JIGSAW PUZZLE

OF VERDICTS

Questions about the role played by Serbia and its military, police and political leaders in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina have been addressed in a series of court verdicts handed down by the Hague Tribunal and the International Court of Justice. The most conclusive judicially-established facts were presented earlier this year in the verdict in the trial of former Serbian State Security Service officials Jovica Stanisic and Franko Simatovic. Now that international prosecutions for war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina have ended, Detektor has analysed the differences between the verdicts delivered to see whether they confirm that the war was an international conflict, to understand the significance of the Stanisic and Simatovic judgment and to assess whether it will enable war victims and their families to sue for compensation in Serbia.

Only once has Berizeta Pitarevic has watched the entire video of members of the Scorpions paramilitary unit killing her brother Sidik Salkic and five other men from Srebrenica near Trnovo in July 1995.

“I entered the house, the TV was on. My mother was in the house when that video was shown in some news. She told me: ‘Ah, look at that man, looks like our Sidik.’ I said: ‘It’s not him’, and I quickly changed the channel. ‘Yes, yes, that’s his head,’ she said, but I did not let her watch it,” Pitarevic recalled.

She said wanted to cry, but she didn’t want her mother to see her and ask why. She watched the video in its entirety that evening, without her mother present, when the footage of the killing of her brother and the other men from Srebrenica was shown on the news.

“He was in a blue shirt, all covered with blood, his hands tied on the back, and when I saw that, that it was really him... I was screaming, they drove me to the [hospital] emergency room… I have never watched that video again, nor could I,” Pitarevic said.

In the years that followed, she tried as much as she could to prevent her mother from watching the murder of her son. She always kept the remote control close by, ready to switch channels if the video appeared. Each July she would take her mother to their house in Srebrenica, which had no electricity, because the footage was broadcast most often on TV during that period around the anniversary of the July 1995 Srebrenica genocide.

Today she believes that her mother did not see the July 1995 video while she was alive.

What she remembers about Srebrenica in the period before July 1995 is the shelling, lots of people arriving in the town, a lack of essential food supplies, electricity and water, as well as severe hunger.

“In my household, we did not put salt in bread for two-and-a-half years,” Pitarevic recalled. When the war started she was living in Srebrenica with her husband, but she later moved to the part of the town where her mother and brothers were living.

Later she returned to her family’s house, where 17 people were sharing one floor.

“We would cook [bread], but put no salt in it... The little salt that we had, we would keep for cooked dishes to at least make them edible with a little bit of salt,” Pitarevic said.

Seven days before the fall of Srebrenica, the town was shelled every day. On July 11, she headed towards the United Nations’ compound in the nearby village of Potocari together with her mother and her brothers’ wives and children, and left Srebrenica in the back of a truck.

She met her mother again in the town of Kladanj. Her mother hadn’t left Srebrenica with her because Bosnian Serb Army troops were holding onto her brother’s son and hit her sister-in-law who was trying to stop them from taking him away. Pitarevic’s mother recognised one of the soldiers and managed to save the boy.

As women, children and elderly people were moving towards Potocari, men, among whom were members of Pitarevic’s family, headed to the woods in order to try to reach territory controlled by the Bosnian Army. However, only her husband’s younger brother managed to get to Tuzla, while her two brothers, husband and his two brothers, uncles and other cousins did not.

Only years later did she hear that a video of murders of men from Srebrenica in Godinjske Bare, near Trnovo, had surfaced and was being broadcast on TV.

In the evening, when there was news... He was in a blue shirt, covered in blood, his hands were tied behind his back, and I, when I saw it, that he really was... I screamed, they took me to the emergency room... I never saw that video again reviewed, nor can I.

Vahida Delic saw her husband Juso last in mid-April 1992, when she left Srebrenica and eventually ended up in Germany, via Croatia and Slovenia. At the time, Delic was accompanied by her two-and-a-half-year-old child and she was pregnant with her second child. Her children only know their father from the footage showing his murder in Godinjske Bare.

Delic recalls a German television station broadcasting the video a few years ago and she did not recognise her husband, as she did not pay enough attention and did not watch the video to the end.

“I was at work and I came back home at around one o’clock. I always watched the news on TV. In the news, they showed six men lying on the ground, but that was all they broadcast, as it was a German TV station. I just turned my head away and said something like: ‘I pity the people who recognise someone there.’ However, their heads could not be seen as they were lying on the ground,” Delic said.

She received a message about the identification of her husband from his brother.

