This post is also available in: Bosnian

Soon after his appointment last month as director of Toplane, the public heating company in Sarajevo Canton, Enver Zornic found himself under fire. It didn’t take long for the local media, led by investigative outlet Zurnal, to reveal that the local government appointee had a prior conviction for involvement in civilian deaths during wartime.

The government, as well as the Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which proposed Zornic for the position, came under severe criticism from the opposition and the public. As a consequence, Zornic was ousted from the party and the appointing committee also resigned.

The incident, which gathered significant public attention in a country that is still in the midst of processing crimes committed during the 1992-95 war, was curious for one thing: although it was originally reported that Zornic had a war crime conviction, it turned out that he had actually been sentenced by the Sarajevo Regional Military Court for individual counts of murder instead.

Zornic, along with several other members of the wartime, Bosniak-led Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was found to have been responsible for the murders of two Serb civilians, Jagoda Jankovic and Sreten Ninkovic, as well as the killing of Josip Gogalo, a Bosnian Croat.

Jankovic, who was held in detention under Zornic’s supervision, was promised that she would be included in a prisoner exchange in the Sarajevo neighbourhood of Grbavica, but instead she was taken to an abandoned house, where she was shot in the head. The same thing happened to Ninkovic.

After Gogalo was taken for questioning and held for four days, he was promised release. Instead he was taken to the same abandoned house and shot several times in the head. All three bodies were then burned at the site.

The three murders were committed in cold blood, and although Zornic didn’t pull the trigger himself, the testimonies at the trial established his knowledge of the plans prior to the killings and his participation in the subsequent cover-up.

A facsimile of the 1993 sentence, provided to BIRN by the Cantonal Court in Sarajevo, which has inherited all of the Sarajevo Regional Military Court’s archives, shows that Zornic provided the petrol used to set the bodies on fire. The sentence details that Zornic was aware of the crimes that were committed, and that the perpetrators duly reported what they had done each time.

Zornic was found guilty of three counts of murder by command responsibility and the destruction of evidence, and sentenced to ten years and three months in prison. According to the archival documents shown to BIRN by the Cantonal Court, he served a total of three years in custody prior to the trial and after sentencing, between January 7, 1993, and December 30, 1995. He was pardoned not once but three times by the presidency of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But Zornic told BIRN that he still doesn’t think of himself as guilty and remains confused by his trial, claiming that he was just a civilian with no command authority.

“My guilt regarding Josip’s murder simply doesn’t exist, apart from the fact that I was simply there at the time. I was put on trial based on command responsibility, although I had no command function, and that’s the whole point. I was tried in front of a military tribunal, as a civilian, and I still have no idea how or why,” Zornic said.

The 1993 sentence shows that Zornic was a “member of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina from April 6, 1992” and “deputy commander in charge of security of the 6th Mountain Brigade”.

