This post is also available in: Bosnian

The UK suspected that almost 30 million Bosnian-made bullets sold to Saudi Arabia would end up in the wrong hands, but failed to warn Sarajevo before the shipment had flown, Balkan Investigative Reporting Network can reveal.

The deal was brought to the UK’s attention because two British-based brokers had requested – and were eventually refused – licences to mediate the Bosnia-Saudi deal.

Though Bosnian officials said it had no record of a broker being involved in the export, a BIRN investigation has established the shipment that left Bosnia in two parts in November 2015 and January 2016 with the approval of Sarajevo matched the deal for which the UK refused brokering licences in terms of timing, quantity, origin, destination and type of ammunition.

The UK refusal came in March 2016 after around 14 months of deliberation, when it was already too late to halt the shipment. Such applications are usually decided within 20 working days.

The refusal cited the “unacceptable risk” the bullets would be diverted, adding that the Saudi government, the specified ‘end user’, was not in fact “the intended recipient”, according to information obtained by BIRN under a Freedom of Information request submitted to the Department for International Trade.

Experts in the international arms trade say the UK likely suspected the bullets would end up in the hands of Saudi proxies in Syria or Yemen; even more worrying are the concerns raised by some watchdogs, including Amnesty International, about the leaky nature of US and Saudi arms pipelines into Syria, meaning some military hardware has found its way to extremists including ISIS.

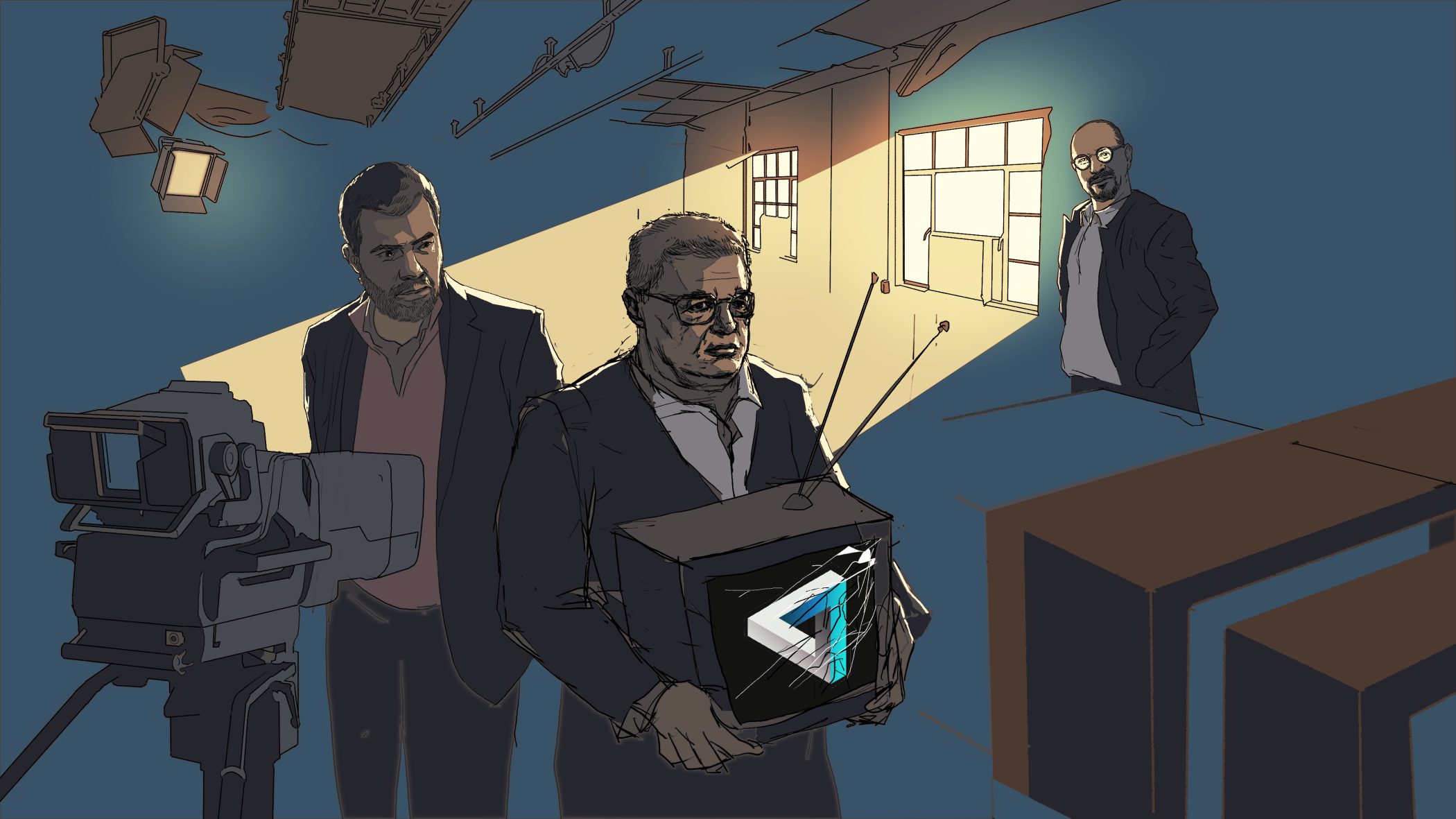

BIRN has reported extensively on the billion-euro arms trade that has developed between Balkan countries and Saudi Arabia, which systematically diverts the weapons to allied militias in Syria and Yemen.

Despite these concerns, and calls by the European Parliament to place an arms embargo on the Gulf kingdom, licences to Saudi Arabia are rarely rejected, making the UK’s decision all the more significant.