“My children only know their father from the video, from a picture, from the horrible video in which they watched him being killed, and I can tell you that my children’s health isn’t good either,” she said.

“My children only know their father from the video, from a picture, from the horrible video in which they watched him being killed, and I can tell you that my children’s health isn’t good either,” she said.

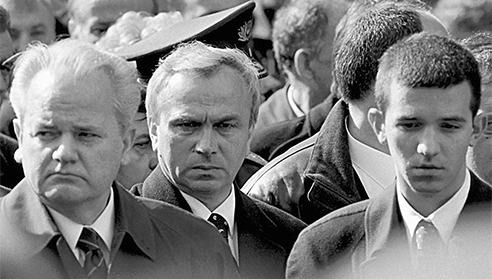

The footage of the murders committed by the Scorpions paramilitaries was first shown at the Hague Tribunal during the trial of former Serbian and Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic, who died before the verdict was handed down.

Four former Scorpions members, Slobodan Medic, Branislav Medic, Pero Petrasevic and Aleksandar Medic, were convicted in Serbia and sentenced to a total of 53 years in prison for the murders of the Srebrenica residents in Trnovo. Former Scorpions members Milorad Momic and Slobodan Davidovic were each sentenced to 15 years in prison in Croatia for the same crime.

The Serbian judgment convicting the former unit members states that the murders of the men from Srebrenica near Trnovo were committed during “the civil war in the then Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, fought between members of armed forces of Serbian, Croatian and Muslim ethnicity”.

The verdict’s explanation further states that it was a conflict between members of the peoples that lived in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and therefore was not international in character.

Jovica Stanisic and Franko Simatovic, the former leaders of the Serbian State Security Service (SDB), were also convicted of the murders of Srebrenica residents, but their final verdict at the Hague Tribunal does not deal with the character of the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first-instance verdict in their trial determined that an armed conflict existed in the territory of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which lasted throughout the period relevant to the crimes from the indictment, but it also stated that the parties reached a consensus that “an armed conflict” existed.

The last Hague Tribunal verdict for crimes in the former Yugoslavia was delivered in May 2023 in the trial of Stanisic and Simatovic, who were each sentenced to 15 years for involvement in a joint criminal enterprise in six municipalities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and at one location in Croatia.

Besides the fact it was the Hague Tribunal’s last verdict, it is also important for being the first final verdict to convict Serbian officials of crimes committed as members of a joint criminal enterprise, whose other members included, among others, former president of Serbia Slobodan Milosevic, Zeljko Raznatovic, alias Arkan, and the political and military leaders of Republika Srpska, who were convicted previously - Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladic, Momcilo Krajisnik and Biljana Plavsic.

The common goal shared by the members of the joint criminal enterprise was to forcibly and permanently remove the majority of non-Serb population from large areas in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina by committing criminal acts.

Stanisic and Simatovic were found guilty of bearing responsibility for deportations, forcible resettlement and persecution in Bijeljina, Zvornik, Bosanski Samac, Doboj and Sanski Most during 1992, as well as for the murders of six men from Srebrenica near Trnovo and the mass liquidation of civilians in the vicinity of Sanski Most in September 1995.

Under the first-instance verdict two years earlier, Stanisic and Simatovic had only been by of contributing to achieving the joint criminal enterprise’s common goal through organising the training of members of a paramilitary unit from Serbia and local Serb forces from Bosanski Samac. The fighters were trained at the Pajzos camp around the time that they took control over the Bosanski Samac municipality in April 1992, after which members of the trained unit committed crimes against the non-Serb population, including the murder of 16 civilians at a detention facility in Crkvina.

The second-instance chamber accepted the prosecution’s arguments, pronouncing Stanisic and Simatovic guilty of contributing to other crimes listed in the indictment.

It accepted the evidence that, from at least December 1994 and throughout 1995, the State Security Service headed by Stanisic and Simatovic paid daily subsistence allowances to members of the Serbian Volunteer Guard, in particular around the time of the murders in Sanski Most.

As stated in the verdict, the payments generally demonstrate systemic support to “activities of the Serbian Volunteer Guard, as an organisation”, and the Appeals Chamber determined that o reasonable doubt existed that Stanisic was not only aware of, but was also responsible for, such payments.

“The Appeals Chamber finds that the payments described above significantly contributed to the furtherance of the common criminal purpose and to the coordinated murder operations in Sanski Most – in particular the murders committed in Sasina and Trnova,” the verdict states.