Biased justice during wartime

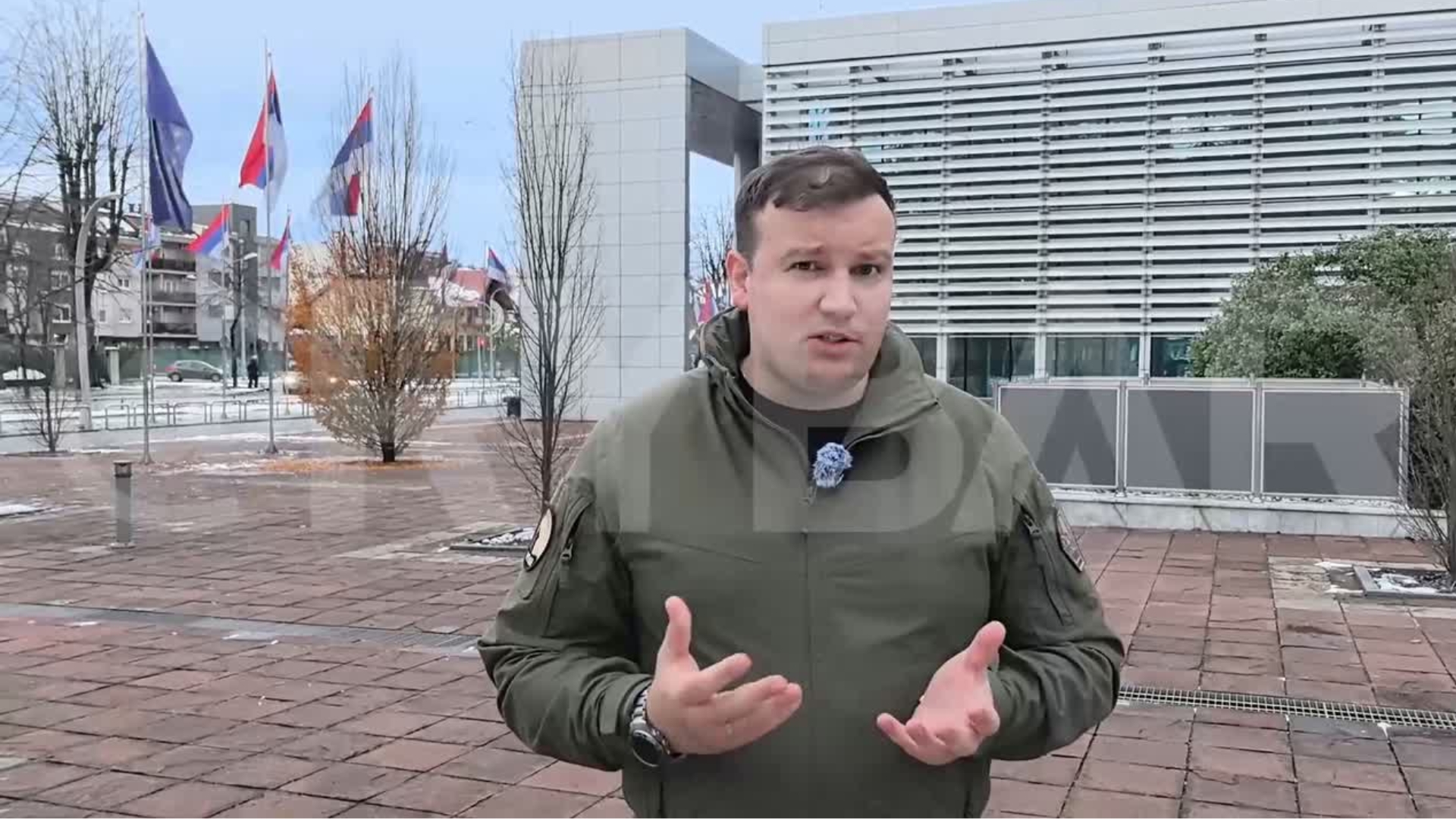

Enver Zornić. Izvor: N1/screenshot Youtube

Enver Zornić. Izvor: N1/screenshot Youtube

The total number of cases like Zornic’s that could have potentially been prosecuted as war crimes, but were instead processed as individual counts of murder, is unknown. The Cantonal Court in Sarajevo told BIRN that, given the size of the Regional Military Court’s archives and the way they are organised, it has “no way of searching” for data on similar cases.

Twenty-six years later, it is also difficult to determine the official reasons why Zornic’s case didn’t merit a war crimes charge. Mustafa Bisic, the military prosecutor who filed the indictment against Zornic and the others, told BIRN that he is “not responsible for giving statements and will not comment on anything about that”.

Nevertheless, the criminal law that was in use at the time, inherited from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, had a specific provision on war crimes against the civilian population. Article 142 said that those “breaking the rules of international law during wartime… ordering an attack on civilians (or) to conduct murders, torture, inhumane treatment of the civilian population” could be punished by a minimum of five years in prison, or even the death penalty.

Muhidin Kapo, who headed the jury at the 1993 trial, said he thought that the decision to prosecute the men for murder instead of war crimes was appropriate, and the sentences fair.

“We sentenced them, and they have served those sentences. They came out ‘clean’, or rather, as free citizens. People do things in war that they wouldn’t even think of doing during peacetime. As far as I know, that case was reviewed by the Hague and was rated as properly undertaken,” Kapo said.

But lawyer and former judge Vlado Adamovic said that the Zornic case not being qualified as a war crime was symptomatic of all such trials during wartime. The problem with this and other similar cases, Adamovic said, was that each side “prosecuted their own” and looked for ways to ensure that the sentence was milder.

