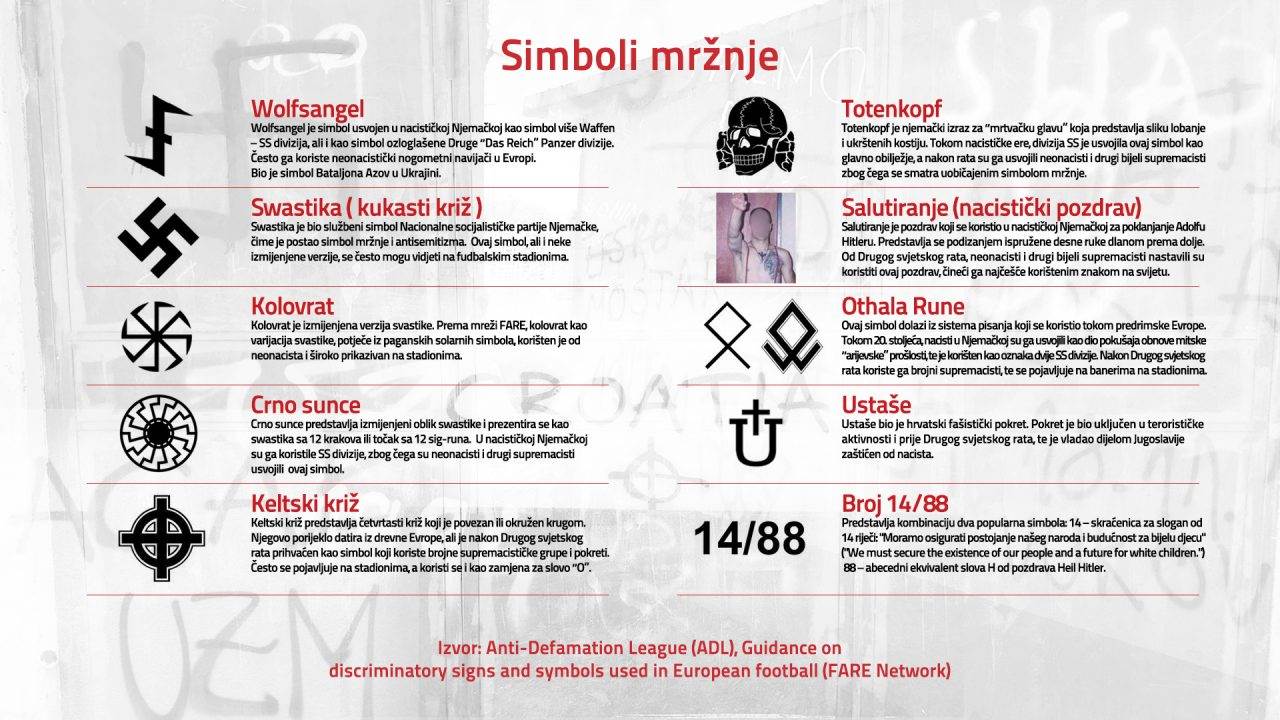

Ferenc posted more photos from a popular pub in the Ukrainian capital in which Azov symbols adorn the walls. One of them was the Wolfsangel, an ancient runic symbol appropriated by Nazi Germany and, decades later, by the far-right battalion.

“That is a very important symbol increasingly used in many countries,” said Professor Matthew Feldman, director of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Rights, CARR, and an expert on fascist ideology. “It is a well-known symbol of the far right.”

Poisonous ink

Skinheads Mostar has also used the Wolfsangel, as well as the slogan ‘Born to Hate’.

A review of social media activity by some of its members reveals a passion for tattoos, particularly featuring symbols associated with white supremacists and the paramilitary Nazi SS.

These include the Black Sun, the Totenkopf death’s head and the Celtic cross, photographs of which have been posted on social media by Mostar tattoo artist Davor Skobic, who travelled to Kyiv with Ferenc in 2017.

Feldman identified the tattoo symbols as either directly linked to Nazism or associated with “racist or neo-Nazi skinheads”.

Reached by phone, Skobic told BIRN it was up to his customers to choose their tattoos. Asked if he was a member of Skinheads Mostar, as would suggest by the ‘SH-MO’ symbol that featured on a T-shirt he wore in one of his pictures posted to social media, Skobic asked if the conversation could be continued at a later time.

“You should understand me, where I am, who I am,” he said.

A short time later, a woman called back and introduced herself as Skobic’s lawyer. She demanded that his photos not be published and that, if contacted again, Skobic would respond “in a far worse manner”.