The Hague Prosecution previously accused Zeljko Raznatovic, alias Arkan, of crimes in Trnova and Sasina, which were committed by members of a paramilitary group known as the Serbian Volunteer Guard or Arkan’s Tigers, but his trial never began and the proceedings against him were terminated after his murder in Belgrade.

The judgment in the trial of Stanisic and Simatovic states that the crimes committed by the Serbian Volunteer Guard and paramilitaries that worked in coordination with it in Bijeljina and Zvornik can be imputed to Raznatovic, a member of the joint criminal enterprise. It stated that the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) also participated in the attack on Zvornik, and was training and supplying weapons to paramilitaries.

The Appeals Chamber restated the adjudicated facts from the first-instance verdict in the Stanisic and Simatovic and cited evidence showing that, around the time of the crimes, Slobodan Milosevic exercised authority over the JNA and influenced decisions about operational arrangements, including the retention and transfer of personnel and arms.

“Consequently, the Appeals Chamber concludes that all reasonable doubt has been eliminated that crimes committed by the JNA, or forces working in coordination with it, during and after the takeover of Zvornik and prior to May 12, 1992, are attributable to Slobodan Milosevic, a joint criminal enterprise member,” the verdict states.

Similar claims about Milosevic as a member of the joint criminal enterprise are presented in the part of the verdict referring to crimes in Doboj committed during an attack on the town in May 1992 in which the JNA participated, in coordination with other Serb paramilitary units, as well as to crimes committed by the JNA together with other units in Sanski Most in April that year.

The crimes committed in Sanski Most in May 1992, as well as the murder of the six men from Srebrenica near Trnovo, which were committed by members of the Scorpions, were attributed by the Appeals Chamber to another member of the joint criminal enterprise – Ratko Mladic.

“Stanisic’s and Simatovic’s responsibility for crimes committed in Bijeljina, Zvornik, Doboj and Sanski Most in 1992, Trnovo, and in Daljska Planina in Croatia, is established by virtue of their membership in the joint criminal enterprise,” the verdict states.

It further states that they shared a common goal with other members of the joint criminal enterprise throughout the period of the commission of crimes in Sanski Most in September 1995, and previously in Bosanski Samac, through the organisation of training and deployment of forces during the takeover of the town.

Besides the members of the joint criminal enterprise, the verdict also names several commanders of military and paramilitary units who have either been prosecuted in previous years or against whom proceedings are still being conducted for crimes committed in the municipalities covered by the Stanisic and Simatovic verdict.

of Serbia’s wartime role

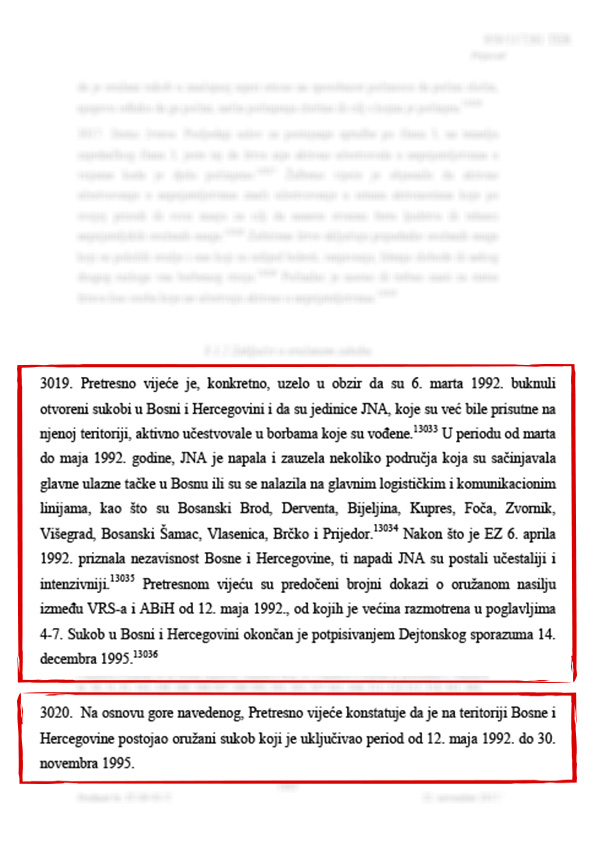

The first ever verdict handed down in The Hague in 1997 considered whether the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was a conflict of internal or international character, and drew conclusions to which other subsequent trial chambers adhered.

Although Hague verdicts primarily dealt with proving individual criminal responsibility for the crimes committed, they also stated that it was first necessary to prove that there was an armed conflict on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the relevant time and that defendant’s acts were committed in the context of that conflict.