No obligation to share concerns

Balkan weapons and ammunition have been used in a number of Islamist attacks in Europe in recent years and Western governments count on countries such as Bosnia to crack down on arms trafficking, yet the UK made no apparent effort to warn Sarajevo of its concerns about this particular shipment.

A high-ranking Bosnian official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told BIRN that Sarajevo had received no communication from the UK on the issue.

The UK’s Department for International Trade said that given Bosnia is not a member of the European Union, there is no “established mechanism” through which the UK could have informed the Bosnian authorities.

The department declined to explain why it had taken so long to refuse the brokering licences for the shipment.

A spokesman for the department said: “The UK government takes its export control responsibilities very seriously and operates one of the most robust export control regimes in the world. We rigorously examine every application on a case-by-case basis against the Consolidated EU and National Arms Export Licensing Criteria, with risks around human rights abuses being a key part of that process.”

UK authorities refused to say who they believed would be the real recipient of the ammunition.

BIRN was unable to establish if the brokers applying for the UK licences were involved in any way in the Bosnian export.

Bosnia’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations said it had no record of a broker in paperwork submitted for the export licence – applied for by an unnamed exporter – and both London and Sarajevo declined to name those involved. Arms deals are notoriously opaque, the true actors often obscured by a chain of brokers and consultants sometimes in competition with one another.

Data BIRN has obtained reveal that the applications the UK refused, and those that Bosnia approved, matched in almost every other way. They were submitted at the same time in late 2014 and specified the exact same quantity and calibre of ammunition – including 13,492,927 AK-47 bullets and 3,063,276 rounds of sniper ammunition – split into three separate licences.

Unaware of the UK’s concerns, and unmoved by other evidence of Saudi Arabia’s diversion of arms to Syria and Yemen, Bosnia approved the licences in early 2015 and the goods were transferred to Saudi Arabia in November 2015 and January 2016.

Riyadh ordered bullets for AKs

Roy Isbister, an expert on arms trade laws with the London-based NGO Saferworld, said it “beggars belief” that London failed to share its suspicions with Sarajevo.

Asked why the UK might have refused the licence, Isbister told BIRN that the “most obvious explanation is that the UK would be fearing diversion to non-state actors that Saudi Arabia – and the US – is supporting in current Middle Eastern conflicts”.

Some of the bullets ordered by the Saudi authorities were not widely used by its forces, but extremely popular on the battlefields of Syria and Yemen. They included 15 million bullets for AK-47 style weapons.

Another 10 million 5.56×45mm bullets in the order are NATO standard and can be used by Saudi forces, but they are also compatible with Bulgarian AR-M9 rifles which were supplied to Yemeni soldiers by Saudi-ally UAE in 2015, according to weapons expert Jeremy Binnie from the London-based Jane’s Defence Weekly.

In mid-2015, a video surfaced that appeared to show ammunition airdropped by the Saudi-led military coalition in Yemen, including mortar shells clearly marked as made in a Serbian state-owned factory in 2012.

“Massive red flag”

The UK’s Department for International Trade said this was the first case involving Saudi Arabia that London had refused, having previously approved brokering licences for the export of similar ammunition from Bosnia to Saudi Arabia worth 10 million euros in 2013 and 2014.

Isbister said the refusal, based on suspicions over the Saudi end-user certificate, should serve as a “massive red flag for other potential exporters” including members of the EU and Balkan countries that want to join the bloc and which have been cashing in on Saudi Arabia’s sudden thirst for small arms and light weapons.

It may also complicate the UK’s lucrative defence trade ties with the Gulf kingdom, he said.

Last year, the UK successfully fought off a challenge in court by the Campaign Against the Arms Trade over its decision to approve sales of British arms to Riyadh despite allegations of war crimes in Yemen. The ruling is under appeal.

“The Government decided that Saudi assurances about what will happen to this ammunition are worthless,” said Isbister.

“And yet, in the ongoing court case into UK arms sales to Saudi Arabia, the Government has made it clear it places much more faith in Saudi claims of its own good conduct in the Yemen war than in the wall of information provided by respected impartial international human rights organisations and the UN to the contrary.”

Asked whether the UK’s refusal of the licences meant that Saudi Arabian end-user certificates could no longer be trusted, the UK government responded: “No, Saudi Arabia is a valued trading partner of the UK. An End User Certificate is only one element in the assessment of an export or brokering licence application: the provision of such a document is no guarantee that a licence would be granted.”

Sarajevo continues to export ammunition to Riyadh. In 2016, it approved 52 million euros of arms export licences for Saudi Arabia, according to the government’s yearly report of issued licences.

Bosnia’s Ministry of Foreign Trade told BIRN it was hardly alone in selling weapons to Riyadh. “A significant number of EU countries approve the export of goods from the Common List of Weapons and Military Equipment to Saudi Arabia.”

Contacted by phone, the Saudi ambassador to Sarajevo, Hani bin Abdullah bin Mohammed Mominah , asked BIRN to email its questions to the embassy. BIRN received no response to the emailed questions by the time of publication.

Serbian ammo “airdropped in Yemen”

In May 2015, several Yemeni news websites published footage and photos of materiel they claimed had been airdropped by the Saudi-led military coalition to its proxies in Yemen.

Pictures and videos, provided to BIRN by the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, clearly show ammunition boxes attached to parachutes. Markings on these boxes revealed their contents as 60 mm mortar shells produced in the state-owned Serbian factory Krusik in 2012.

Krusik said it had sold that particular lot to Zastava, another Serbian state-owned arms factory. Zastava and the Serbian ministry of trade did not respond to requests for comment.