Skobic’s far-right sympathies, however, are plain to see from his Facebook and Instagram posts, one of which features a picture of a child and the caption ‘14 Words’, shorthand for the popular white supremacist slogan “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children”.

The symbol 14/88 is scrawled on walls across Mostar, 88 denoting ‘Heil Hitler’, according to the New York-based Anti-Defamation League.

There is no ban in Bosnia on the displaying of neo-Nazi symbols, but provoking and fuelling racial hatred is a criminal offence punishable by jail.

HSK Zrinjski fined repeatedly for fan behaviour

Supporters of Zrinjski Mostar in Siroki Brijeg, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2019. Photo: EPA-EFE/FEHIM DEMIR

Ferenc’s Facebook photos include one of him standing in front of a goal with supporters displaying the slogan SH-MO. Contacted by BIRN, Ferenc declined to comment for this story.

In another of Ferenc’s photos featuring the SH-MO slogan is a former soldier of the Bosnian army, Dino Lovric. On his left hand, Lovric has a Black Sun tattoo, drawn – according to Facebook photos from 2017 – by Skobic while Lovric was still an active member of the army.

The Bosnian defence ministry told BIRN that Lovric served for seven years, ending in 2018 at his request. While previously researching far-right groups elsewhere in Bosnia, BIRN identified another former soldier who displayed his far-right sympathies.

BIRN contacted Lovric but he declined to comment.

Football terraces in the Balkans have long given voice to the region’s political and ethnic divisions.

“This trend is evident in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with fights between groups of Ultras, mostly divided along ethnic lines,” University of West London professor Alberto Testa wrote in a paper published this year on Ultras in Bosnia. “In a number of cases, however, violence has escalated, exacerbated by the legacy of conflict.” The paper cited HSK Zrinjski’s fierce rivalry with Velez, the Mostar side most popular with Bosniaks.

HSK Zrinjski, in a brief response for this story, dismissed the “stereotypes” about football fans being far-right.

But the behaviour of its supporters has cost the club heavily. Over the past five years, Bosnia’s Football Association has fined the club some 200,000 Bosnian marka, roughly 100,000 euros, for the flawed organisation of matches, the use of flares and fireworks by fans, political messages in the stands and the use of megaphones.

UEFA last year fined HSK Zrinjski 96,000 euros for, among other things, the improper conduct of its fans during qualifying matches for the Europa League.

‘They stand over the road, waiting’

Supporters of Zrinjski Mostar in Poland – Marko Vidovic (on the left with rised hand), Ivan Ferenc i Davor Skobic (on the right): Photo: Screenshot, Facebook

The official HSK Zrinjski Supporters Club declined to comment for this story or help BIRN approach any Zrinjski Ultras.

The only Ultra who agreed to speak was Vlado Savic, one of the original founders of the Supporters Club. “Zrinjski means everything to me,” he said.

Savic blamed the far-right graffiti that has scarred Mostar on outsiders.

“The guys in charge of graffiti have nothing to do with that,” he said. “People come from elsewhere and intentionally do that to defame us, make us look bad.”

But in his home, where he was under house arrest after being convicted of armed robbery, BIRN saw a photo of Savic and another man making what appears to be a Nazi salute. Similar photos on Facebook show Savic making the same salute. He denied it was a Nazi salute, saying it was simply a gesture Zrinjski supporters make when they sing the club song.

In the neighbourhood around Savic’s home, not far from the supporters’ club, far-right hate symbols are hard to miss, from the Celtic cross, a signature of the Zrinjski fans, to 14/88, swastikas and phrases declaring that the fascist WWII-era Independent State of Croatia, NDH, “will come again”.

The hate graffiti also adorns Mostar’s Partisan Cemetery, where Communist partisans who fought the Nazis during WWII are buried.

Every February 14, visitors to the cemetery mark the anniversary of the town’s liberation from fascism in 1945. In 2015, on the 70th anniversary, they were met with projectiles and insults hurled by a group of what one participant in the commemoration, Stefica Galic, described as “neo-Nazis.”

Authorities at the time said three people had been arrested, but that has not stopped such incidents from repeating every year, said Galic.

“They stand over the road, waiting,” she told BIRN. “Zrinjski supporters have some premises across the road from the Partisan Cemetery and they were already waiting there.”

The local interior ministry said those involved in the intimidation had been identified and prosecuted, but did not identify them when asked to do so by BIRN.

Michael Colborne contributed to this article from Kyiv, Ukraine.