Debates over the character of the war were presented in verdicts, noting the activities and participation of units of the JNA, particularly in the first months of the conflict, ie. prior to the establishment of the Bosnian Serb Army, VRS, but almost all decisions contained the fact that the international tribunal had the jurisdiction to prosecute crimes against humanity “when committed in armed conflict, whether international or internal in character”.

One of the initial first-instance verdicts, delivered in the case against Dusko Tadic for crimes committed in Prijedor, stated that, until May 19, 1992, a state of international armed conflict existed on at least part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mid-May 1992 was marked as the period when Serb military and paramilitary forces, according to the verdict, had the support of or were under the command of the JNA, which “formally” withdrew from Bosnia and Herzegovina at that time.

In the second-instance verdict, the Appeals Chamber concluded that, after the withdrawal of the JNA (Yugoslav People’s Army) from Bosnia and Herzegovina, the VRS (Bosnian Serb Army) was established to “continue to achieve the FRY’s (Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’s) own political and military goals”. The Appeals Chamber said that the first-instance verdict’s conclusion that the FRY and its army cooperated and coordinated activities with the VRS, rather than controlling the Bosnian Serb armed force overall, was not critically sound.

According to the Appeals Chamber, at least between 1992 and 1995, evidence suggests the FRY held overall political and military authority over Republika Srpska.

“The Appeals Chamber therefore concludes that, for the period material for this case (1992), the armed forces of the Republika Srpska were to be regarded as acting under the overall control of and on behalf of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). Hence, even after May 19, 1992 the armed conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina between the Bosnian Serbs and the central authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina must be classified as an international armed conflict,” states the Appeals Chamber’s verdict in the Tadic case.

The verdict for crimes committed at the Celebici detention camp, near Konjic, in the case against Mucic et al, said the war had the character of an international armed conflict that existed on the date of the recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina as an independent state.

It stated that JNA was actively involved in preparations for the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina by participating in the distribution of arms to Serb citizens, and that, after the declaration of independence, open conflicts broke out in which JNA units actively participated in combat.

“The Trial Chamber has no doubt that the international armed conflict taking place in Bosnia and Herzegovina at least from April 1992 continued throughout the year and that its nature did not change substantially. The withdrawal of JNA soldiers who did not have Bosnian citizenship, and the formation of VRS and VJ [Yugoslav Army] represented a deliberate attempt to mask the continued involvement of FRY in the conflict, with its government essentially remaining the driving force of Bosnian Serbs,” the first-instance verdict in the trial of Mucic et al states.

The Appeals Chamber in this case explains that the situation in which a state, the FRY, resorted to the indirect use of force against another state, Bosnia and Herzegovina, by supporting one of the parties involved in the conflict, the Bosnian Serb forces, may indeed be characterized as a proxy war of an international character. It further states that, in this context, the “overall control” test was utilized to ascertain the foreign intervention.

The chamber in the case against Radoslav Brdjanin later addressed the role of the Yugoslav Army, previously the JNA, ultimately finding in the verdict that “the armed conflict that took place in the Autonomous Region of Krajina (ARK) throughout the entire period of the Indictment was international in nature”.

The same chamber was convinced that the steps taken to create a VRS independent of the JNA were merely a ploy to fend off any potential accusations that the FRY was intervening in the armed conflict taking place on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina and to appease the requests of the international community to cease all involvement in the conflict, while support to the VRS was maintained.

“Despite the change of name from JNA to Army of the Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina after May 19, 1992, and subsequently to VRS, no consequential material changes actually occurred. While the change in the name did not point to any alteration of military objectives and strategy, the equipment, the officers in command, the infrastructures and the sources of supply also remained the same. In addition, the JNA military operations under the command of Belgrade that had already commenced by May 19, 1992 did not cease immediately and the same elements of the VJ [Yugoslav Army] continued to be directly involved in them,” states the verdict in the trial of Brdjanin, who was convicted of committing crimes in several Bosnian municipalities.

The definition of the character of the war was not elaborated upon very much in the verdict in the trial of Momcilo Perisic, former chief of the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army, who was initially sentenced to 27 years in prison and later, in the second-instance ruling, acquitted of charges of assisting in the commission of crimes in Sarajevo and Srebrenica. In the verdict, the chamber focused more on the way assistance was provided to the VRS from Serbia.

The first-instance verdict states that the VRS depended heavily on FRY and VJ assistance in order to function as an army and this dependence involved various forms of assistance, including logistics and personnel as well as support in communications.

