Gavrilo Stevic: ‘They Tried to Recruit Me into Fighting in Ukraine’

This post is also available in: Bosnian

Gavrilo Stevic was acquitted on March 10 of going to fight in Ukraine after being the first person to be prosecuted for such an offence in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Stevic spent a few weeks in Ukraine in 2014, but the Bosnian state court found that the state prosecution neither determined what exactly he did there nor proved that he belonged to Jovan Sevic paramilitary unit, which was predominantly composed of members from Serbia and Republika Srpska, according to verdicts handed down by Serbian courts and testimonies from witnesses in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The indictment charging Stevic alleged that he went to Ukraine with the help of a Chetnik ‘duke’ from Serbia, Bratislav Zivkovic, who was under an investigation in Serbia for having recruited and organized the departure of volunteers to the war-affected Ukrainian region of Donbas, but the investigation was eventually discontinued. Stevic told BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina in an interview that while he was in Ukraine, there was an attempt to convince him to fight for pro-Russian forces.

“They tried to recruit me, especially Bratislav Zivkovic, but I found a way out. I wanted to go there as a journalist, and then some compromises were found, I got by, I had freedom, I did not want to be under anyone’s command, to be used for their purposes,” Stevic said.

He explained that he used to meet Zivkovic in Rostov-on-Don in Russia and also in Luhansk in eastern Ukraine.

“He wanted to recruit me to become his soldier, but I didn’t want that. We had certain problems and our relations changed from favourable to bad, I simply did not want to be his soldier or under his command, I wanted to be free,” Stevic said, adding he did not “want to take part in the killings and the misery”.

Zivkovic has previously told BIRN that he “has known Gavrilo for a long time”.

“We used to meet at Ravna Gora and similar gatherings. Gavrilo was really engaged in writing and journalism in Luhansk, and he sang Serbian and Russian songs at gatherings a number of times,” Zivkovic said.

He said he did not distribute plane tickets to volunteers to travel to Russia on their way to Ukraine, but claimed this was done by the Chetnik movement.

“It is true that the Chetnik movement donated tickets to Serb Chetniks to travel to Russia as a form of assistance, hoping they would be able to earn money and pay for the tickets later,” Zivkovic said.

Besides his association with the Chetnik ‘duke’, Stevic appeared at some of the most important events in Ukraine and the Balkans linked with the activities of pro-Russian associations and individuals.

He told BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina that on July 17, 2014 he was in the Luhansk region when the MH17 Malaysian Airlines plane was shot down, killing all 283 people on board.

“I was occasionally with the armies. It happened that Serbs were injured and hospitalised, so I went there to interpret, as I speak Serbian. I was occasionally with the armies, I was more interested in Russian operations around Luhansk. As soon as we arrived in Luhansk, it was under a heavy artillery fire for nearly two months. The first ceasefire began when the Malaysian plane was shot down, so we could breathe, walk about and do other things for around seven days. As the war was starting, the armies did not conduct any other operations except for generating fear and causing people to flee using huge artillery potential on both sides,” Stevic said.

He said the city of Luhansk was frequently shelled, so he spent most of the time in a shelter near the monastery and obstetrics unit, which he said was also shelled.

“I could not go out for two, three or four days, we didn’t dare go out as the intensive shelling of Luhansk began at the time. It went on until I changed my location,” Stevic said, explaining that he spent the rest of his stay in Luhansk in the downtown area.

“I must tell the truth because of the Russian propaganda. The Ukrainians were trying not to shoot at civilian targets. They said churches were hit, children were killed, all sorts of things, but unlike here [in the Bosnian war], where there was unselective, insane firing, the Ukrainian army, tentatively speaking, was precise given the relative power of its weapons,” Stevic said.

He said while he was walking about in Luhansk during the seven-day truce, he did not see the Russian ‘Buk’ missile system which allegedly was used to bring down the Malaysian plane, and was subsequently photographed in the streets of Luhansk while withdrawing towards Russia.

“No, I did not see it. I was glad because it gave me an opportunity to walk, talk and, travel for seven days. By that time I had resolved my status, they allowed me to move freely, to depart. They did not let me be a journalist, they did not know how to treat me, so then they let me go wherever I wanted and do whatever I wanted,” Stevic said.

Dutch official investigators and numerous independent investigative media outlets, such as Bellingcat, believe that it was the ‘Buk’ Russian missile launcher, which was available to pro-Russian rebels in Luhansk, that shot down the plane that was flying from the Netherlands to Malaysia. Stevic considers these findings to be propaganda.

The investigators named Igor Strelkov, alias Girkin, a former Russian volunteer in Visegrad during the Bosnian war, as one of those responsible for issuing the order to shoot down the plane.

Stevic said he did not meet Strelkov in Luhansk.