“Unfortunately, that plagued the wartime period and wartime trials. We had cases that ended in probation, for actions in which the law didn’t allow for that , or cases which began and ended on the same day,” Adamovic told BIRN.

Zornic’s case is far from being the most well-known. The executions of non-Bosniaks and the disposal of their bodies at the Kazani ravine on Mount Trebevic near Sarajevo saw a number of members of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s 10th Mountain Brigade, under the command of Musan Topalovic, alias Caco, end up in court – but they were also tried for murder, not war crimes.

The number of people killed at Kazani during the siege of Sarajevo has never been officially determined. It was only after the war that the remains of 23 victims were exhumed during several excavations.

Historian Nicolas Moll, who wrote ‘Sarajevo’s Best-Known Public Secret’, a study analysing the crimes at Kazani and their consequences, told BIRN that his research clearly showed that “the prosecutor’s office was certainly aware that the crimes of Kazani were not on the level of murder”.

Media reports quoting original documents from the prosecution said that the indictment “was originally foreseen for war crimes, but was then converted to murder in the final indictment”, Moll said.

The reasons for this were not clear, but Moll said it would be fair to assume that “because of the politically explosive nature of the topic, the judicial authorities decided to amend the indictment, either by themselves or because of political pressure”.

With the war raging, the pressure on the Bosniak-led authorities in Sarajevo to keep a clean record was immense, as the Bosnian Serbs, Bosnian Croats, as well as neighbouring Serbia and Croatia, were all ready to jump on any chance to present all three sides as equally to blame for any legal violations.

‘Vile, systemic crimes’

Kazani iznad Sarajeva. Izvor: Facebook, “Neobilježena mjesta stradanja”

Kazani iznad Sarajeva. Izvor: Facebook, “Neobilježena mjesta stradanja”

Senad Avdic, editor-in-chief of the Sarajevo weekly magazine Slobodna Bosna, who followed the wartime cases, also believes that the Zornic case, as well as others, was marred by political interference in the work of the judiciary at the time.

“I think it was even clearer after the arrest and processing of members of the 10th Mountain Brigade in November 1993. Ten members of that unit, accused of the most vile, systemic crimes against civilians in Sarajevo, also weren’t tried for war crimes, but rather for ‘regular murders’,” Avdic said.

Avdic claimed that an anonymous source present at high-level meetings between Bosnian political leaders and members of the judiciary and the military after the Kazani arrests had told him that the general consensus was that any war crimes accusation would have been “damaging to the struggle ”.

The logic behind this, Avdic argued, was that any declaration that Bosnian Army members were war criminals “would have echoed in a very damaging way, both domestically and in the international community”.

Moll concurred that this was most likely the case: “If admitting that soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina had committed war crimes in Sarajevo, the Bosnian government would have blurred the clear message they wanted to transmit to the world during the war: there are the aggressors and perpetrators on the one side, and there are the heroic defenders and the innocent victims on the other side,” Moll explained.

“I suppose that there was the fear that had they admitted that soldiers of their own army have committed war crimes, would have blurred this clear distinction and given arguments to those in Serbia, in the Republika Srpska, within the international community, who wanted to put everybody on the same level of each side being guilty and each side equally committing crimes,” he added.

Avdic argued that a general conclusion, based on the facts that are available, would be that crimes by members of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the police during the siege of Sarajevo “were not committed in a planned and systematic way”.

“They were the actions of individuals and rebel groups. But their relativisation and even minimisation via the court processes was indeed systemic, and it came from the top level of Bosniak politics,” he said.

As for the question of whether the lack of political will or judicial courage should be seen as a negative mark on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s wartime history, Nicolas Moll said he believes that this is not a problem specific to the Balkan state.

“No government, no political group a priori likes to admit that there are also perpetrators in your own ranks, or, if it admits this, tries to downplay this,” Moll explained.

He argued that the story shows the courage of the Sarajevo media, which soon after the war’s end reported on the crimes and criticised the legal processes which saw suspects escape war crimes trials.

“Since 1997 already, there have been efforts by Dani and Oslobodjenje, and later also by others, to openly criticise this downplaying attitude, and to openly ask that the committed crimes are to be seen and qualified as war crimes,” Moll said.