The same verdict concludes that Perisic repeatedly exercised his authority to assist the VRS in waging war and that his actions substantially facilitated the commission of crimes “because the VRS heavily depended on the VJ’s support to function as an army and conduct its operations, including besieging Sarajevo and taking over Srebrenica”.

However, in the final verdict, the Appeals Chamber held that it had not proved beyond reasonable doubt that Perisic facilitated assistance that was specifically directed towards the VRS crimes in Sarajevo and Srebrenica, nor was the chamber convinced that the VJ aid which he facilitated had been proved to have been specifically directed towards crimes in those two cities.

In other Hague verdicts, the chambers usually concluded that, throughout the period in which criminal acts in the indictments took place, there was an armed conflict, and a link between that armed conflict and crimes committed. Some verdicts, which were limited to certain municipalities or broader regions only, found that the armed conflict existed only in those areas in the period relevant to the indictment. Some stated that the armed conflict ended with the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement in late 1995.

Individual verdicts clearly stated that the prosecution did not focus on proving the character of the conflict, which was considered “irrelevant”, as in the case against Stanislav Galic, who was sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against the population of Sarajevo. It was noted that the existence of an armed conflict between Bosnia and Herzegovina and its armed forces on one side and Republika Srpska and its armed forces on the other was not disputed, while the second-instance verdict in the trial of Dragomir Milosevic, who was also convicted of crimes in Sarajevo, stated that the Trial Chamber did not determine the character of the armed conflict to which the indictment referred.

Among the last judgments delivered in The Hague were those in the trials of former president of Republika Srpska Radovan Karadzic and former commander of the Main Headquarters of the VRS, Ratko Mladic, which noted, in terms of the character of the war, that an armed conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina or a widespread and systematic attack aimed at the Bosniak and Croat civilian population existed throughout the period relevant to the indictment.

The verdicts in the trials of Karadzic and Mladic name, among others, Momcilo Krajisnik, Biljana Plavsic, Nikola Koljevic, Mico Stanisic and others as participants in an overarching joint criminal enterprise, but they do not mention Serbian officials, who were named subsequently in the verdict in the trial of Stanisic and Simatovic.

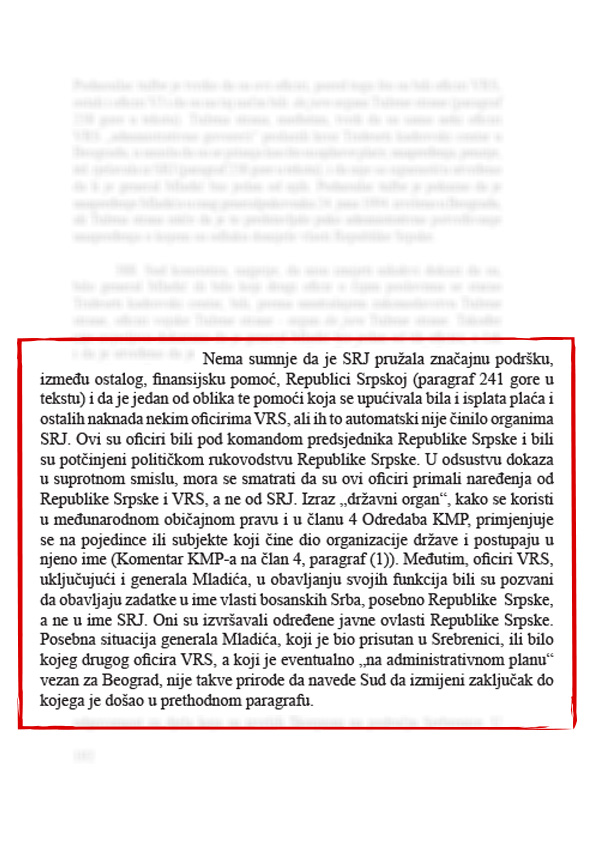

Unlike some Hague judgements, the judgment delivered by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on a lawsuit brought by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia assesses the role of the neighbouring state differently, particularly as regards cooperation between military bodies, noting that “the functions of the VRS officers were to act on behalf of the Bosnian Serb authorities, in particular the Republika Srpska, not on behalf of the FRY”, and saying that they exercised the public authority of Republika Srpska.

“There is no doubt that the FRY was providing substantial support, inter alia, financial support, to the Rеpublika Srpska, and that one of the forms that support took was payment of salaries and other benefits to some officers of the VRS, but this did not automatically make them organs of the FRY,” the chamber found in the ICJ’s verdict on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s lawsuit against Serbia in February 2007.