“It was a turbulent time with generalised anarchy in Luhansk, four to five commands, four to five armies – the situation was chaotic. With the exception of the shelling, the war had not yet started. Ukrainians did not kill each other, Ukrainian soldiers would bring their wounded comrades to be saved by Russians, they lay next to each other, with a certain level of distrust, but they tolerated each other, they are much more humane than us, they did not want the war, people in that area where I stayed definitely did not want the war; the war was produced outside,” Stevic said.

As BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina has reported previously, another Russian volunteer in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Alexander Kravchenko, had meetings with Strelkov in Luhansk. Kravchenko can be seen on a photograph standing next to Stevic and Zivkovic. Stevic claims the photo was taken at a camp in Russia while he was preparing for a climbing expedition.

Another person whose name was mentioned during the plane crash investigation was the then leader of the rebels in Donbas, Alexander Borodai, who also leads the Union of Donbas Volunteers, which has thousands of members, some of whom come from the Balkans.

Stevic says he is not a member of the Union of Donbas Volunteers. However he was present when one of its leaders, Victor Zaplatin, another former volunteer in Bosnia and Herzegovina, established the Balkans Cossack Army in Kotor, Montenegro, in September 2016.

“I founded a Serbian-Russian friendship association in Banja Luka in 2006, so it was logical for me to be there as a prominent Russophile dealing with Russian issues, who was on hand for those visiting the area, helping with interpretation, socialising, just like Russians who were on hand for me during my stay in Russia,” Stevic said.

He said that “the Balkans Cossack Army represents the spreading of the Cossack movement to the Balkans”, but also that Cossacks have been present in Bosnia and Herzegovina for a long time.

“They have a stronghold in the Balkans too, they have it because of history, because the Cossacks orient themselves very positively towards the Serbian people, and they fight. They participated as volunteers in this area in the 1990s [war], so they either fought here or are emotionally attached to this region,” Stevic said.

Stevic was among the people who travelled to Montenegro with a man called Slavenko Kuzmanovic, who appeared as a prosecution witness at his trial. During his testimony before the state court, Kuzmanovic said that he also went to Ukraine, while newspaper articles with a photo of a commendation to him from the Union of Donbas Volunteers were included as evidence.

Kuzmanovic said in his testimony that Stevic told him during the journey to Montenegro that he was a member of the Jovan Sevic paramilitary unit in Ukraine, but the court said that Kuzmanovic had neither personally witnessed this nor had direct knowledge of it.

“Slavenko Kuzmanovic was our driver at that gathering. We attended the gathering. It was not just a gathering, but a monument was erected in honour of Saint Alexander [Nevsky] and Vuk Karadzic in Andrijevica and there were some other Russian-Montenegrin events and other cultural happenings. Amongst others, the Cossacks and the Night Wolves bikers’ club were present, alongside some prominent people, the Cossack Army of Serbia and even some church leaders,” Stevic said.

He claims he did not known Victor Zaplatin before this, and that he met him in Kotor and he knew he was “a prominent member and founder of the Balkans Cossack Army”. He said he believes Zaplatin has founded similar associations in other countries like Greece.

“I think he is the man dealing with that in the Balkans. I did not have a chance to talk to him apart from a brief introduction. I had an opportunity to observe things during the constitution of the Cossack Army. I think he was declared an ataman [Cossack leader] in Montenegro, I attended the ceremony. It was an interesting ceremony associated with history and deep tradition. I haven’t had a chance to familiarise myself further with his work besides watching the ceremony declaring him an ataman and founding the Russian Cossack Army of the Balkans,” Stevic said.

Members of the Night Wolves of Montenegro also attended the founding ceremony of the Balkans Cossack Army. Stevic said he does not know the members of Night Wolves in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“I think those guys have an unpleasant appearance, I think the bikers are associated with Russophile ideas because President Putin is a member of that club. So some well-off bikers gather and stay there in Russia, the Night Wolves travel across Russia, and I think they are involved in politics,” Stevic said.

At the trial he claimed his motive for going to Russia and Ukraine had not been to fight there. Defence witnesses described him as a writer who “wanted to reconcile the warring nation” and as a journalist who wanted to write about the conflict.

“I wanted to get a journalist’s accreditation [in Donbas]. I was rejected at the very beginning, they had a very negative stance towards journalists. Only those who forced the issue of war and psychosis were allowed to report,” Stevic said.

He said he wanted to work in Ukraine for Republika Srpska news agency SRNA and get accreditation that way, but this did not happen so he went to Ukraine without any professional affiliation.

“I went to Ukraine as an individual with people who travelled to the battlefront – civilians, soldiers and others. I stayed there on several occasions, in the city of Luhansk and other cities, I went to the frontier zone, I crossed over to Donetsk, not the big one [in Ukraine], but Donetsk in the Russian Federation. The city is adjacent to the Ukrainian border, which refugees streamed towards, seeking shelter in Russia from the danger and the artillery,” Stevic said.