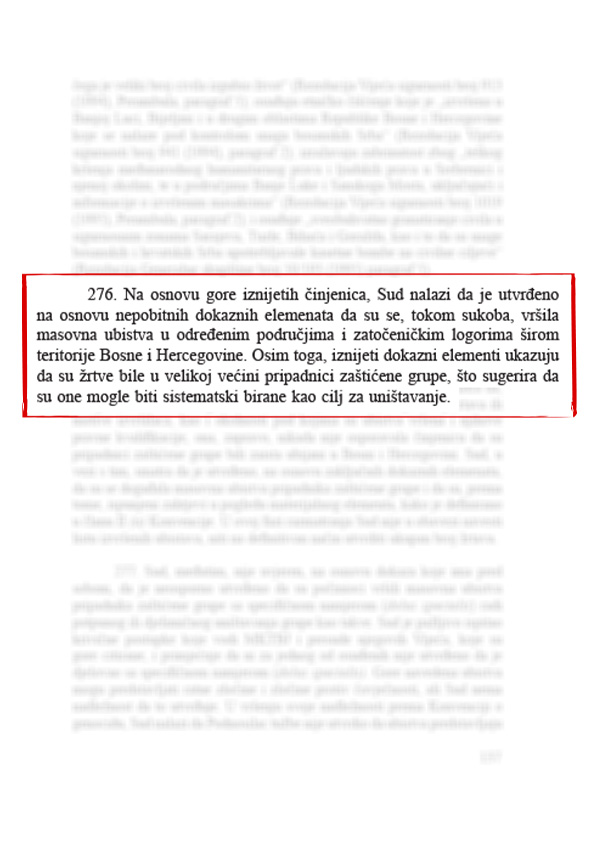

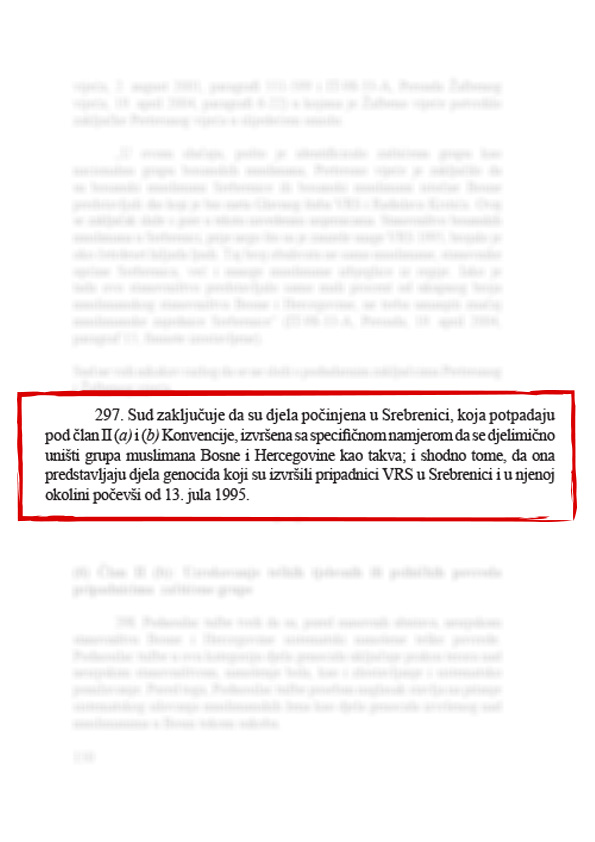

The same verdict states that during the conflict, mass murder was committed in certain areas and in detention camps throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that the atrocities in Srеbrеnica were committed with the specific intent to partially destroy a group of Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina and that they represented genocide committed by VRS members in Srebrenica and its surroundings.

It was also found that it has not been established that the massacres in Srеbrеnica were committed by people or entities classified as institutions of Serbia, nor that they were committed on Serbia’s instructions or under its direction, nor that the neighbouring state exercised effective control over the perpetrators.

But it was concluded that Serbia did not show that it took any initiative or action to prevent the atrocities being committed, and that its state institutions did nothing to prevent the Srеbrеnica massacres.

The ICJ verdict also examined whether Serbia could bear responsibility for the acts committed by Scorpions. But it was unable to determine that the Scorpions were an organ of the neighbouring state.

According to the ICJ verdict, the parties referred to the indictment in the Stanisic and Simatovic case, but the ICJ stated that it could not draw further conclusions as to the status of the Scorpions, in terms of whether the unit represented the Serbian Interior Ministry or not, as the case against the Serbian State Security chiefs remained at the indictment stage.

The final verdict in the trial of Stanisic and Simatovic states that the evidence corroborates that the Scorpions acted in coordination with the VRS in Trnovo.

Detektor’s analysis shows that the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, over more than 270 verdicts for war crimes, treated the question of the conflict differently. In verdicts, it uses the phrases “during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina” or “during the armed conflict” without defining the character of the war in more detail. Most court decisions state that the crimes were committed within a widespread and systematic attack by military and police formations against the civilian population.

The state court’s chambers accepted the facts established by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague, so they stated in verdicts that “an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between states or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organised armed groups, or between such groups within a state”, not denying the existence of a conflict between the armed forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska and their military and police formations.

Verdicts delivered by the Higher and Appeals Court in Belgrade, on the other hand, state that it was an armed conflict that was not international in character, or even that it was an internal conflict.

After the war crimes prosecutions concluded in The Hague with the verdict convicting Stanisic and Simatovic, legal experts consider it important that former Serbian officials have been convicted for crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and that they have been found guilty as members of a joint criminal enterprise.

Nenad Golcevski of the Humanitarian Law Centre said that crimes committed in Bijeljina, Zvornik, Bosanski Samac, Doboj, Sanski Most and Trnovo, as well as in Dalj Planina in Croatia, confirm Serbia’s connection to crimes, not only to the conflict itself, and demonstrate that Serbian state institutions were responsible for crimes committed by paramilitary units.

“Perhaps more important, the Appeals Chamber found that Stanisic and Simatovic, alongside other military, political and police heads from Serbia, but also from the so-called SAO Krajina, Slavonija, Baranja, Zapadni Srem and Republika Srpska, formed part of a joint criminal enterprise aimed at permanently removing the non-Serb population from territories controlled by Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. So it was about ethnic cleansing,” Golcevski said.

According to Golcevski, certain indictments link the state of Serbia with crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, but this link was confirmed by the verdict in the trial of Stanisic and Simatovic.

“The official narrative dating from the 1990s, according to which Serbia did not take part in the conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, has now been overturned completely. That is the key element of this verdict in terms of how the wars are assessed and perceived,” said Golcevski.

Klaus Hoffman, one of the prosecutors in the case against Stanisic and Simatovic, said in his personal capacity that Serbian State Security played a crucially important role in the wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and was heavily involved in the formation of Serbian units in both countries, and in the training, equipment, financing and coordination of those units.

“In my opinion, much of the war and many of the crimes would have not been possible without the support and contribution of Serbian State Security. It all followed the overall plan to create a ‘Greater Serbia’, which was shared by the two accused and other key players in Serbia,” Hoffman said.

He said that the evidence in the case did not focus on the nature of the armed conflict, but rather on the personal role and contributions of the two defendants with regard to the specific crimes in the indictment.

“The core challenge for the prosecution in this case was to show that both the accused were personally liable for these crimes, although no one ever alleged that either of the accused personally killed any of the civilian victims or committed any of the charged crimes on the ground,” Hoffman explained.

After Stanisic and Simatovic’s second-instance verdict was handed down, Serge Brammertz, chief prosecutor at the International Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals, said the prosecution was very satisfied with the verdict as one of the main reasons behind its appeal was to prove the defendants’ role in the joint criminal enterprise.

“The verdict showed that, according to our claims, it was not a civil war or some internal conflict within the borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but it was an international conflict which involved political leaderships of neighbouring countries, in this case – Belgrade,” Brammertz said.

The role of Serbian units in the war is of particular importance for Amir Omerspahic. He spent nearly six months in the Sljivovica detention camp in the Serbian municipality in Serbia after the Yugoslav Army captured a large group of refugee men after the fall of the Bosnian town of Zepa.

Omerspahic said that, if the possibility arises, he would join a claim against Serbia for damages, particularly after the conviction of former Serbian state officials Stanisic and Simatovic.

He recalled that in July 1995, people in Zepa knew what had happened in Srebrenica, because a few people managed to go from one enclave to the other, and that men became prey, being hunted by soldiers around the woods, and, after several days of hiding and crossing the River Drina, they were arrested by the regular Yugoslav Army on August 2.

“We figured out right away that we were not welcome. They killed a guy from Zepa in front of us. There was complete chaos. The military police came with dogs, forcing us to stand in line in twos, with our hands behind our neck and our heads down. We ran through that forest. I got a serious injury to my left fist,” Omerspahic recalled.