The indictment charged him with having been assigned arms in Ukraine and joining a paramilitary unit which gave him a salary. In his interview with BIRN Bosnia and Herzegovina he said weapons were easily available to everybody in the part of Ukraine where he was.

“I was not assigned a gun. I had a gas pistol for my own safety while walking about Luhansk, as the situation was completely undefined during my stay in Luhansk. For instance, there were four Russian commands, three separate groups and four Cossack groups – the situation was chaotic. You could not tell who was in command or what was happening in the city. Later on when the armies were formed, I left the Luhansk region,” Stevic said.

He also insisted that he did not receive a salary. However, interviews that he gave right after returning from Ukraine and in the subsequent years differ significantly. In his earlier interviews, he mostly described the fighting and shelling, but later on he spoke more about himself as a writer.

“I gave interviews to Ukrainian media, Russian media, local media here, and I think that those interviews set the criminal prosecution in motion. That is when certain [intelligence] services approached me, they wanted me to give them data, but I wanted to avoid it at all costs,” he said.

“I was surprised by the indictment being filed three or four years later, as I had forgotten about it. I was surprised by the arrest, the search; it was very unpleasant, I got somewhat scared about what was happening,” he added.

During Stevic’s trial before the state court witnesses described what he did in Ukraine and who he stayed with there. Stevic insisted that while in Ukraine, he did not meet Slavenko Kuzmanovic, who testified against him.

“I did not meet him. According to my findings, Slavenko was there much later, so I did not meet him. There were some Serbs, in addition to those living there, there were some Serb volunteers. A number of people wanted to come from Serbia, but {Serbian President Aleksandar] Vucic’s politics and Serbia impeded them. Perhaps there were some people from Bosnia and Herzegovina, but I don’t remember,” he said.

“While I was there I kept a diary and there is a lot of interest in it. The diary is in Moscow at present, they seized it so it would not be discovered who was there, and how and where they lived,” he added.

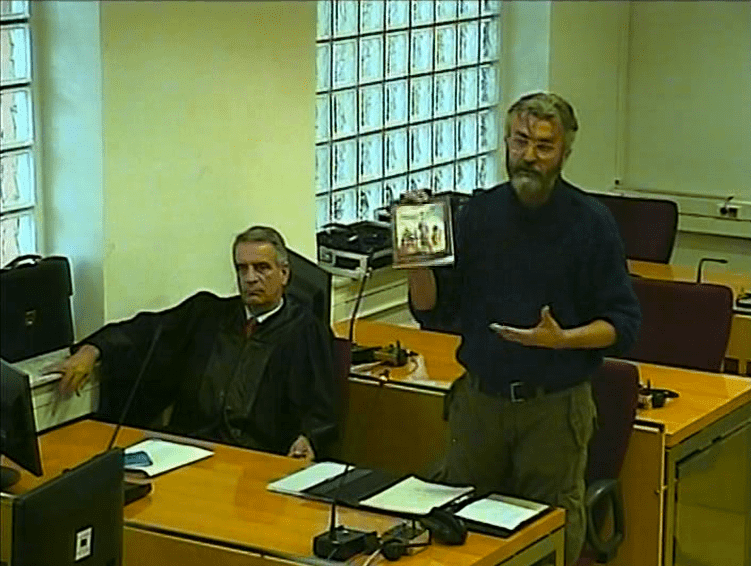

During the trial, a photo of Stevic holding a gun in front of a military truck with an ‘LNR’ (Luhansk People’s Republic) sign on it was shown several times in the courtroom. An expert witness interpreted the sign as the Luhansk National Republic. He says he was not in uniform in the photo.

“If you take a closer look, you will see I did not wear any military insignia or anything. With regards to the photo of me with a gun, there were some photos on a Russian webpage, I think the photo originated from a Russian camp,” Stevic said.

He said the Russian camp was a military one where refugees and soldiers were based.

“So, as is the case with most armies that are being established, both civilian and military institutions were at those camps, I think they were set up by private military companies since they were most organised and had money. Russia acts through private companies, private security companies, so it can dissociate itself from the state’s direct participation in the war. They imitate what the Americans are doing in the West,” Stevic said.

“I want to say I am nothing like the person they are portraying me as. People wanted to portray me as a cruel guy who wanted war, but I am an extremely anti-war-oriented person, although I consider that people’s freedom and rights of people must sometimes be defended with arms,” Stevic said.

The state court has handed down final verdicts sentencing 25 people to a total of 47 years and two months in prison in 16 cases for going to the Syrian battlefront or attempting to go there, and for recruiting others. Those who were convicted were given between one and seven years in prison.

The first-instance verdict acquitting Stevic can be appealed.