He said all the captives were “packed” into a truck and transported to a place called Sljivovica near Uzice, where they were handed over to regular police officers.

“At first I thought: ‘It will be easier for us, we got rid of the army.’ But then the real hell began. They accused us of war crimes right away. We all had some indictments, which we had to sign. The mental and physical abuse went on for 24 hours, as we were questioned and taken out of that room, and on our way back to the room we had to pass between two lines of policemen beating us all the time,” Omerspahic said.

He said that many Bosniaks were already in Sljivovica, and then buses started arriving and then driving some of the men from Zepa away to Mitrovo Polje, as they found out later. He believes that more than 800 people were held in the Sljivovica and Mitrovo Polje camps, living in bad conditions and sometimes not getting anything to eat for two days in a row. Omerspahic contracted gangrene during his detention. His finger was amputated in hospital.

From December 1995, the Serbians started releasing group by group of prisoners from Sljivovica. Omerspahic left on January 29, 1996, while some were held until May.

He is ready to get involved in a lawsuit for compensation for his suffering, because he saw how the detainees were held in a prison camp guarded by the police who were “armed to the teeth” and used various implements tools to beat the prisoners and various methods to interrogate and brutalise them.

“Collective lawsuits are the strongest. If we start with individual ones, I am sure it will not get us anywhere,” Omerspahic said.

He said that the former detainees had already filed a lawsuit in Serbia, but it was rejected by the court for reasons he did not specify.

Berizeta Pitarevic and Vahida Alic, whose brother and husband were killed near Trnovo in July 1995, also said they would join a lawsuit against Serbia for compensation should the possibility arise.

Nenad Golcevski of the Humanitarian Law Centre said that the Serbian law stipulates that victims and injured parties can file a claim for damages on the basis of a second-instance verdict by any domestic or Hague-based court, but only if the victims are named in the verdict.

The Appeals Chamber’s verdict in the case against Stanisic and Simatovic mentions the name of one victim only – Marija Senas from Dalj Planina in Croatia.

Golcevski said that the Serbian War Crimes Prosecution of Serbia should now respond to the facts about the role of Serbian units in war crimes that were established by the Hague verdicts and prosecute those responsible, because it no longer has a reason to not to act. He added that this was particularly important for perpetrators who live in Serbia, about whom there is abundant evidence, he argued.

“It is necessary to criminally prosecute other perpetrators before courts in Serbia and it is necessary for second-instance verdicts, containing the identity of victims established through those processes, to exist. The trial chamber’s verdicts in the Stanisic and Simatovic case already contain numerous facts about abuses, detentions, deportations, murders and other crimes against members of the non-Serb population in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. And that also includes the identity of victims,” said Golcevski.

In November, the European Commission published a report that said the pace of processing war crimes cases has significantly deteriorated in Serbia in recent years, and that there should be a genuine commitment to address war crime cases, including cases against of high-ranking suspects.

The European Commission said that this is also necessary because the country has a backlog of over 1,700 cases in the pre-investigation stage.

Chief Hague prosecutor Serge Brammertz has previously said that a number of war crime suspects are in former Yugoslav countries and there needs to be a lot more interaction between prosecutors’ offices to improve regional cooperation over war crime cases, which has so far been inadequate.

The European Commission report also condemned the frequent glorification of convicted war criminals and the provision of support to such individuals by senior state officials in Serbia, as well as the denial of verdicts handed down by international tribunals and the denial of the Srebrenica genocide, all without repercussions. The European Commission further criticised the fact that Serbia’s judiciary has failed to include financial compensation for war crime victims in criminal proceedings, even though the law provides for that.

Golcevski said that the Humanitarian Law Centre has represented victims in dozens of compensation cases, emphasising that the Centre is in contact with victims and will support any initiative for reparations or other forms of compensation for victims and victims’ families.

Omerspahic said that only establishing the truth matters to him and his fellow ex-prisoners.

“The material damages are no longer important for us, but determining that a detention camp existed there is important, because our goal now is for them to stop messing us around,” ,, he said.

The author: Haris Rovčanin

Videographer: Mirza Mršo

Assembly: Mirza Mokrović

Editor: Semir Mujkić

Deputy editor: Džana Brkanić

Director: Denis Džidić

Design: Zlatan Karadža

Project manager: Katarina Zrinjski

Photo: Detektor, EPA

Detektor, December 2023.